LITTLE ROCK — At age 14, Anna Cone doesn’t know how to make some capital letters in cursive and prints all of her schoolwork.

Anna, an eighth-grader who makes good grades at Greenbrier Junior High School, said most of her friends also struggle with cursive writing.

“I write in print all the time,” she said. “I know some [friends] are working [on cursive writing] on their own, just so they’ll be prepared.”

While Anna said her teachers “really hit [cursive writing] hard from the third grade to the sixth grade,” these days it’s often taught less.

As technology becomes increasingly accessible to children and adults, some fear cursive writing and penmanship are going the way of Latin, slide rules and letters - the stamped, handwritten kind that Anna sometimes has trouble deciphering.

“If my grandma writes me a card or something, she always writes me in cursive, and sometimes it’s tough to read,” Anna said.

Rather than write back, Anna calls her grandmother.And she phones or text-messages her friends.

People are increasingly and rapidly sending everything from the shortest of thank-you notes to contracts, recipes and even book manuscripts by e-mail. They store the most personal of journals on their laptops. And when they’re not e-mailing, they’re often sending terse, abbreviated text messages or online chat messages.

It’s unclear whether schools are reacting to or contributing to the trend away from cursive penmanship, or perhaps both.

STATE STANDARDS

Under Arkansas’ public school standards, teachers begin introducing printing in kindergarten, when children are expected to learn to form letters correctly. The manuscript process continues through the second grade, when children should write “legibly in manuscript,” the standards say.

But unlike the days when young baby boomers began cursive writing in the second grade, most Arkansas public school students now don’t study it until the third grade. And there often is relatively little pressure to master it well.

By the fourth grade, the standards call for teachers to focus on writing format, audience and paragraphs rather than penmanship.

Further, not all schools grade penmanship anymore. A national survey of primary school teachers in 2003 found that only three of every five teachers reported grading students on penmanship.

Among Arkansas schools that do not grade it are two of the state’s largest, the Little Rock and Conway school districts.

Peggy Woosley, Conway’s director of instructional services, said the district encourages children to write legibly.

“We have a lot of kids that print,” she said. “If it’s legible and they do well with it, that’s fine.”

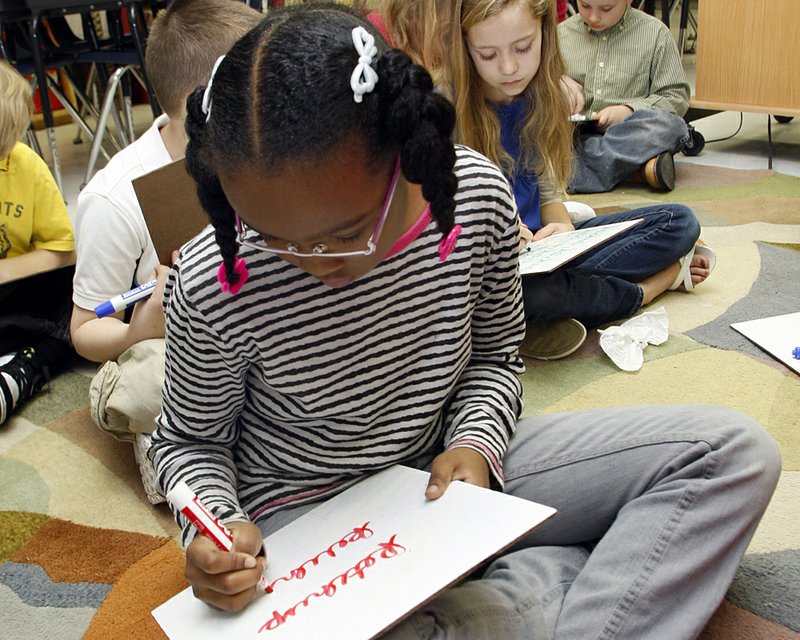

At Conway’s Theodore Jones Elementary School recently, third-grade teacher Amy Howell’s students recently huddled around her on the floor for their first work of the morning: cursive writing.

They focused on the letter “k” and began by watching Howell write the word “ketchup.”

Then they took red, blue and green markers and practiced writing “k” on erasable white boards. After “ketchup,” they slowly wrote “knife” and finally, at one little boy’s suggestion, “Kit Kat,” a popular candy bar.

