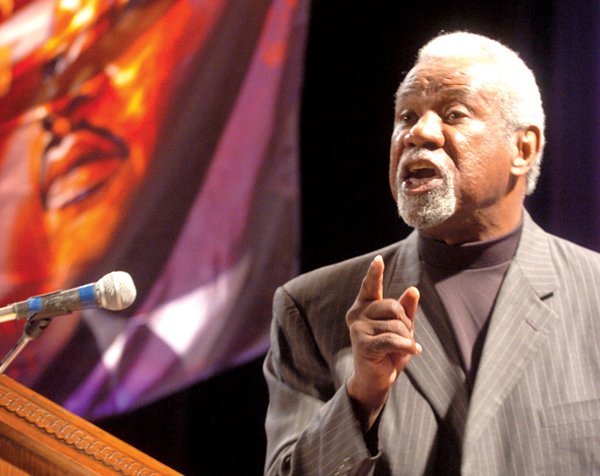

LITTLE ROCK — Nolan Richardson spoke last at the annual Arkansas Induction Ceremony of The Multi-Ethnic Sports Hall of Fame in Little Rock.

He didn’t wrap it up quietly.

Sure, Richardson dispensed the necessary niceties. He thanked the committee who’d voted him into his ninth hall of fame (“That’s a very deep blessing”) and such, but more than 70 people didn’t gather for the ceremony a few weeks ago at the downtown Comfort Inn to see the greatest basketball coach in University of Arkansas history bake cinnamon scones and steep tea.

No, they wanted to see a spark of the fire that had burned through the Southwest Conference and SEC in the 1980s and 1990s, leading to three Final Four appearances and a national championship.

They got it as Richardson alluded to himself and John Walker, his lawyer in a lawsuit against certain UA higher-ups based on allegations of racism in the workplace, as “troublemakers,” then came in for the landing by referencing one of his most-hated sports cliches: “‘It doesn’t matter if you win. It’s how you play the game.’ Now doesn’t that sound pretty? That’s bullsh*t. Oh it matters. Don’t let nobody kid you.”

Ah, that’s more like it.

That’s the old coach, who didn’t ride off peacefully into the sunset after he was relieved of his Razorback coaching duties in 2002. He’s since tried his hand at coaching the Panamanian and Mexican national teams, and is now the head coach of the WNBA’s Tulsa Shock.

Richardson’s words, however, didn’t ring totally true vis-a-vis the athletic careers of two of his fellow inductees and honorees.

What happens, after all, when you’re not allowed to win or lose, because the games themselves are closed to you? Then all that matters is how you play, or practice.

That was the predicament faced by Darrell Brown, a Horatio native who was the first black man on the University of Arkansas’ football team. Brown walked on to the team in 1965 and in practice was assigned the role of kickoff and punt returner. Essentially relegated to the status of pinata in cleats, he sometimes had to run without the benefit of blockers, fending off would-be tacklers with his superior athleticism while enduring racial taunts with a resolute will. Although Brown played in several freshman games, he never made the varsity and decided to quit after an injury in 1966. A few years later he was a UA law student involved in civil rights issues when he was shot in the knee while jogging on campus, said Brown, who became a successful trial lawyer.

His story was relayed a couple years ago by former Arkansas Court of Appeals Judge Wendell Griffin to Rus Bradburd, author of Forty Minutes of Hell: The Extraordinary Life of Nolan Richardson, at a time when Bradburd was struggling to continue the book. “So I thought if Darrell Brown and [honoree] Bob Walters and Nolan Richardson can do what they did, sure I can just keep typing for another year,” Bradburd recalled.

Brown’s story is obviously regrettable, but sometimes great athletes voluntarily choose to pursue playing games where competition takes a backseat to style.

That would be the case for Hubert “Geese” Ausbie, likely the greatest basketball player in the history of Little Rock’s Philander Smith College. During his senior year in 1959-60 only Elgin Baylor and Oscar Robertson scored more points. Ausbie, a multi-sport star, could have pursued opportunities in the NBA and MLB, but instead tried out for the Harlem Globetrotters. Ausbie made it, kicking off a 24-year career in which he would became known to the 115 nations to which he traveled as the “Clown Prince of Basketball.”

As he walked up to the podium for his induction speech, it became evident the clowning hadn’t stopped. Immediately after taking his new 20-pound crystal trophy, he asked Arif Khatib, the event organizer: “Can I sell it?” Then, he whipped out a bundle of papers — ostensibly his speech — and started joshing Richardson on how his bio in the ceremony’s guide was longer than anybody else’s. “Nolan, I’m gonna make up for it tonight,” said Geese, who lives in Little Rock. Ausbie released the bottom of his stack, and it cascaded into a column of eight papers stapled end-to-end extending to the ground.

The laughter died down a bit before he added: “Nolan, I even got it in Spanish.”