NEW ORLEANS — When Hurricane Katrina struck five years ago, it displaced families and destroyed schools. It also unwittingly provided a chance to reinvent public education in a failing school district.

So was launched the nation’s biggest charter-school experiment. Today, 70 percent of New Orleans public-school students attend a charter school. No other city comes close. So educators, lawmakers and researchers are watching for results.

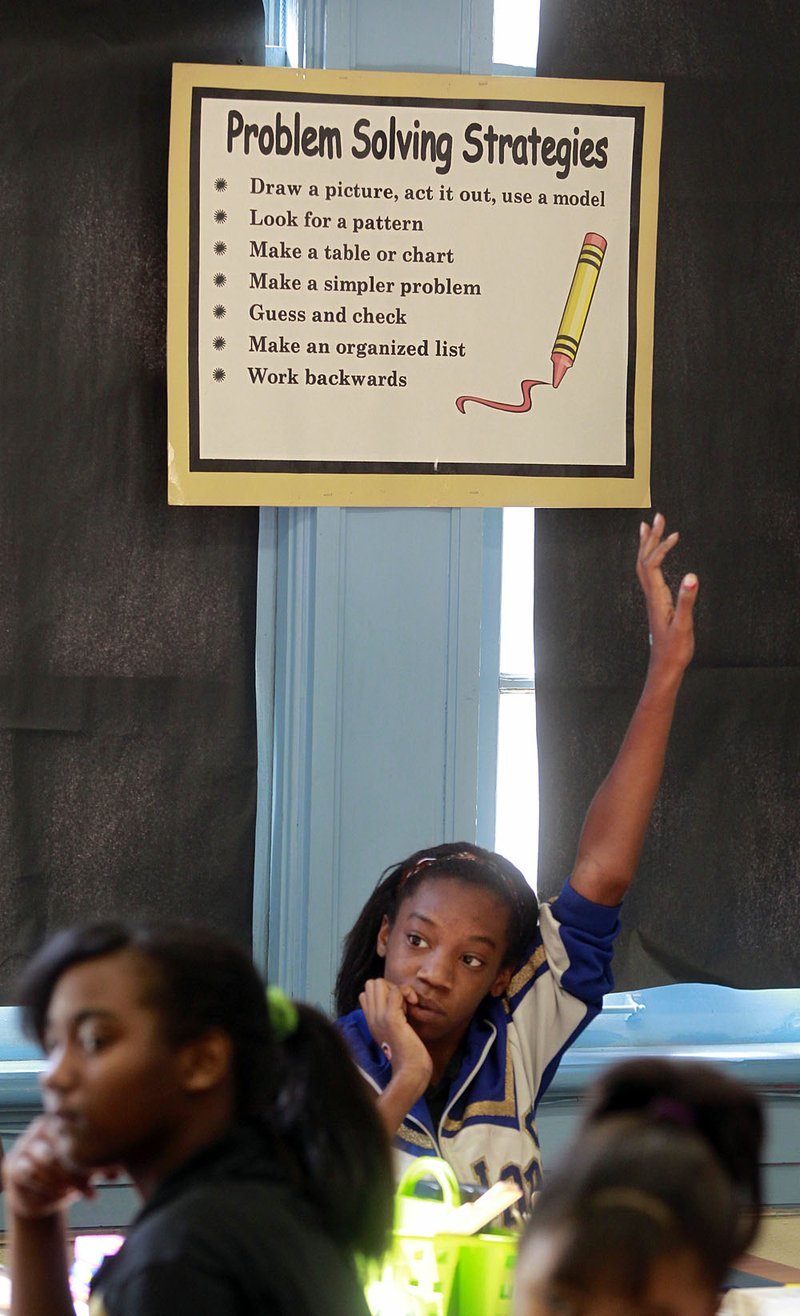

One early lesson: The relative freedom of charter schools - they’re independently run and exempt from many state education laws - appears to have been key to an overall boost in student performance in New Orleans.But the charter-school setup alone did not guarantee success. The best ones have strong leaders, capable teachers and a relentless focus on learning.

