The kidnapper still clutched his 9 mm Luger in a lifeless hand.

A few feet from his body, in the rear of his rented silver minivan, his victim lay on her back, her wrists and ankles chained tightly to the four corners of the van's floor.

He had been hiding in storage unit No. 313 since the night before.

Throughout the day, he had cranked the engine and run the heater to warm himself.

As he had listened to the radio news reports about 13-year-old Kacie Woody's abduction of the night before, he learned that police knew his name and were looking for the minivan.

The engine was still running, the radio playing, when Conway police Sgt. Jim Barrett had approached the unit and raised the door.

That's when David Fuller shot himself in the head.

When Barrett and other investigators entered the unit more than three hours later, they found Fuller at the back of the unit, a few feet from the rear of the minivan, dozens of cigarette butts, a lighter and a bottle of Mountain Valley Spring water littering the concrete floor near his feet.

Fuller, 47, had backed the silver Dodge Caravan into the unit at Guardsmart Storage after snatching Kacie from her home in rural Holland. At some point, Fuller had removed the vehicle's two back seats to make room for his victim.

The seats now rested on the floor. One was folded. The other, on which Fuller had been sitting when he pulled the trigger, remained upright.

Fuller had been looking directly into the back of the minivan, where Kacie lay. He had raped her. And he had shot her in the head.

The final hours of the drama had begun a little after 5 p.m., Dec. 4, 2002, 19 hours after the abduction, when Barrett had heard the gunshot and summoned the SWAT team.

The lawmen had spent more than three hours in the sleet and snow waiting, unsure whether Kacie and her kidnapper were dead or alive.

Just before 8:30 p.m., the SWAT team entered the unit with Barrett close behind.

The detective identified Fuller, using the dead man's California driver's license. Then he looked in the minivan, and the image of Kacie there would haunt him for months each night when he put his own daughter to bed.

As investigators searched the unit, they found a half-empty bottle of chloroform and a purple rag next to Kacie's head.

Later, after police had studied the medical examiner's report, they would conclude that Kacie likely had been unconscious from the time she was kidnapped until she was killed, a small comfort amid the ruin.

According to a security box at the storage facility, Fuller had punched in his access code at 10:15 p.m., Dec. 3, which meant he had driven straight there from the Woodys' home in rural Faulkner County after abducting Kacie from her living room.

No one who worked on the case would ever agree on the time of Kacie's death. With the chloroform, she could have remained alive but unconscious for hours. Detectives don't know if she was dead or alive when Fuller left the unit on foot at 7:24 the following morning to buy water and cigarettes at a nearby convenience store.

The security box showed Fuller was gone 21 minutes.

He spent the rest of the day chain-smoking and, police speculated, waiting to flee the unit on foot after dark.

As investigators examined the crime scene, several lawmen gathered for a somber discussion : Who was going to notify Greenbrier police officer Rick Woody of his daughter's death?

Faulkner County sheriff's investigator Jim Wooley and state police investigator Karl Byrd volunteered. They had worked this case from the outset, and they would see it through.

DEC. 4, LATE EVENING

Jessica Tanner, 12, and several of Kacie's other closest friends were keeping vigil at 13-year-old Samantha Mann's house. By now, the local TV news broadcasts were reporting that police had cornered a man named David Fuller. Reporters described his rented minivan, and Fuller's face appeared on the screen.

Sam and Jessica looked at each other and spoke in unison :

"It's Dave."

Dave, whom Kacie had befriended on the Internet, had claimed to be 18. The picture on his Yahoo profile was of a goodlooking young man with long, wavy hair.

Sam stared, disbelieving, at this new version of Dave. He was balding and had a mustache. "He's ugly," Sam said. "And old."

And then there was an update : Authorities had stormed the storage unit. A news conference was scheduled for 10 p.m. The briefing opened with the first report of Kacie's death. Sam and her friends huddled on the staircase and wept.

At 12-year-old Haley Allen's house, the phone rang. The caller was her father, checking on her. Haley and Kacie had been friends since kindergarten.

"Are you doing OK?" he asked.

"Hopefully, they'll find her," Haley replied.

"You don't know?" There was an uncomfortable silence. Then Haley's dad said, "Let me talk to your mom."

