LITTLE ROCK — Fourth in a series

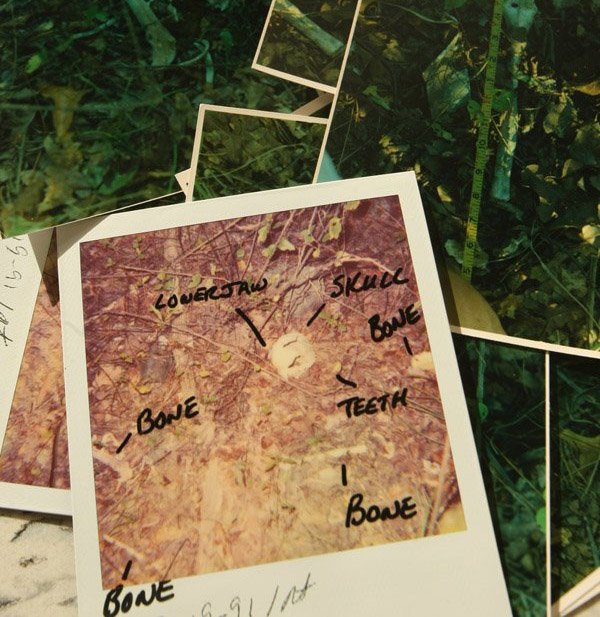

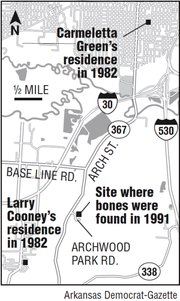

On Aug. 19, 1991, two cable workers surveying land off Archwood Park Road for future expansion stumbled upon the skeletal remains of what turned out to be a little girl.

The small, sun-bleached skull sat half-covered in leaves. A fist-sized chunk of bone was missing from the left side.

Someone had likely killed her with multiple blows on the head with a curved, smooth object. Ribs, pieces of her spine and pelvis were nearby.

Pulaski County sheriff’s investigators found only a few clues from the trash-strewn hillside in southern Pulaski County, including items that may not have been connected to the girl.

This is part 4 of a 6-part series. View all stories here as they become available.

The girl’s teeth, including several baby teeth, would be the detectives’ best chance at identifying the remains. There were 28 in all - six with fillings.

Not only could those fillings help identify the girl, but they were proof that someone had cared enough to take her to the dentist.

And that someone probably missed her.

About a month later, the Arkansas Democrat ran a short article on Page 9A that detailed for the first time publicly that the bones belonged to a black girl age 9-12.

Shannon Vita, area director for the Doe Network, read about the bones in the newspaper.

As a volunteer for Doe, a national group that works to identify human remains, Vita immediately began mentally ticking through a list of missing girls that might fit that description.

Lynn Smith disappeared from Hot Springs on Dec. 4, 1985, at age 16.

Jeanine Barnwell disappeared from Philadelphia a few weeks before Lynn. She was only 3.

Shaunda Green had been missing even longer. The 13-year-old was last seen in Michigan in October 1983.

But Vita had never heard the name Carmeletta Green, who disappeared from her Little Rock home Sept. 11, 1982, about 4 1 /2 miles from where the bones were discovered.

Carmeletta wasn’t on lists of missing people kept by the Doe Network, the Arkansas Crime Information Center or the National Center for Missing & Exploited Children.

Vita now wonders: If Carmeletta wasn’t on those lists, how many other missing girls does she not know about?

Another Doe Network volunteer called Little Rock law enforcement agencies, churches and schools, asking if anyone knew of any missing black girls.

No one she talked to - including detectives at the Little Rock Police Department and the Pulaski County sheriff’s office - mentioned Carmeletta.

“Nobody cared enough,” Vita said recently. “That’s how it is.”

How we got this story

As part of a six-month investigation, the Arkansas Democrat-Gazette interviewed 38 people and reviewed dozens of court and police documents to tell Carmeletta Green’s story.

Information about the skeletal remains and the work investigators did to identify them came from a file provided by the Pulaski County sheriff’s office and from the Arkansas Medical Examiner’s office and the National Missing and Unidentified Persons System (NamUs).

Information about the work by the Doe Network came fromvolunteers Shannon Vita and Betty Brown. Todd Matthews, regional coordinator for Nam-Us, also provided information.

Information about Lt. John Martin’s involvement came from interviews with him as well as the sheriff’s office file.

