|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

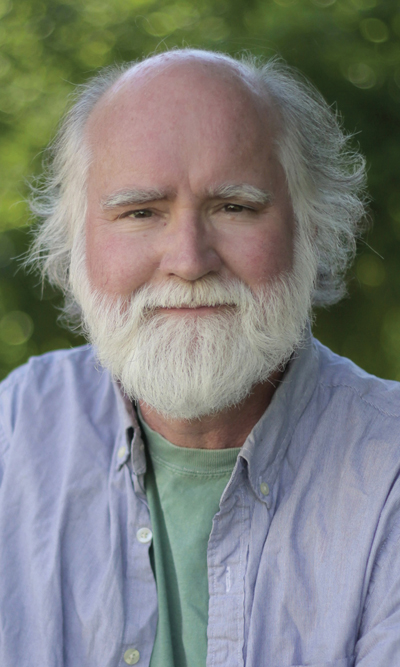

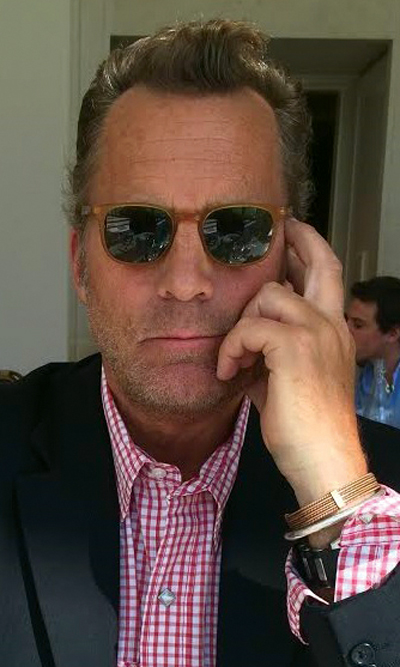

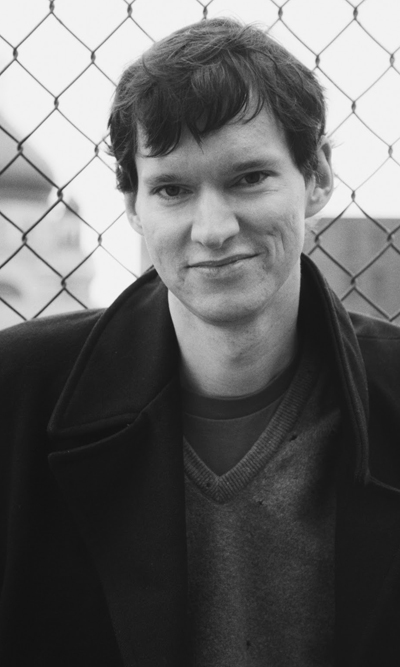

There’s a stand-up comedy bit from the late Bill Hicks where he’s sitting in some 1980s Waffle House in somewhere America, reading a book when the waitress asks him, “What you readin’ for?” Hicks is taken aback. He’s never been asked what he read for, only what he was reading. After some consideration, Hicks says, “You stumped me. I guess I read for a lot of reasons.” It’s a question worth considering: Why read? To be smarter, more informed? To be cultured, more well-rounded? To simply be entertained, thrilled? Yes. Yes. And yes. There might be, conceivably, a million answers to the question, “What you readin’ for?” Whatever the reason, those who read will find the answer to that question at the 14th annual Arkansas Literary Festival, running this Thursday through Sunday at locations around Little Rock. And those who don’t read? Well, the festival is a good starting point for a well-worth-it hobby. And the mostly free festival is not all about books. There are events for everyone, from Lego to lingerie. Click the images or names above for five interviews with authors who will be in attendance at the Arkansas Literary Festival, a project of the Central Arkansas Library System. A full schedule is available at www.arkansasliteraryfestival.org. NICHOLSON BAKERNicholson Baker writes “all over the place.” Sometimes in restaurants; sometimes in the car. All that writing has resulted in more than a dozen works of fiction and nonfiction, including Human Smoke: The Beginnings of World War II, the End of Civilization and House of Holes, and appearances in The Atlantic and The New Yorker. A winner of the National Book Critics Circle Award for 2001’s Double Fold: Libraries and the Assault on Paper, Baker is currently working on a nonfiction book “about old, old, old secrets. Old Cold War secrets.” His latest is Substitute: Going to School with a Thousand Kids, where Baker spent 28 days substituting in Maine public schools. Baker is at the Central Arkansas Library System’s Ron Robinson Theater on Saturday at 11:30 a.m. On writing every day “I don’t think I really started to figure out how to write until after I started writing every day. Occasionally I’m sick or I only write a tortured email — and there are times when I’m only rewriting, but essentially I try to do it every single day. The days I’m not expecting anything to happen are sometimes the days when the prose really picks up. And sometimes on the days when I get up in the morning, and say, ‘This is the day I really figure it all out,’ it doesn’t go as well. It’s a question of showing up at the keyboard.” On fluidly moving among different genres of writing “It doesn’t feel all that fluid as I’m doing it. It’s just a desire to get on to whatever the next subset of experience that is clamoring to be described. Sometimes it feels terribly important to come up with a story, kind of an escape somehow — to get that river bed texture of lived life down on the page. Sometimes it feels important to write something that’s a more traditional nonfiction kind of account, maybe to right some wrong. I’ve always got a backlog of things that I wish I could pull myself together and finish. Finishing is so hard. It never gets easier. The research part is a joy. But putting notes into a final shape, and having to leave out things along the way, that’s the really hard work. That’s where I struggle.” On listening to music while he writes “It helps to play trance, dance music. Gigantic thumping shopping bags of sound. For a while I listened to a lot of Paul Oakenfold, Kaskade, Deadmau5, Massive Attack — and really loud. I go through phases. Sometimes I like Brahms piano variations, sometimes it’s Chaka Khan. Lately I’ve been writing regularly to a composer named Aes Dana. Music is an amazingly efficient way of changing your mood, changing the flavor of one’s concentration. Sometimes, on the other hand, you need things to be, not just silent, but hyper silent. I’ll put in earplugs and then put on a pair of heavy, cushion-y headphones so that I’m enclosed in a sensory deprivation cocoon of silence. It depends on the kind of writing I’m doing. The book that I finished most recently, which is about being a substitute teacher, was a new experience for me because it was a book