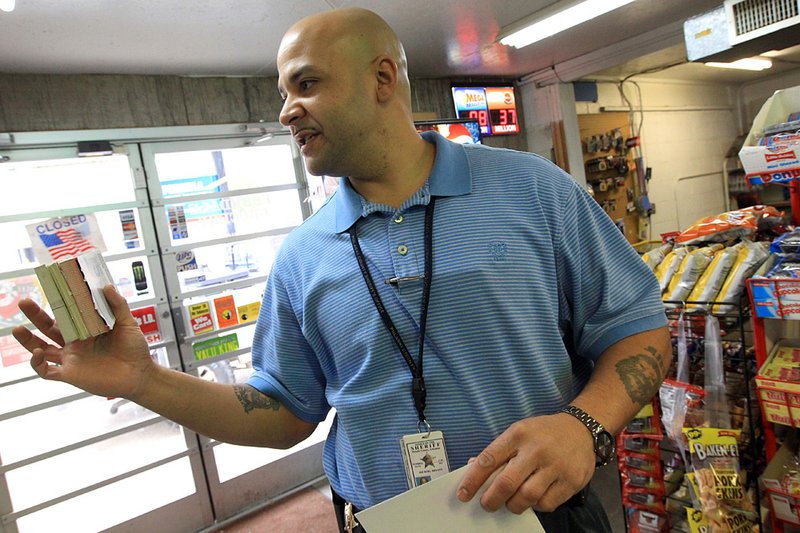

LITTLE ROCK — Pulaski County sheriff’s detective Michael Bryant is used to getting the looks of disbelief, uneasiness or outright skepticism. But they don’t affect him anymore because there’s not much he can do. The ink’s already dried.

“I got my first tattoo when I was 16,” Bryant said. “I got my initials put on my arm ... thought it was cool.”

Standing 6-foot-4, Bryant can be an imposing figure. A former football player, he has a big build, a badge and, of course, a gun.

Bryant, 31, also has eight tattoos. Three of them are in plain sight when he wears a short-sleeved shirt. One of them is a lion, another is an image of Jesus Christ, and the third says “Psalms 27.” Despite the religious nature of his markings, he said, the sight of a law enforcement official with visible tattoos puts people off.

“People look at you differently just because you have ink,” Bryant said. “ Especially older folks ... there’s been numerous occasions where I walk out of a car and up to a call and the first thing I get is that look.”

That look, for some law enforcement agencies, is reason enough to keep peacemakers like Bryant either wrapped up or off the beat all together.

Law enforcement agencies in the Little Rock area are taking different approaches to this relatively new development in police culture, which is forcing department heads to reconcile it with the old professional standards.

While it is acceptable for Bryant and other deputies with the Pulaski County sheriff’s office to sport a tattoo on their forearms, it’s unimaginable in North Little Rock.

University of Arkansas Little Rock criminology professor James Golden said tattoos weren’t an issue when he was an officer in Jonesboro - but that was 20 years ago. Golden said he suspects that the varying approaches and philosophies taken to handle a younger generation of police officers who might be more inclined to get “tatted up” are byproducts of the personalities at the top.

“For some chiefs, they’re going to take the side that it does not project a positive image,” Golden said. “For others it may not be a problem ... you might find some difference in opinion on what constitutes a professional image.”

That image has prompted action nationwide.

In 2003, the Los Angeles Police Department ordered its 9,000 members to cover up any tattoos while they were on duty. The San Diego Police Department and Los Angeles County sheriff’s office followed suit in the next two years. Houston, Dallas and St. Louis are other police departments who have adopted polices to prohibit officers from having body art that is visible while in uniform.

“We’re seeing a recent trend that allows tattoos with some restrictions like [covering],” said Gene Voegtlin, a spokesman for the International Association of Chiefs of Police. “No two departments are the same. ... It’s really a local decision on how different [police] chiefs want to handle the trend.”

Voegtlin said his organization has formulated policy models on issues ranging from administrative to operational procedures and standards,but it has yet to devise one for its 20,000 members when it comes to tattoos. The issue is still fairly new, he said.

“Tattoos are not necessarily a new development, but their presence and visibility in society has increased,” Voegtlin said. “The issue has become more prevalent because of the demographics involved. ... They’re fairly common in younger generations, in our recruits’ age groups. ... It’s more important now that [visible tattoos on officers] be addressed.”

A generational study from 2007 by the Pew Research Center for the People and the Press found that those in younger demographics are more tattooed than any before. The study found that more than a third of people ages 18-25 had tattoos.

Officer Carmen Helton, the head of recruiting for the North Little Rock Police Department, said that trend isn’t going anywhere.

“The generation today, they want to have tattoos. For us, I see it a lot in people just turning 21, and these are the ones I have to turn away,” Helton said.