Before she took the receiver, Leah Compton sent Haley to bed.

Haley obeyed reluctantly. For the next hour, she lay there, staring at the ceiling, wondering.

Finally, Leah and Haley's stepdad entered her bedroom.

Haley asked, "Is she going to be at school tomorrow?" "No," Leah said softly. "She's gone."

Haley cried and cried. And then, as many other kids in Greenbrier did that night, she crawled into bed with her parents.

Over on Griggers Lane, a handful of people had gathered at the home of Teresa Paul, Kacie's aunt.

Teresa, the older sister of Kacie's late mother, had moved next door to the Woodys in 1990, a few years after her husband, a native Alaskan, had drowned in the Yukon.

Teresa didn't say so, but she knew Kacie was never coming back. When she had returned from Rick's house at 6 a.m., she had seen an owl perched on the deck. In her husband's clan, the owl was the symbol of death.

She was prepared when a family friend arrived at her front door.

Teresa spoke first. "She's gone, isn't she?" Like Rick, Teresa had lost her spouse. And she, too, had lost a daughter. Her oldest girl, Jonna, died in a car accident in 1994. She was only 17. Heartbreak was an old, familiar acquaintance.

Teresa turned to her elderly parents, Chuck and Illa Smith.

"Mother," Teresa said gently, "it's over."

"Oh, they got Kacie?" Illa asked, hope lighting her face.

"He killed her," Teresa said flatly.

There was a stunned pause. And then the Smiths sobbed. First their granddaughter Jonna. Then their daughter Kristie.

Now Kacie.

Chuck turned to Teresa: "Why can't we keep our girls?" he asked. "We keep losing our girls."

Down the road from Teresa's house, dozens of people filled Rick Woody's home. Rick slumped in his recliner, watching the TV for updates on the standoff between the SWAT team and the man who had kidnapped his daughter. Rick also listened to the chatter on his police radio.

But as a TV news crew announced that there would be a news conference at 10 p.m., Rick's radio went silent.

And he knew.

ALPHARETTA, GA.

In this affluent suburb of Atlanta, 14-year-old Scott was telling his parents that something horrible had happened to a girl he had met on the Internet. It was some time after 9 p.m., EST, and Scott, known online as Tazz2999, had just learned from Internet news reports that Kacie was dead.

His parents, Steve and Pamela, were baffled. Who, they asked, is Kacie? And all of this is going on where? In Arkansas?

So Scott explained everything, starting with how he had met Kacie in a chat room in May 2002 and how she had disappeared the night before while chatting with him on the computer.

"This is not small stuff," Pamela told her son. "This is either a really sick joke, or it's something so terribly sad."

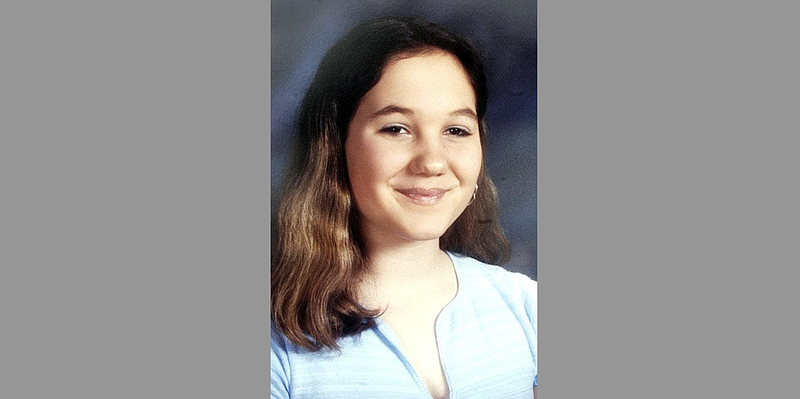

She looked at Scott's pictures of Kacie. There was a school portrait, a formal photo of Kacie in all her finery as Fall Festival Queen and a few candid shots from Kacie's webcam.

It would be several days before Pamela grasped the magnitude of what her son had gotten himself into - a murder case involving a girl from Arkansas, a killer from California and, eventually, a coastto-coast FBI investigation.

Pamela hadn't even known that Tazz2999 had a girlfriend.