that came out of genuine cacophony. Kids are talkers, and classes of 22 kids are ridiculously noisy. I had to convey the chaos and confusion of what was going on in class in this completely silent medium of words in a book. That was kind of a new challenge.” On what he learned while substitute teaching “The only way for us to make progress with educational policy is to feel how difficult it is to make it through a school day. It’s an endurance problem for kids and for teachers. Both groups are shouting their throats raw and trying to survive and avoid burnout. The learning that happens is almost incidental to all of the other crazy — sometimes beautiful and funny and touching — things that happen in classrooms. And sometimes really tragic things. My idea was to write a book that took you, the reader, into this snow globe of confusion and made you hear the shiny unexpected phrases that kids were just tossing into the air, and understand how they’re trying to joke themselves into a state of alertness when they’re exhausted. The moral is: Listen to what kids want to tell you and learn from it. Start from the fact that we don’t necessarily need to make school more rigorous. Actually, we want it less rigorous, and a shorter day I think would be one of the best things we could possibly do for the student population of this country. Less is more.” On whether he heard any criticism about his book “I think some people thought: What on Earth is this man doing implying that he has things to offer on the topic of American education when he’s only been in the trenches for a semester — 28 days in a semester? Real teachers do this every single day. And what they’re doing is much harder than what I was doing. I could work for a couple of days, and then when I needed a break I could take time off. The way a substitute’s day works is a person calls at 5:30 in the morning and says, ‘You want to teach second grade?’ I’m staring at my pillow and I think: ‘Well, sure, OK.’ That’s how it works. I can say no. A real teacher can’t say no. I think there was some justified uncertainty about my standing. What I was hoping to do was to say, here, swim through this with me, folks, and see if you think differently about school afterwards.” On whether he still substitute teaches “I really miss it. If I had more time, I would be substituting a couple of days a week right now. I can’t because I have to make a living as a writer and I have a book to finish. There is something thrilling about being needed by a school district. They didn’t need me to be a trained, certified teacher. They just needed me to be a human being who was physically present and who was going to do his best to be a reasonably nice person and help students out here and there. That sense of being needed by the outside world is a great feeling and I miss it. I would say to anybody who was thinking about trying it: Don’t worry about what people say — that being a substitute teacher is a heartbreaking and horrendous experience. It is, it is. But it will teach you about human possibilities and about the possibilities of speech, of kids’ speech, that you won’t learn any other way.” On working on a keyboard versus longhand “I love to type — love that nimble-fingered feeling. I supported myself by typing other people’s writing back in the day when you could do that. I worked for corporate offices and legal firms in the ‘80s, and I typed all kinds of contracts, memos, financial reports. There were days when I was just typing numbers at a bank. There’s a pleasure in typing fast, and in going quickly through a document to fix typos. These days I often like to talk and type at the same time, with my eyes closed, so it’s sort of as if I’m dictating to my fingertips — speak typing. That avoids the step of having to transcribe later. I get odd looks when I do it in public.” C.B. MCKENZIEIt’s challenging condensing a half-hour conversation with C.B. McKenzie onto the page — the native Texan is a bit of a wild card, he’ll admit. But the author is never, ever boring. Having worked as a house painter, international model, professor, lifeguard, waiter and more, the Arkansas Tech University graduate is the author of two novels. His first, 2014’s Bad Country, won the Hillerman Prize for best debut mystery set in the Southwest and was a finalist for the Edgar Award for best first novel. His second novel, 2016’s Burn What Will Burn, is set in Arkansas. McKenzie