In other words, freedom in the right hands works.

The New Orleans school system once ranked among the country’s worst. And one of the worst schools was Sophie B. Wright Middle.

Wright chronically bore the state’s lowest rating, academically unacceptable. Just a handful of students passed state exams. Children got into fights and skipped class.

Today, Wright carries a two-star rating out of five, about the state average. Fights are down. Attendance is up.

What changed?

Five years ago, Wright became a charter school with its own governing board. Principal Sharon Clark said that autonomy has made all the difference.

“You are given the ability to really work with your community and your parents and make decisions that really benefit kids,” said Clark, a 43-year-old New Orleans native who started at Wright in 2001.

Under the old school system, superintendents came and went along with their pet reading or math programs. Teachers ran short on textbooks and basic supplies.

Wright was one of the few city schools to become a charter before Hurricane Katrina. And it was among the first, in January 2006, to reopen after.

Clark said she can make swift decisions like never before. She holds up a list of requests from her teachers. One wanted a digital projector, another needed workbooks. Yet another teacherasked for a smaller fifth-period class. Everything teachers asked for, they got within 30 days, Clark said.

As a charter, Wright was able to buy its own school buses, which saved money. And Clark could decide to put middle schoolers in single-sex classrooms (“Fewer distractions,” she explains) and do away with D letter grades to push students to work harder for a C rather than fail.

Wright also enjoys the freedom to not try new things. Of all the reading programs to cycle through under the old school system, Wright instructors preferred one called Success For All, so they kept it.

Some schools or districts favor a lock-step team approach, with teachers teaching the same thing the same way, to ensure consistency. Not at Wright.

“Teachers just know that they have to teach,” Clark said. “We give you anything and everything you need - the rest is up to you.”

Another charter school, New Orleans Charter Science and Math Academy - nicknamed Sci Academy - opened two years ago.

Benjamin Marcovitz, Sci Academy’s 31-year-old principal, said the charter structure makes it easier to customize to student needs. Two weeks into the first school year, instructors realized that most of its freshmen read only at a fifth-grade level. Over one frenzied weekend, the staff overhauled the English curriculum. Out went novels like Lord of the Flies. In came an extra class on writing andgrammar.

Before Hurricane Katrina, more than 60 percent of New Orleans public schools were rated unacceptable. After Katrina hit, the state placed theworst campuses into a state system, the Recovery School District. Many of those schools became charters.

The charter schools are doing better on average - state figures show that 13 percent of them were rated unacceptable this spring, compared with 65 percent of the Recovery district’s traditional schools.

That doesn’t mean charter schools are inherently better than traditional schools, experts say.

“The truth is there are good charter schools and there are bad charter schools, and there are good traditionally operated schools and ones that are failing,” said Shannon Jones Couhig, executive director of the Cowen Institute for Public Education Initiatives, a Tulane University think tank.

Despite the growing popularity of charter schools, most experts say simply converting urban school systems into a sea of autonomous charter schools is not the answer.

In New Orleans, the hastyswitch to so many independent charter schools created some unintended consequences.

“There’s no one paying attention to all schools in Orleans Parish,” Couhig said. “There is a need for some sort of entity to oversee this, to make sure kids’ needs are being met.”

Some charter schools have been accused of turning away children with disabilities or giving them an inferior education.

And having principals oversee academics, budgeting, hiring and building requires a lot of expertise.

Further, the schools are far from fixed. Extra federal dollars and donations that had doubled spending to $16,000 per student are now drying up.

And Louisiana must decide whether Recovery School District campusesshould return to the New Orleans city system.

At a recent public hearing, one Wright parent made his wish clear:

“The choice we have now is a better choice,” James Watson said. “All of the parents at Wright have access to the principal, to the administrators. Our voices count.”

Front Section, Pages 3 on 11/28/2010