The Arkansas Democrat-Gazette went to the home of Carmeletta’s dentist, Dr. Roosevelt Brown, four times and left at least two telephone messages. Though Brown promised to look for the dental records, he has yet to do so. The newspaper had made arrangements with NamUs to compare the records Brown says he has with the teeth found on Archwood Park Road.

Information about the inmate’s claims regarding Larry Cooney’s suspected involvement in Carmeletta’s disappearance came from the sheriff’s office file and detectives’ accounts.

The Little Rock Police Department provided the murder statistics for 1991 and 1993.

A lot of police departments “don’t want to mess with old cases like that, especially African-Americans,” she said.

MISSED CHANCES

But when Little Rock police Lt. John Martin read about the bones found off Archwood Park Road in 1991, he had a gut feeling they belonged to Carmeletta.

Martin, who had worked on Carmeletta’s disappearance in 1982, immediately called Pulaski County sheriff’s Sgt. Carl Beadle.

Not only had the bones been found a short drive south from Carmeletta’s house, but they were exactly 2 miles from where suspect Larry Cooney lived in 1982.

Martin had always believed that Larry and his uncle Kenneth Cooney were involved in her disappearance. Larry had borrowed Kenneth’s car the night Carmeletta disappeared, and police had found what looked like blood in the back of it.

Larry’s conviction for molesting three children a few years before the bones were discovered only added to Martin’s suspicions.

While Larry was in prison, a fellow inmate told Little Rock police that Larry bragged about abducting, raping and killing Carmeletta with Kenneth’s help.

The inmate claimed that Larry said he buried Carmeletta in a cemetery. A police search of overgrown cemeteries in Pulaski County proved fruitless.

The investigation into the 12-year-old girl’s disappearance took a back seat to other cases until the bones were found in 1991.

Martin offered to make Beadle a copy of the “rather large” investigative file that he and other detectives had built over the previous nine years. Beadle took only a copy of the original incident report.

The two men never spoke about the case again.

Unless someone could prove that the remains were Carmeletta, Martin felt thatthe case belonged to the sheriff’s office.

Besides, he had other cases to tackle. In 1991, Little Rock police officers investigated 46 murders. That number escalated to a record 70 by 1993 when Little Rock was receiving national attention for gang-related crime in the city.

“We pretty much got caught up in our own doings,” Martin remembers. “And I just figured [the sheriff’s investigators] were doing whatever they needed to do.”

ABOUT MISSING CHILDREN

The U.S. Department of Justice estimates that 800,000 children a year are abducted or disappear. Most are taken by relatives and are found alive, the agency says.

On average, 115 children a year are taken by strangers who hold them overnight, demand ransom or kill them.

The Justice Department notes that the murder of an abducted child is rare, with about 100 cases in the United States each year. Seventy-six percent of those children are killed within three hours after they disappear.

Federal law defines a juvenile as anyone younger than 21.

Carmeletta Green is among more than 2,000 children reported missing nationally since 1982 who are still unaccounted for, according to a National Center for Missing & Exploited Children’s database.

The Arkansas Crime Information Center lists five missing and “endangered” juveniles in the state.

In Arkansas only one other child has been missing longer than Carmeletta.

Tony Allen, 16, was reported missing from Fort Smith in October 1978.

Recently published articles about Allen and other Arkansas missing-person cases can be found at www.arkansasonline.com/news/previousfeatures/missing/.

Mitochondrial DNA testing, a specialized analysis used to extract identifying information from bones, was not available in Arkansas in 1991 and was not used widely until after 2000.

So the quickest way to link the Archwood Park Road remains to Carmeletta would have been to compare her dental records with the skeleton’s teeth.

Beadle went to the office of Carmeletta’s dentist, Dr. Roosevelt Brown, asked for the records and left his card with a receptionist. When he didn’t hear from Brown after almost a month, Beadle called twice more. The dentist never returned his calls or provided any records.

After that, it appears that no one from the sheriff ’s office made any further attempts - by phone, visits or subpoena - to get the dental records.

Meanwhile, Katherine Murray with the University of Arkansas anthropology department examined the bones for the state medical examiner.

On Sept. 11, 1991 - exactly nine years after Carmeletta was reported missing - Murray mailed her report, along with a thick cardboard box packed with the tiny skeleton found on Archwood Park Road to then-Chief Medical Examiner Fahmy Malak in west Little Rock.

Someone on his staff tucked the box away in the basement morgue’s crowded “bone room,” which was nothing more than a storage closet.

The box would remain sealed in that closet for more than a decade.

Tomorrow: The box is opened, and DNA tests are finally done.

Front Section, Pages 1 on 12/09/2009