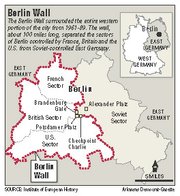

LITTLE ROCK — When the Berlin Wall was torn down and a new beginning was about to unfold across Europe, Russia was completely unprepared for thechanges that appeared to many in the West to be the natural result of the love of freedom and a widespread desire to throw off the repressive, criminal, monstrous legacy of Soviet communism. In 1989, Russia looked briefly into the mirror of its past, but the image reflected back was distorted and menacing. Two years later, the Soviet narrative came to an end, yet much in Russia today shows that the narrator may have prematurely announced his demise.

The impetus behind the desire to tear down the Soviet system in Russia had many sources. A desire to establish a free market, liberal democracy was only one of them-that is to say, a free market in the context of the legal structures without which liberal democracy is impossible. This stream of Russian/Soviet thinking was best characterized during the Gorbachev and Yeltsin regimes by figures like Alexander N. Yakovlev,Yegor Gaidar, and most recently Grigory Yavlinsky, the founder of the Yabloko Party. But another stream was characterized by Alexander Solzhenitsyn and many other writers and thinkers who viciously attacked the Stalinist system, yet did so from a very conservative position defined by Russian nationalism and Orthodox Christianity. Others more extreme than Solzhenitsyn challenged Soviet rule based on a nationalism considerably more xenophobic and anti-Semitic, and less humane.

The samizdat (literally, self-publishing) dissident phenomenon of the mid-1950s and onward is frequently seen as a concerted and coherent effort by like-minded individuals. Yet the samizdat movement united several contradictory strains of thinking against a common enemy. Samizdat or crypto-samizdat first appeared in the USSR not after Khrushchev’s thaw, but during the darkest days of the 1930s when Russian fascists published Nazi-inspired broadsides against Stalin. The walls that imprisoned the Soviet people in the Communist system also kept these powerful forces in Soviet society in check. When the Berlin Wallfell, so did these internal walls.

The most ominous development that quickly became apparent in the extremist press after Yeltsin took power was the so-called “Red-Brown Alliance”: the improbable alliance between the fascists and the Communists. To this only apparently contradictory phenomenon was soon added the Orthodox Church. What they all had in common was almost fanatical Russian nationalism, a rejection of the West, anti-Semitism, and a belief in the necessity of a powerful, autocratic central government. In the late 1980s and early 1990s newspapers and publications of all sorts represented this alliance by featuring the Orthodox cross and the Nazi swastika on their mastheads.

The Protocols of the Elders of Zion was published in mass market editions with a prefatory note by Henry Ford; the works of the white supremacist David Duke were on sale in the State Duma (the lower house of the Russian federal assembly); and the image of Joseph Stalin was relentlessly rehabilitated among the masses. In the mid-1980s, Stalin was little considered in public debate and would not have been identified by the majority of Russians as a great leader-today, he is viewed by the majority of Russians as one of the top two leaders in the history of Russia (along with Ivan the Terrible) and is ranked by Russians as one of the truly great world leaders (along with Mahatma Gandhi).

Yeltsin, his advisors and popular supporters were not capable of withstanding the force of these deep-seated currents in Russian social and political reality. In the eyes of the Russian nationalists, the economic chaos of the 1990s only confirmed that a liberal democratic state was a useless luxury promoted in Russia by Western “experts” for the benefit of the West. Democracy became, in the parlance of the late 1990s, dermocracy-literally, a “shitocracy.” Furthermore, the chaos of those years caused ordinary people to long for the remembered social and physical security offered by the Soviet system of welfare, however illusory or inadequate it may actually have been.

It is easy for us in the materially prosperous West to chide the Russians for their merely material concerns, but the recent panic in the United States over the collapse of the stock market does not even begin to replicate the anxieties that gripped Russia when its stock market lost, not 45 to 50 percent of its value as in the 2008-2009 U.S. stock market crash, but 75 percent of its value between January and August 1998. The background of Russian history is not the Great Depression of the 1930s but the Famine of 1932-33 (in which some 5 million Ukrainian peasants starved to death amid cannibalism and the complete eradication of their culture, and some 4.5 million peasants in Kazakhstan also perished); the Terror of the 1930s; and the total collapse of civil society.

Russia’s history in the 20th Century was traumatic under any definition. Revolution, destitution, terror, mass murder and savage repression were followed by the barbaric cruelties of World War II that claimed 20 million Soviet lives, new repressions, new forms of state violence, the threat of nuclear annihilation, and the brutally stagnant years of the Brezhnev regime. Gorbachev followed with the promise of liberalization, the relaxation of censorship, and the possibilities of “socialism with a human face.” Yet, theunderlying reality that informed Russian experience since the beginning of the last century was incompletely incorporated in the transformative process that led to Gorbachev’s rise and ill-founded hopes for fundamental change in Soviet society.

The West was deceived by the presence of samizdat in the 1960s, 1970s, and 1980s into thinking that Russian culture-not just dissident culture-was pervaded by a unified spirit of defiance against this system and could thereby change basic modes of thinking and sensibility. Culture, however, changes much more slowly than politics, and such change would be neither quick nor painless. Today, the return of Stalin into the classrooms and into the living rooms of ordinary Russians demonstrates that the turn away from 1989 is nearing completion in Russia-the image coming out of the mirror may look much different from what stands before it.

The question of why the image of Stalin, rather than a symbol of the Soviet system minus Stalin, has returned to daily Russian life can be answered only by recognizing that the Soviet system has no other visible symbols of success. Lenin’s short reign did not represent Soviet success and power so much as the triumph of Marxist thought. It was Stalin who fought the great battles against Trotsky, the Nazis and the sneering West. In the eyes of many today, Stalin vindicated the Soviet system, by transforming it into a great world power. No more “obsequiousness and groveling” before the West, or, as Stalin wrote in a letter to Maxim Gorky, “no more beggarly Russia.” In the end, the revival of Stalin has less to do with the image of Stalin than with the self-image of the Russian people, their powerful need to look into the mirror and see not themselves but their deepest aspirations reflected back.

Not everyone today shares this vision of the “new” Russian political order. Grigory Yavlinsky, the former deputy prime minister under Yeltsin, and the founder of the Yabloko party, whose aim is to establish a liberal democracy based on the rule of law, is quite pessimistic about the present political reality in Russia, which hesees as a form of “post-modern Stalinism”; that is, Stalinism without any of its outward signs. Others including Arseny Roginsky, the founder of Memorial, an organization established to commemorate the victims of the gulag and Soviet repression, keep alive the energy of samizdat from decades past. Journalists, such as Anna Politkovskaya, have refused to be silenced. Such groups and individuals could not have existed in the 1930s and could not have acted openly in the 1960s.

But Politkovskaya was murdered; Roginsky’s Memorial was broken into by government investigators on the eve of the 2008 Moscow Stalin Conference; and Yabloko has a following of only about 60,000 members. As Yavlinsky said to me in a recent interview, “as long as I stay on the reservation I can say whatever I like. The second I get off the reservation, I am a dead man.” He knows well the perimeter of that reservation. Twenty years after 1989, the deepest questions of theperestroika of Russian society, going back to 1956, remain. They will not be answered by political or economic success or failure but by the slow work of cultural transformation.

Jonathan Brent is executive director of the YIVO Institute. His most recent book is Inside the Stalin Archives. This article originally appeared in The New Criterion, Volume 28, November 2009, and is reprinted with permission.

Perspective, Pages 71 on 11/08/2009