DEC. 5, 2002

School counselor Dianna Kellar's office at Greenbrier Middle School was filled with crying students.

Flowers, stuffed animals and other teen paraphernalia soon covered locker No. 427, where Kacie had once gossiped with friends as she stashed her books.

Throughout the afternoon, teachers comforted sobbing girls and tried to soothe fears. By the end of the day, an oppressive grief had sucked the laughter and chatter from the halls.

THE GIRLS SAY GOODBYE

On Dec. 8, the night before Kacie's funeral, her friends arrived at the visitation with yellow roses and a group picture of themselves making goofy faces.

Sam tucked the photo under Kacie's pillow.

Then the girls took their roses, which had handwritten notes attached to each stem, and placed them one by one in the coffin. Except for Haley. She couldn't look at her friend. She gave her rose to Rick.

Kacie was wearing a yellow dress her grandma had made. It was a little tight on her, but it had been her favorite. Her Aunt Teresa had made sure two matching jackets went into the casket. She knew Kacie would want to show them to her mama in heaven.

During visitation, Rick said to Sam and Jessica: "Don't quit coming around. You're my girls too now."

OVER THE NEXT FEW WEEKS

In La Mesa, Calif., FBI agents searched Fuller's orderly apartment. They found a framed montage of photos of Kacie near his computer.

Dave had two computers: one in his apartment and the laptop he had taken to Arkansas. Authorities examined both, looking for other victims.

Soon, the FBI arrived at Sam's house with printouts: a picture of Sam, pointing to a photo of singer Justin Timberlake; a webcam picture of another of Kacie's friends; and Dave's Yahoo buddy list, which included the names of lots of Greenbrier kids.

Sam was alarmed. So was Jessica, who remembered clearly the night she and Kacie had sent Dave a picture of themselves posing with Kacie's dog, George.

Dave had wanted to see what Jessica looked like.

The FBI was quickly finding out that Dave Fagen, as Fuller was known online, had been a regular presence in teen chat rooms for at least two years. He also had been targeting three other girls about the same age as Kacie.

The first lived in Michigan. She met Fuller in the winter of 2000 in Yahoo's teen chat room. They had talked for several hours and the girl put Fuller, known then by the screen name daves_in, on her buddy list. He claimed to be a 17-year-old living in San Diego. The girl chatted with him every day. She told the FBI that Fuller was always a gentleman, sticking to innocent topics like school, friends and family.

Fuller had asked for her phone number, saying, "I want to hear your voice," but the girl said no. She also refused his offers to fly her to California. The girl corresponded with Fuller for nearly two years, primarily on a public-library computer. Fuller never learned her real name.

Another of Dave's interests lived in Dallas. This girl met Fuller online in March 2001.

She had never given Fuller her address, she told detectives, but in March 2002, flowers from a Dave Fagen had arrived at her home. The girl's father was furious. And that was the end of her correspondence with Dave.

In Pennsylvania, FBI agents discovered a third girl who knew Dave, but after making certain that she was safe, agents didn't press for details.

Investigators ran Fuller's DNA through a national databank, but that produced no matches linking him to other crimes. Authorities were surprised. Fuller's planning had been so meticulous, they thought he must have struck before.

A KILLER'S PLOT REVEALED

Fuller, police learned, made his first trip to Arkansas on Oct. 11, 2002, nearly two months before he executed his plan. He flew into Little Rock National Airport, Adams Field, where he rented a car, drove to Conway and checked into a Motel 6. No one is sure what Fuller did during this first trip to Arkansas, although police believe he spied on Kacie and the Woody home.

The weekend he was in town, Kacie was crowned seventhgrade queen at the annual Fall Festival's Night of Coronation. On Oct. 12, a Saturday night, Kacie wore her first grown-up dress, a long, shimmering black confection, and a self-conscious smile.

She had 52 days to live.

On Oct. 15, 2002, Fuller sent this e-mail to Alltel Communications : I am planning an extended trip to Arkansas and the ISP I am currently using doesn't have a local dial-up number there. Are you an actual ISP and if so, how do I get software and set up an account to use your service?

Two days later, Kacie turned 13. On Nov. 2, when he had his kids for visitation, Fuller bought a gun. He told them he needed it for target practice.