“Watch how I go from one letter straight into the next letter,” Howell told the youngsters.

“Let’s see you do it,” Howell later told Nataly Rveda as she gently guided the child’s hand in writing “knife.”

Within a matter of months, though, the pressure for the children to write in cursive will be gone.

Statewide, teachers may allow students in fourth-grade and higher to use either printing or cursive, said Latanya Taylor, public school program adviser for the Arkansas Department of Education.

WHAT’S NOT ON THE TESTS

“With the presence of technology, there may be more discretion concerning using cursive writing because many students have access to computers,” Taylor said.

Penmanship is not covered on standardized tests, said Gayle Potter, the department’s director of curriculum and assessment.

Some believe that omission is an important reason why cursive writing doesn’t get more attention in schools nowadays.

Standards developed by the National Governors Association and the Council of Chief State School Officers cover writing, “but there’s not much about the sub skill of handwriting,” or even printing, said Vanderbilt University education professor Steve Graham, who has surveyed the teaching of handwriting.

“If handwriting’s not there, then it’s less likely to be taught,”Graham said. “We don’t test for that at the state levels. ... That reduces its cachet.”

Graham said the number of fourth- through sixth-grade teachers around the country who teach handwriting is “pretty small.”

“There’s kind of a tendency to teach to the test today,” agreed Tamara Plakins Thornton, author of the book Handwriting in America: A Cultural History. “So whatever is testable gets taught, and handwriting in general is not tested.”

Further, as technology’s role grows in schools, keyboarding will become an increasingly important subject, Graham said. But he noted that students still do most of their work in schools by hand rather than by computer.

“Paper and pencil are the most portable and cheapest modes we have now, so they rule in school.” Yet most writing at home and in the business world is done electronically, Graham said. “I don’t see us reaching that [point] at schools for a good while.”

WHAT’S TAUGHT

Graham was among six researchers who in 2003 surveyed how 169 first- through third-grade teachers taught handwriting.

The study found nine of 10 teachers indicated they taught handwriting an average of 70 minutes per week.

About 80 percent of firstand second-grade teachers taught manuscript, or printing, while about 80 percent of third-grade teachers taught cursive, Graham said.

More than half of the teachers indicated handwriting difficulty influenced the time students took to finish written assignments, adversely affected quantity and quality of writing, and resultedin lower grades on written assignments.

About two out of every five teachers indicated that poor handwriting had a negative impact on spelling, impeded note-taking and adversely influenced how children viewed themselves, the researchers reported.

Yet Thornton, a history professor at State University of New York, said she is not sure penmanship really has declined, though people have long complained it has.

“In the Golden Age [of the early 20th century] ... there was an enormous amount of time put into penmanship education,” Thornton said. “One thing to think about is, do we really want to spend that much time on it? Maybe you get results from it, but there’s also a cost. Maybe a certain amount of decline is good” so more time can be devoted to other needs.

But if there has been a decline, she said, it started in the late 1800s with the typewriter’s introduction.

“I think people are mainly comfortable with keyboarding at this point,” Thornton said. “I can’t see penmanship completely lost .... There’s a niche,maybe a smaller niche” now.

As for 14-year-old Anna, she fears she “will struggle” later with her inability to write cursive. She already must “sign a few things” and said she knows she will “have to sign other things like checks” as she gets older.

Indeed, Regions Bank spokesman Mel Campbell said the company’s policy for people who cannot sign their checks in cursive would be the same as for people whocannot write at all or who are disabled and use a mark for their name: Two bank employees would have to attest to the printed name being that person’s mark.

Jimmy Bryant, the University of Central Arkansas’ archivist, believes the trend away from cursive and traditional letter-writing will also hurt historical collections.

“It’s highly unlikely people are going to print every e-mail they write,” Bryant said. “So I see that there will be a time in the near future when archivists will receive collections that have very little correspondence, professionally or personally, because of e-mail.

“When those things disappear, that’s really going to hurt [what] we know about” a person, he said.

“Penmanship is dying,” Bryant said. “I asked my students last semester how many of them wrote in cursive when they wrote cards to people or letters. Not one of my 40 students said they did that.”

“I think it’s a sad thing that people no longer know how to write,” he said. “We have to have [electronic] machines now in order to communicate.”

Front Section, Pages 1 on 03/07/2011