appears at the Cox Creative Center at 4 p.m. Saturday. On Burn What Will Burn “I probably started it in the ’80s when I went to Arkansas Tech. My first wife and I lived out in the country, out in Dover. Right off of [Arkansas] 7, in the boonies. This was kind of my community. I mean it wasn’t as bad as that. … It’s a beautiful place. That’s the second book and it’s not even really a mystery. It’s like a mystery with no mystery to it, I guess. It’s a novel. It’s crime-driven. I mean, it’s a crime novel but it’s not really driven by the crime. The crime’s just kind of in it. That’s a totally different thing even from the first one. They are both noirish.” On how his diverse background has influenced his writing “It hasn’t. Is your idea the old-school idea that writers are people who have experienced a lot in their lives and then that informs their writing? That’s sort of the old Hemingway idea, that you go to Spain, fight in the war, join the merchant marines, you don’t get a real job, you pick apples in Washington, you work with the migrants, you move to New York City become a male prostitute or whatever. But people like Jonathan Franzen haven’t done any of those things. They are just writers. They just write. Novels is what they do. They don’t really have a lot of life experiences. I find their novels like that. … If you’re going to write an international thriller, it helps that you worked for the CIA. … I’m a strange person. Does that inform my writing? Well, it informs everything. It informs the way I eat cereal. I’m just a writer. I’m just a novelist. They come in all shapes and sizes.” On the book he is currently working on, The Same but White “It’s kind of like a Ruth Rendell or P.D. James. They are really my models for this book. An Agatha Christie, but with a little more character development. P.D. James and Ruth Rendell were really kind of later golden age women writers who wrote character-driven but also plot-driven mysteries; classic mystery novels that didn’t have a lot of sex in them and not a lot of cursing. So that is this book, which is very different than my first two books. Totally different. In fact, this one is sort of like Nordic noir. … It’s supposed to be a commercial book. If it doesn’t go, I’ll probably quit writing. I have one more book under contract, so I have to do something.” On the relationship between author and editor “Let me put it this way: I had a really bad year last year. I ... divorced [my wife]. My dad died. My mentor from college and dear friend of mine died. My favorite aunt had cancer. My mom moved into a nursing home. What else happened to me? I broke a finger. And the actual worst thing that happened was losing my editor. I got another one.” On how he creates his characters, like Bob Reynolds in Burn What Will Burn “He’s just me. That’s me in 1984. I actually wrote this book, it’s my MFA thesis from 2000. When Bad Country came out, it did pretty well. It didn’t do great. It got on the prize lists and got a good buzz, and my editor at the time really liked it and liked the way that I wrote. He really respected my talent and admired my inventiveness. That’s really what I do. I make things up. A lot of writers don’t. I think a lot of people write reflective fiction and they don’t make anything up except maybe a little twist at the end, but basically they just write their lives. Bob Reynolds — that’s my house. It had chickens on the front porch at one point and time. Who lived in the house before my first wife and I lived there was pit bulls. They used the house to kennel pit bulls. This is the real deal. Little Piney Creek, if you ever go outside of Dover, is right there. You’ll recognize it. When I took my next future ex-wife to the area and we drove around, she said, ‘This is exactly what’s in the book.’ And I go, ‘Yup.’ When you asked if my past informed my writing, the settings definitely do. All I did was dump a body into this creek and then try to figure out what would happen to me if I was living alone in this house with just my chickens, and there was a beautiful woman — a crazy, stripper type woman — and this kind of evil doctor. I just kind of made that up. A lot of writers are semi-functional in the world. Our genius, if we have a genius, our minor genius or just our talent, is just that we see the world in a little bit peculiar way. You have to be able to do that. … Where do my ideas come from? Well, I wanted to write a mystery about the death of somebody who wrote my own book. So essentially I made myself a victim.” On the writing process “I can write in my sleep, but it’s not fun. I don’t enjoy writing. I’m not Stephen King. Stephen King apparently just wakes up every day and just sits in his little office … indulges his fantasies and publishes anything he likes. And he’s great. I envy him. To me, writing is hard work. It’s not fun. Being a writer in the world might be fun if you are really popular but I’m not. People ask, ‘Why don’t you do a follow-up to Rodeo [from Bad Country]?' Obviously it’s set up to be a series. I say, ‘Because y’all bought 15,000 copies and not a 150,000.’” DORIT RABINYANIsraeli author Dorit Rabinyan’s latest novel is All the Rivers, a romance between an Israeli woman and a Palestinian man that was excluded from a list of required reading for Hebrew high school literature classes by the Israeli Ministry of Education. Published in 2014 as Borderlife, the novel won the Bernstein Prize for young writers, an Israeli award for Hebrew literature. The English translation of the novel is being released Tuesday. A native of Kefar Saba, Israel, Rabinyan’s previous novels are Persian Brides and Strand of a Thousand Pearls. Rabinyan appears at the CALS Main Library’s Darragh Center at 11:30 a.m. Saturday. On the idea for All the Rivers “I do believe that every fiction work has to have a spark imported from life or you wouldn’t be able to convince yourself in what you’re writing, nevertheless the reader. … The book evolves from an experience of a year I spent in New York and a group of Palestinian intellectuals and scholars and artists that I met there in Brooklyn. One of them was very special to me.” On her reaction to the Israeli Ministry of Education’s decision on All the Rivers “I was more than surprised. I was overwhelmed. This is the first time ever a book was banned from our curriculum for high school or for anything. We consider ourselves a democracy, and I consider myself a product of democracy so I wasn’t expecting anything like this to happen. Everyone who cared about freedom of speech was overwhelmed and protested.” On why the book was banned “The minister of education found it to be dangerous to the Jewish identity of the people that they might find it to be encouraging for getting involved in a romantic relationship with a non-Jewish resident. It’s so unbelievably ironic and not typically of Israelis I know of. … This is something we relate to totalitarian regimes; this is not what Israel is recognized for, or acknowledged herself for, and more like those regimes that we neighbor with. On the one hand it’s really a source of worry. And on the other hand it can be uplifting and look at it and see that it had aroused a huge debate around freedom of speech. So the democratic structure of Israel is stable enough to reject this from happening and maybe overcome it.” On how involved she was in the translation of All the Rivers from Hebrew to English “We [Jessica Cohen] were working together for more than a year back and forth because she lived in Denver. She is originally Israeli, brought up in the U.K. and then moved to the States. She has been translating Hebrew literature for more than a decade. She worked with one of our major authors, David Grossman, and her work was very recommended by him. So I was reassured by that. I didn’t need to question her queries or maybe her choices. We were corresponding by email. I have my books translated into 20 languages, and the only language I can really enjoy it in is English. I don’t know Korean. I don’t know French enough. I don’t know German to doubt anything. I was reading it and re-reading it and it was rewritten and revised, and we were having comments from the editor in the U.K. and the editor in America. She had done a great deal. She’s my partner. … She was the one to make it both understandable and literary, to be lyrical and musical. If there was some humorous aspect or some association that needed to transform from one language to another, it was hers to do. It’s not an easy job. It’s not rewarded in the culture that they do have such a huge mission translating literary works from one language to another. They should be much more appreciated. Hebrew is such a small language; it’s read by so few so I really consider her to be my partner.” ROB SHEFFIELDOhio was really the first state in the country to get into David