Kacie also had been shopping. She excitedly described her purchases in an e-mail to a school friend: I got a new sweat shirt today... its really cute... and it is YELLOW! Yellow is the best color in da world!

On Nov. 4, Fuller flew back to Little Rock, once again renting a car, driving to Conway and renting a room at the Motel 6. Two days later, he showed up at the Guardsmart Storage facility in Conway looking for the largest unit available. Fuller told one of the on-site managers that he traveled the country buying cars and needed a place to temporarily store vehicles.

On Nov. 8, he extended his stay at the motel. Authorities later speculated that Fuller had planned to abduct Kacie during this trip, but something thwarted him.

When he returned to California, Fuller went shopping again. He bought chain, duct tape and zip ties from his local Home Depot. He also obtained a bottle of chloroform from a chemical supply company. Soon he would pack his supplies in his Buick Regal for a final trip to Arkansas.

In Kacie, Fuller had found the perfect victim.

She was gullible, freely giving him her real name, address, phone number and pictures of herself. Also stored on Fuller's computer was a poem Kacie had sent him: It was about nine p.m.

When everything got so dim, In the road was a horse, How could things get any worse?

We hit it hard and fast, And in it came through the shattered glass, There was blood everywhere, The moon shone a big glare, I wondered if she was alright, This was one horrid night, We all were rushed in the room, Where my daddy lay full of gloom, I was only seven, I heard the prayer that said she was in heaven, Oh that was such a horrid night, And as I stared at the sky with fright, I wondered why she had to go away, Even though I knew now she'd be happy everyday, I hated horses from that day on, Because now my mommy was gone.

Such outpourings from Kacie were Fuller's inspiration. His fictitious aunt, who he said had been in a car wreck and was dying - like Kacie's mother - was key to gaining Kacie's trust and sympathy.

Byrd, the state police investigator, would later surmise: "On the night Kacie died, she was telling the Georgia kid the story [Dave] told her - how he was going to see his dying aunt and how [the aunt] was going to go meet Kacie's mother. As it played out, he was playing a mind game with her. He was talking about her.

"Kacie was the one who was going to meet her mother."

A YEAR LATER

When Fuller's parents learned of their son's crime and death from reporters, they were skeptical.

"My son Dave would not be involved in anything like that," Ned Fuller declared indignantly. "Don't bother me anymore."

But then the police came, and they had to believe. In the months that followed, Ned wanted to call Rick Woody, but the officers discouraged him.

"I just wanted to tell him how sorry I was and that I still - I can't understand - that Dave must have been out of his normal mind-set when this happened because he was never violent," he says now.

"I'm just sorry his was the daughter he got involved with. I'd have probably come charging out here with a shotgun if it had been me."

The Santa Ana winds will sweep across Southern California in the coming days, carrying the stinging smoke of wildfires. It is late October, a week before Halloween, and in the dusty, palm-dotted San Jacinto Valley, Sally Fuller has found serenity.

Sally is tall, lean and lightly tanned, her patrician features emphasized by the short, stylish cut of her salt-and-pepper hair. She lives in San Jacinto, just north of Hemet.

She now recognizes the red flags she missed: the late nights Dave wandered the neighborhood to talk on his cell phone; the tantrum when Sally proposed moving the computer out of his bedroom; his insistence that the couple have separate Internet passwords and e-mail accounts; the framed photos of a smiling young girl in Dave's new apartment.

At the time of Kacie's murder, Sally and Dave's divorce was not yet final.

Sally heard what her husband had done from the reporters who called as the SWAT team surrounded the storage unit. "I was not as surprised as I could have been because of how I saw him deteriorate," she says. "I guess I had this feeling - he is going to crash. He is just going to crash.

"My feeling is that this was the only time," she says, referring to Kacie's murder. "Of course, he was gone for months at a time, so I really don't know."

Sally has been cautious in what she has told her children. Dillon, now 12, knows that his father killed a girl and then himself. Stacie, 8, knows only about the suicide.

Dave's ashes are still in Sally's closet. Someday, when the kids are ready, she will take Dillon and Stacie to Mount Olympus to scatter their father's remains.

Rick Woody, now 46, sits in his dimly lit, paneled living room, staring at the row of photos that line his mantel.

