LITTLE ROCK — Arkansas’ urban areas are some of the most dangerous in the country if you believe everything you read.

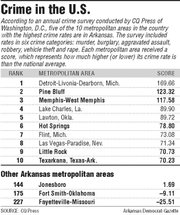

In its annual publication “City Crime Rankings,” CQ Press of Washington, D.C., has five Arkansas metropolitan areas on its list of the 10 most crime-ridden in the nation.

The Pine Bluff metropolitan area, which includes Cleveland, Lincoln and Jefferson counties, dropped from No. 1 in last year’s rankings to No. 2. The Memphis-West Memphis area follows at third, and the Hot Springs, Little Rock and Texarkana metropolitan areas are ranked sixth, ninth and 10th, respectively.

Yet area civic leaders, a UALR criminologist and the Little Rock Police Department are not convinced that the publication’s findings are particularly useful or accurate. And some think they domore harm than good.

“It’s detrimental to the development [of cities],” said Jeffery Walker, a professor at the University of Arkansas at Little Rock’s department of criminal justice.

“Little Rock has been working very, very hard to get new industry there ... and if I’m a business looking to expand and look at the CQ study, I’ll think all of my employees will get robbed or worse if we go to Little Rock.”

Pine Bluff Alderman Glen Brown says such studies perpetuate a negative perception of his community, one founded on statistics he says are “misleading” at best.

“It’s not like you walk down the streets [in Pine Bluff] and something bad’s going to happen to you,” Brown said. “Most of the crime in this study happens in very isolated, condensed areas. ... It’s not the whole community.”

Brown said Pine Bluff and the other cities featured negatively in the report have to work hard to break a vicious circle: High crime ratings keep away new industry, which keeps away new jobs, which leads to more crime.

“Those negative comments and those ratings, they play a big part in curbing industry,” Brown said. “Having those negatives ... a business looking to expand will look at you and say, ‘Let’s just move on to the next town.’”

P ine Bluff Alderman Wayne Easterly called rankings like the CQ Press’ unfair and says Pine Bluff ends up being tainted by all the crime that occurs in its surrounding counties.

“It’s always difficult to battle against that perception,” Easterly said. “[That perception] makes it difficult for recruiting [new business]; it makes Pine Bluff look worse than it is.”

The study drew its crime data from the FBI’s Uniform Crime Reporting Program, a national database that has documented the amount and types of crimes by localities for nearly 50 years. For this study, CQ Press researchers reviewed the incidents of murder, rape, robbery, aggravated assault, burglary and motor-vehicle theft from 400 cities and 347 metropolitan areas in 2009.

Then they measured the crime rates of the different locales against a national average based on incidents per 100,000 residents. They then evenly weighted the differences in percentages and folded the six crime categories together to reach a final crime “score,” which they say is a valid measure of an area’s crime rate when pegged to a national average.

The goal of the study, according to a statement from a CQ Press spokesman, is to provide the public as well as community leaders with “accessible, straightforward data which citizens can use and understand” when evaluating the prominence of crime in their communities.

That’s a goal that one critic thinks is one of the study’s lone good qualities.

“The goal of the study is admirable,” said Walker. “They’re looking to give the public something quick and easy that they can hang their hat on for decisions they may want to make.

“The problem is,” Walker added, “it’s not that simple. .... And in so doing, you pretty much destroy any quality findings that you could have gotten for something like this.”

Walker has been a criminologist at UALR for 20 years and has seen this same study come out every year since 1999. Its methodology remains unsatisfactory, he said.

“When I was involved in counterintelligence for the [Department of Defense], I had to give two-hour briefings every day, and finally my superior asked me if I could just give him a number so we could avoid the briefings,” Walker said. “I told him, ‘I could ... but it would severely misrepresent my findings.’ It’s the same thing going on here.”

The Little Rock Police Department reported 32 murders to the FBI in 2009, eight less than in 2008. Little Rock also saw its reported robberies take a modest tumble from 819 in 2008 to 799 in 2009. But it also saw a 24 percent jump in aggravated assaults and a 19 percent increase in motor-vehicle thefts, according to the FBI’s Uniform Crime Reporting Program.

This shift was enough to push Little Rock up in the study’s crime-rankings - it was 12th last year - because the CQ Press statistically weights the incidents of crime equally against a national average.

CQ Press spokesman Ben Krasney said the study only suggests one way to look at the numbers, which he emphasized are legitimate figures reported from official sources to the FBI.

“The numbers are the numbers,” Krasney said. “People may trash these rankings ... but police departments are providing them to the FBI. ... Some are just upset that they’re out there [for the public].”

Walker says the methodology used to develop a city’s crime “score” loses more than just nuance when it aggregates the data. He said that such simple distinctions don’t discern key differences between cities, such as history and demographics.

“The more precise you get the more skewed the numbers become,” Walker said. “What you’re doing is taking very disparate things and putting them together.”

For Walker, such statistics can only paint a detailed picture when confined to one city over time, while the current CQ Press study merely takes a snapshot.

The FBI cautions against using its data sets to make lists for these same reasons. The FBI joined the American Society of Criminology last year, according to Walker, in coming out against using raw data like the FBI’s Uniform Crime Reporting Program to generate lists of the “most dangerous” and “safest” cities to live in.

Little Rock Police Department spokesman Lt. Terry Hastings said he is very familiar with the problems involved in ranking cities by crime rate and believes his department in particular has gotten a bad rap.

“It’s bogus and skewed,” Hastings said. “These studies use numbers that are totally wrong for what they’re using them for.”

Hastings, along with Walker, say that the FBI’s figures should be taken with a grain of salt because not all law enforcement agencies report crimes the same way.

“Go to New York City and call the police for someone breaking into your car; they probably won’t report that,” Hastings said. “We report everything.”

Hastings also contends that the study is more interested in making money than depicting an accurate assessment of urban crime.

“They’re trying to sell you a book for $14.95,” Hastings said. “That’s all that is.”

Little Rock’s 32 murders in 2009 are roughly three times the national average, according to CQ Press. Authorities in the Pine Bluff metropolitan area had 14 more murders per 100,000 residents than the national average, the fourth highest rate for a metropolitan area in the U.S.

Walker says such statistics are important to know, but when looked at in only the short term, he says they do more harm than good in the long term.

He says many cities that perennially rank high in crime, like St. Louis, Camden, N.J., or New Orleans, become victims of a negative narrative.

Little Rock City Manager Bruce Moore isn’t rattled by the findings. He said the reports don’t present him and other city officials with any shocking revelations, only a reminder of problems they’ve been working on every day.

“I don’t put a lot of stock into those studies,” Moore said. “I meet with [Little Rock Police Chief Stuart Thomas] every week to go over where he’s putting resources and have been very pleased with the job the men and women of the department are doing.”

Violent crimes that have occurred in Little Rock from Jan. 1 to Sept. 10 this year have dropped 12 percent from the same period in 2009. Property crimes have fallen 10 percent over the same period, according to the Police Department.

“[CQ Press] does it to sell publications and all, but what I gauge is how people feel in our city about our crime problems,” Moore said. “It’s really a matter of perspective.”

Front Section, Pages 1 on 11/27/2010