In 2006, North Little Rock Chief of Police Danny Bradley wanted his department to put together a formal tattoo policy after hearing about an Oklahoma City police chief’s strange encounter with a job applicant. Bradley said the Oklahoma department had to put together a tattoo and body-modification policy after getting a qualified applicant who had horn implants, small pieces of silicone inserted under the skin to give the appearance of having horns.

For Bradley, tattoos - and horns, for that matter - are not acceptable.

“The world changes, and we have to change, too,” Bradley said. “But as far as visible tattoos on a police officer ... I don’t think our community is ready for that.”

In the policy, visible tattoos or intentional scars are prohibited for officers on duty. If an officer has a tattoo that would be visible when he’s in uniform, he may cover it up with a flesh-toned patch or Band-Aid, but the bandage can be bigger than 4 inches by 6 inches.

And an officer can have only one. If an applicant has more than one visible tattoo, he will have to apply elsewhere.

“We’ll lose, on average, about one or two applicants a year of good quality,” Bradley said. “But it’s a sound policy.”

He said the sight of tattoos on officers is contrary to the image he wants his department to project. Bradley regards tattoos, piercings and other forms of body modification as unprofessional. And he’s interested in maintaining the standards of his profession.

“The No. 1 thing for us is integrity. ... You have to earn it by how you present yourself,” Bradley said. “An officer doesn’t demand respect if he’s sleeved up and tatted out, that image doesn’t foster the respect and trust we want.”

Helton said it’s not only younger tattooed applicants who are barred from working in her department. It’s veterans, too. Police departments often hire applicants coming straight from the military, where there is a strong tattooing culture.

Helton said she has seen a variety of tattoos on former military members, ranging from religious symbols to unit-insignias to the names of children and loved ones. And even though they may not be offensive in their content, they’re against her department’s policy.

“I’ve gotten a few e-mails from people saying ‘if it’s good enough for the armed services’ why isn’t it good enough for us,” Helton said. “I tell them they can still be police officers, just not here.”

Arkansas State Police spokesman Bill Sadler said his department does not permit troopers to have visible tattoos while in uniform.

But Little Rock police officers can have them visible, as long as they don’t offend.

Little Rock police spokesman Lt. Terry Hastings says there is a stigma that comes with tattoos. He said tattoos are often associated with gangs, criminals and other “bad guys” in television and movies.

“[Tattoos] have never been a big issue here up until recently,” Hastings said. “In the last five years, you’ll see more and more officers with tattoos on them, some might be ex-military ... some might just be a statement or self-expression.”

According to a more recent study by Pew Research, the stigma associated with tattooing is mostly generational, with the majority of people over age 50 looking down on it, while those under 50 mostly unconcerned by it.

Hastings said he doesn’t think that the stigma gets in the way of good police work.Still, he said, there have been a number of conversations about tattoos among commanders and Little Rock Chief of Police Stuart Thomas, and his department has researched setting a tattoo policy, but no one has made any formal recommendations.

“Personally, I only have a problem if the tattoo is extremely offensive,” Hastings said. “It’s an issue not worth losing a good officer over.”

That’s exactly what happened in West Virginia, where a Wood County sheriff’s deputy was fired over a visible tattoo in April. The case has gone through two courts, and officials following it expect the case to reach the West Virginia Supreme Court before the matter is resolved.

Bryant sees some advantages to showing his tattoos while on duty. He said his “young and dumb” impulse to get inked on his forearms may give him an edge in dealing with some situation.

“If I go out and am working out on the streets, younger kids will see the tattoos,” Bryant said. “They think it’s cool. They’ll think I’m a cool officer, that I’m a cool guy.”

Helton said tattooed officers in North Little Rock are looking into alternatives in dealing with their department’s policy, including use of “Tat-Jackets,” skin-colored nylon sleeves that officers could use to keep their ink covered.

“There’s been talk of changing, maybe even allowing long sleeves all year round for some officers,” Helton said. “We’re trying to come up with options to accommodate people who do have tattoos, but for now, we go by the policies the chief has approved.”

Golden thinks police departments won’t consider tattoos professional until the rest of society has.

“I’m not sure there would be a large segment of society in central Arkansas that would look on an individual who has used their body as a canvas and say ‘that’s a professional image for officers,’” Golden said. “Police work will not be the leader in reducing the standard of professionalism by including officers with tattoos.”

Bradley couldn’t agree more.

“The public view of tattoos would have to change,” Bradley said. “If our culture and city accepted it ... if other professionals like doctors, lawyers, teachers had them, sure.”

Bradley said there are constraints on what officers can show, given the role they play in the community.

“We have to be sensitive to the community’s mores and norms,” Bradley said. “Because in the end, we’re the ones out there coming to your door at 3 a.m.”

Front Section, Pages 1 on 12/25/2010