Bowie and is filled with excellent ’70s Bowie stories — that’s just one fact Rob Sheffield knows about Ohio and Bowie, though he probably knows a few thousand more about Bowie, considering he wrote 2016’s On Bowie. A music, TV and pop culture critic at Rolling Stone since 1997, Sheffield is the author of several books, including Love Is a Mix Tape: Life and Loss, One Song at a Time; and Talking to Girls About Duran Duran: One Young Man’s Quest for True Love and a Cooler Haircut. His newest is Dreaming the Beatles: The Love Story of One Band and the Whole World, which is being released Tuesday. Sheffield appears at 4 p.m. Saturday at the CALS Ron Robinson Theater. On the genesis of Dreaming the Beatles “I’m really fascinated that The Beatles really belong to today in a way that is really rare for any music. There’s no sense that they belong to the past. It’s funny when you see little kids listening to The Beatles. Over Christmas, I was visiting my nieces and nephews and my nephew had just built the Lego Yellow Submarine. It’s so universal. My nieces can play guitar because of Taylor Swift. They played ‘Blackbird.’ To them, music is Katy Perry and Beyonce and Taylor Swift and The Beatles. There’s no sense of The Beatles belonging to the past or belonging to ancient history.” On what Beatles song speaks to him right now “Like you probably, I’ll answer that question different every day. One that I’ve really been feeling lately is ‘Strawberry Fields Forever.’ I’ve been listening to that song a lot and thinking how much I loved that song when I was 12 years old. I think about it now, and think, ‘How did I have any idea what was going on in that song?’ There’s so much melancholy in it, and he’s singing from the perspective of a guy who’s an adult and who’s remembering childhood and none of the problems he hoped would be solved are solved and he’s just weary and exhausted and very isolated feeling. I think, ‘Gosh,’ when I was 12 years old what did I know about any of that stuff? How was I supposed to hear myself in that song and it was really weird that I did.” On when he knows an idea arises to a book project “For me, the connections between artists are so interesting. Some of them, like Bowie and The Beatles have such long running and complex engagements with music from every generation and every culture and every personality type. It’s funny, artists who can sustain a whole book are artists who change over time and who are willing to change not just their music but also the way they relate to audiences. Like, I love Bob Dylan. He’s somebody that I am as obsessed with as I am with Bowie and The Beatles. But Bob Dylan is not really interested in changing his music. You could never picture him doing a record with Kanye West or Rihanna. Neil Young is an extreme example that way. I love those guys, but The Beatles, even though they broke up nearly 50 years ago, their music keeps changing and people keep finding new ways to hear it and to keep it alive. That’s really fascinating to me. It’s not something that belongs to the past.” On who his favorite Beatle is “When I was growing up in the ’80s, everybody had the same favorite Beatle and it was John [Lennon] because he was the cool one. And Paul, since he was putting out so many solo records and some were really cheesy, was the least-cool Beatle. But he was the one I kind of adopted as my contrarian, surly teen favorite. To me, Paul is this really weird, fascinating, complex guy who is so much more complex than people notice. I saw him last summer when he was on tour, in Washington, D.C., in a hockey rink and he played for three hours. I think he did like 40 songs and he ended with side two of Abbey Road, playing that all the way through. I thought, ‘Everybody would have been happy with so much less. What drives him to work this hard every night? Why does he love being Paul McCartney so much and putting so much of himself into it?’ It is kind of astonishing when you think about it. Nobody else his age has to work that hard. It’s amazing.” On his Rolling Stone David Bowie obituary, the spark that led to On Bowie “At the time [Bowie] died, I was in the middle of writing this Beatles’ book. David Bowie died on a Sunday night, and I stayed up all night writing about him and I sent my obituary in at dawn, but then I just kept on writing. Around 9 o’clock, my [book] editor called and she said, ‘What if we put The Beatles book on hold just for a few months, and you just do a David Bowie book, and we could do it for this summer?’” On being a Boston native and why The Cars are not in the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame “I vote for The Cars every time they are on the ballot. I voted for them the past two years. I think it’s insane they are not in the hall of fame. Partly I think it’s because they kind of epitomize a band that literally everybody likes. Literally everybody likes The Cars. At the time they were huge, music was so divided. There were hard rock fans over here. There were disco fans over here. And there were New Wave fans over here. But everybody could agree on The Cars. For me, I think it’s crazy they are not in the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame. And they will be; it’s just a matter of time. … They made at least three albums that are flat-out perfect.” On who else he thinks should be in the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame “The No. 1, the titanic one, is Chic. Another band that I loved when I was a little kid, and in terms of how influential they were and how inventive they were and making complex records — I think of them as the funk version of Steely Dan — that sounded smooth on the surface but incredibly complex and tricky and very musicianly. They had so many hits and I think they are not in the hall of fame because people think of them as simple hit-makers. They were a lot more than that. I vote for The J. Geils Band every time. I voted for Yes a few times; I’m glad they finally made it in. I vote for Chaka Khan. I’m just a insane Chaka Khan fan. That doesn’t necessarily make a historical or critical case. I’m just such a fan. People love to argue over who is or isn’t in the hall of fame, but they can only let in five or six bands at at time so mathematically they are never going to catch up. That’s part of what’s beautiful. One band that has never been on the ballot is Roxy Music. That, to me, is like Kraftwerk, which, I get it, they’re a German art rock band, not everybody’s cup of tea, to say the least. But Roxy Music, in terms of how hugely influential they were on so many different kinds of music and how great those records sound, I just worship them. I look forward to them getting in.” MICHAEL FARRIS SMITHIt’s early April and Mississippi author Michael Farris Smith is heading toward the Mississippi River, where he’ll stay in a cabin and finish revisions on his forthcoming novel The Fighter, which will be released in April 2018. Smith, whose writing has been compared to Ron Rash, Cormac McCarthy and Larry Brown, talks from Lemuria Books in Jackson, Miss., which lies about 150 miles southwest of his Columbus, Miss., home and where Smith teaches creative writing at Mississippi University for Women. The 2014 winner of the Mississippi Author Award for Fiction and native Mississippian, Smith’s works include The Hands of Strangers, Rivers and his newest, the February release Desperation Road. Smith appears at the CALS Ron Robinson Theater at 2:30 p.m. Saturday. On the idea for Desperation Road starting with the image of mother and daughter Maben and Annelee walking down the interstate “It was an image that wouldn’t let go of me. I was immediately worried about them. I felt compassion for them. Empathy. Sympathy. And I was curious, too, about why they were there. When something grabs you like that, I’ve learned you need to harness yourself to it and see where it takes you. I think some of that had to do with me being the father of two girls. It would be one thing for [the mother] to be walking down the side of the interstate by herself carrying a garbage bag, but when you put a child in her other hand, it really raises the stakes quite a bit. That was an image I really couldn’t get rid of so I just began to follow them and go with them and see what their story was.” On how much of himself is in Russell Gaines from Desperation Road or Cohen from Rivers “I think the biggest thing I have in common with both of those characters is probably just the sense of displacement they both have. I wandered around for most of my 20s, not really knowing where I was going or what I was doing, and that included living [in Europe] for a while and just really becoming detached, both geographically and I guess emotionally from people who I knew and things that I knew. When I did finally come back I was about 28 or 29 and that’s when I kind of