LITTLE ROCK — In my time I have known couples quite like David and Jackie Siegel, the subjects of Lauren Greenfield’s remarkably compassionate documentary The Queen of Versailles. I thought of them, not unfondly, as my “rich friends,” though their wealth, while considerable, was an order of magnitude shy of what the Siegels amassed.

What my rich friends had in common with the Siegels was a curious quality of innocence yoked to an unshakable sense of entitlement and confidence in their own judgments, however spurious or ill-formed. They seemed to believe their money conferred upon them ultimate wisdom and taste - that they were incapable of committing gaffes or seeming rude or gauche. While they were too polite to say so, it was as though they genuinely believed their money made them better people. They seemed to believe Scott Fitzgerald’s facile theorem that the rich are “very different from you and me.” (Yes, Hemingway rejoined, they have more money.)

This wasn’t so hard to understand when you considered the deference with which most people treated them. One of the great unsayable truths about the American dream is that it is a bit of a Ponzi scheme - politicians in thrall to the rich are able to convince most people to vote against their economic self-interest because our system admits a glimmer of hope that anyone, no matter how lowborn, can rise to the top. And the surfeit of obviously untalented celebrity millionaires showcased on TV shows and court proceedings reinforces the idea that it really could happen to anyone.

Anyway, Greenfield succeeds to the degree that she exposes the notoriously trashy Siegels as fully human and sad, as people who are different from us mainly in that they are unused to being refused. They seem as children - petulant and spoiled children, perhaps, but of tender sensibilities. However much you’re prepared to hate them when you walk in the theater, you’ll probably leave feeling at least a little sorry for them.

Jackie is, on first blush, a trophy wife, some 30 years younger than her billionaire husband, the founder, owner, president and chief executive officer of Westgate Resorts, the world’s largest time-share vacation property business in the world. She was a model and a former beauty queen, but she also managed to work for a time as a computer engineer at IBM.

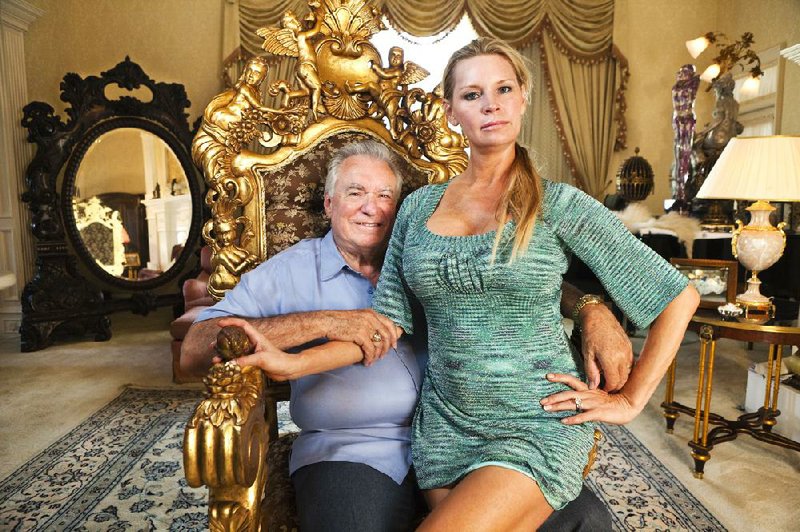

When the film opens in 2007, the Siegels are flying high. Sitting on what looks suspiciously like a gilded throne, David intimates that he single-handedly had George W. Bush elected president, through means that might not have been entirely legal. He and Jackie live - with their seven children, Jackie’s at-risk teenage niece, assorted fluffy white lapdogs and other miscellaneous pets - in a 26,000-square-foot mansion in one of Orlando’s gated communities. Their biggest problem is that they’ve outgrown the property - “we’re bursting out the seams,” Jackie says - and so they’ve begun construction on a 90,000-square-foot house that will be the largest private residence in America. They’ve modeled it (unironically) on the Palace of Versailles, and Jackie’s primary occupation seems to be buying Louis XIVesque furnishings to fill it up.

But then the recession hits, and Westgate proves particularly vulnerable, as its business model relies on the ability of working-class Americans to obtain cheap credit. Suddenly people are finding it hard to keep up the monthly notes on properties they use only one week a year. This slowing of Westgate’s cash flow, combined with what David seems to view as the intractability of his company creditors (he voices a variation on the theme that they “just won’t work with the businessman”), threatens another prize project, a highrise in Las Vegas.

The film alternates between scenes of the self-dramatizing Jackie indulging her propensity for conspicuous consumption and David grinding away to find a solution to his financial woes. A half-finished Versailles is abandoned and put up on the market; some 19 members of the family’s housekeeping staff (along with 7,000 Westgate employees) are laid off. Jackie weepily considers the possibility that her children might actually have to go to college. Dog excrement and dehydrated lizards threaten to turn the Siegel family home into a 21st century Grey Gardens.

Darkness permeates the final act, as David retreats into his cluttered study, ranting about the bills and his unruly family. He emerges as a shallow and pitiless man - a middle-aged son from a previous marriage admits his relationship with his father is strictly business - and we sense he’d rather give up his kith and kin than his Vegas high-rise.

There are moments in the film that strain credulity. David Siegel has complained that (among other things) the filmmakers staged certain scenes, such as Jackie’s riding a jet ski in a fur coat and going through a McDonald’s drive-through in a limousine. And I was bothered by a scene where Jackie, having decided to economize by flying commercial and renting a car (rather than hiring a limo), imperiously asks the clerk at the Hertz counter, “Where’s my driver?”

There is no way she doesn’t know better. She had a modest upbringing in New Jersey, she worked for years before being snapped up by David - she’s not stupid; she understands how car rental companies operate. She wants to give the impression she’s more naive (and hence less culpable?) - that she in fact is very different from you and me. Well, isn’t that special?

Well, no, not really.

The Queen of Versailles 87 Cast: Documentary, with Jackie Siegel, David Siegel Director: Lauren Greenfield Rating: PG, for thematic elements and language Running time: 100 minutes

MovieStyle, Pages 31 on 08/17/2012