There is his wife, Kristie, her striking features framed by a mass of dark, tumbling curls. And there is Kacie, who possessed the same soulful eyes and enigmatic, close-lipped smile.

"I've gone through all kinds of emotions," Rick says, his face unreadable. "I've gone through the bitter stage, the questioning-God stage, where I've asked, 'How can you take my wife and then turn around and take my little girl?'"

He recognizes the irony in this tragedy - that the man who became a cop to help others wasn't here when his own daughter needed him most.

Last spring, Rick agreed to allow federal and state authorities to share Kacie's story in a nationwide effort called "Innocent Images" to train law enforcement officers and educate parents - even though he isn't ready to hear the story in its entirety.

"I can't let this be meaningless," he says. "I've got to make it do somebody some good."

In June, the FBI presented Rick with one of 100 commemorative patches bearing Kacie's name. The blue-and-gold patch depicts a teddy bear sitting next to a computer. "Kacie Woody, 1989-2002" is printed on the computer screen. FBI agents and local law enforcement officers who are part of the Innocent Images task force will wear the patches.

Guilt and what-ifs haunt Rick. What if he had called in sick that night, like he had been tempted to do? What if he had kept a closer eye on Kacie's computer activities?

"It can't lead you anywhere but in a circle," he says. "You want to know everything that's going on in your kid's life and you think you've got a good idea...." His voice trails off. "You want to protect them...." Again, a pause before Rick concludes: "She didn't have any fears."

OCT. 28, 2003

White tombstones glitter against the late-afternoon shadows on this gray, overcast day. Crickets chirp, and a breeze rustles trees on the cusp of autumnal glory.

Rick pulls up on his motorcycle, parking directly in front of Kacie's grave. He takes off his helmet, walks to the grave and kneels. Eleven days have passed since what would have been Kacie's 14th birthday. Tenderly, Rick scoops up the cards and notes that Sam, Jessica and other friends have left.

In years past, Rick came here each Sept. 4, his wedding anniversary, to leave red roses for Kristie - one for each year they would have been married. This year, he left 22.

But now there is a second grave in need of flowers, yellow ones, Kacie's favorite. Rick comes here three times a week, usually on his motorcycle. Kacie loved to ride with Rick. So it seems fitting to thunder into this peaceful spot on his bike.

Kacie was excited when Rick bought a motorcycle. During their first excursion, she leaned this way and that, glorying in this new sense of freedom. Rick finally pulled over and lectured her about holding on to him. He needed to know she was still back there. But Kacie wasn't afraid of falling off. She was with her daddy.

Rick leans against his Kawasaki Vulcan and gazes at Kacie's gravestone. He is clad entirely in leather. On his jacket, just over his heart, is the FBI patch that bears Kacie's name.

Briefly, a burst of sunlight pierces the clouds, warming the shoulders, but not the stone, on which a white ceramic angel slumbers. For much of her short life, Kacie wanted to be an angel, just like her mother. In second grade, for a school assignment, she listed two goals: to become a gold-medal gymnast, and then, someday, to go to heaven to see her mama.

Kacie now lies next to her mother. The epitaph on her gravestone is a single line, an allusion to the heart-rending fulfillment of a second-grader's goal: I Am an Angel.

The declaration comes from a poem Kacie wrote in sixth grade: I'm an Angel I'm an angel, Sent from above, To spread the world, With lots of Love... "It was like someone put that in her head," Rick says, still leaning against his bike, eyes focused on the past. "So I thought it just belonged there."

Rick glances once more at his daughter's grave.

And then he roars off, the seat behind him empty without the joyful girl who once rode there, the one who dreamed of angels.

About this series

This series of stories is based on interviews with investigators and Kacie Woody's family and friends, as well as police reports written at the time and a transcript recovered from the Woody family's computer. All direct quotes in the narration are based on the recollections of those interviewed. The parents of Scott, a 14-year-old Internet friend of Kacie's from Alpharetta, Ga., asked that his last name not be published. Arkansas Democrat-Gazette reporter Cathy Frye interviewed Sally Fuller in Hemet, Calif.

Learn more about Kacie Woody's abduction in our full, four-part series:

2003, ARKANSAS DEMOCRAT-GAZETTE , INC.