decided that I wanted to start writing. … I felt that kind of emotional isolation I think, or just kind of feeling that you’re on an island a little bit. I think both Russell and Cohen both have that in common. Things change while you’re gone. I left Mississippi when I was about 22 and didn’t come back for seven or eight years, and things changed while I was gone and relationships changed. The biggest thing was that I changed. When I left, I was completely clueless and pretty worthless to be honest. I came back with a very clear goal in mind and that was kind of the first time in my life that I had really figured out what I wanted to do and that was to try to write fiction. There’s no way to explain how you come to that decision, but when I came back to Mississippi finally, I came back very different, very focused. I was different emotionally. I was just ready to stick my neck out there and see if it was possible.” On the influence the late Mississippi writer Larry Brown had on him “During my time abroad, I’d be back in Mississippi for a month or two, and I happened to be hanging out in Oxford during one of my breaks and I wandered over to Square Books and I picked up two books off the Mississippi writers table and that was Big Bad Love by Larry Brown, the story collection, and Ray, the novella, by Barry Hannah. I’d been reading Faulkner and the big names because I didn’t really know anybody. I’d been reading Hemingway and Fitzgerald and Dickens and Faulkner. I liked reading Faulkner. I didn’t always get it, but it gave me a connection to home. But when I picked up Big Bad Love and those stories by Brown, I … remember it just punched me in the gut. This is what a contemporary Mississippi writer was writing about. I knew the people in his stories. I knew the small town atmosphere. I just really felt a connection to it. A year or two later, when I decided to come back and write, a lot of that had to do with I’d read some interviews by him by then about his own experience of being 29 and deciding to see if he could become a writer. That was the same age I was, and I was really of the same attitude. It really gave me some encouragement that one, I wasn’t strange in doing this, and two, it might actually be possible if you work hard enough. That’s always been his influence on me. His influence has always been his fiction, but it’s also been the things he had to say about his own experiences that I found a lot of similarity with that has really driven me.” On his writing office in Columbus “About three years ago, after our second daughter was born, I just couldn’t write at home anymore, man, I had to get out of the house. I was fortunate enough to find a space in downtown Columbus that’s just a big empty room with a couple of windows, a table and a chair and a coffeemaker and a laptop. That’s where I go. That’s kind of my sanctuary. It’s my place to go and make up my stories and nothing else. My normal routine when I am going good is we get up in the morning and I take my daughters to school and drop them off a little bit before 8 o’clock and I go right to my space right then, and I’ll work from about 8 to 9:30 or 10. I try to do this Monday through Friday. I have to get it done before the day gets rolling. There’s something about the early morning where things are still kind of quiet in the world and I can sit and focus on what I’m doing.” On whether he works from an outline or not “I know people do it different ways, but the thing I enjoy about it the most is really the not knowing. I’ll write in morning and then I’ll make myself a couple of notes about what I think is coming next so that when I walk in the next day I have an idea of what’s up. I don’t like to look too far ahead. I’m always afraid I’m going to take my characters’ free will away if I plot too far ahead. I want them to be able to discover for themselves. I want to be able to discover as a writer. I like those days when I’m surprised. I like those days when I go in and I have an idea of what I think I want to do, and the day is over and I’ve done something completely different where I just kind of followed my instinct at the moment. It’s always way better than what my plan was for the day. What I hope is that the notion of discovery for me is the notion of discovery for the characters, and eventually it transfers itself to the reader and they feel that kind of notion of being unsure of what’s coming next.” |

||||