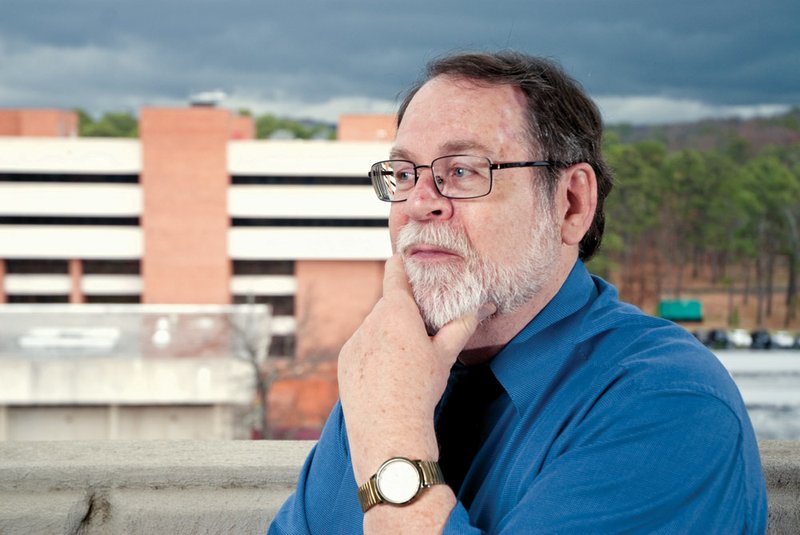

CONWAY — Conway’s Bruce Plopper, 67, became a teacher when he was about 12, but it wasn’t a straight route to the classroom.

When he was growing up in Liverpool, N.Y., he knew a little girl in the neighborhood who had a speech impediment. Pammy Sue couldn’t say her S’s.

“One day it was raining, and I taught her to say ‘S,’” Plopper said.

He practiced with her to say “Sally sells seashells at the seashore.”

“She was able to avoid having speech therapy. I said, ‘Yeah, teaching would be a possibility,’” Plopper said.

First, he had to try an eclectic laundry list of other jobs — then nearly flunk out of Michigan State University in electrical engineering — before he fell into what has been an award-winning career that has spanned 45 years.

He doesn’t teach speech. Never has.

Plopper will retire Dec. 31 as professor of journalism at the University of Arkansas at Little Rock, where he’s spent the past 22 1/2 years.

In hindsight, Plopper seemed perfect for a job in journalism, but it wasn’t his first choice.

One of Plopper’s first jobs as a child was tagging after his older sister going up and down their street to collect used newspapers and magazines, which they read before their mother stacked them in her 1937 Pontiac to sell.

His father worked for the Great Atlantic & Pacific Tea Co. Inc. (A&P grocery stores), and his mother was a legal secretary before she had children. Plopper learned to type on her 1930s typewriter, which he still has.

Plopper later shoveled sidewalks in his neighborhood and delivered newspapers up and down the street.

In the summers, he worked as a clerk at the A&P to help pay for classes at Michigan State.

“Dad always said, ‘Oh, a college

professor’s life; that’s a great life,’” Plopper said, but he started in electrical engineering because that’s what a kid from his neighborhood had done.

Plopper didn’t do well in that, so he had to switch gears.

When he went to register for his junior year, he was told he couldn’t until he declared a major.

“The only A I had was in psychology. I said, ‘I’m a psychologist!’”

On the list of quirky jobs Plopper has had, he was a baby-food salesman between college at Michigan State and going to graduate school at Southern Illinois University.

He received a master’s degree in social psychology from Southern Illinois, and at age 21, he gained his first classroom experience teaching two statistics labs, which he loved.

“It was fun — it was a lot more fun than selling baby food,” he said.

Psychology, not so much. Frankly, the subject bored him.

“I said, ‘There’s got to be something more exciting,’” he said. “I fell into journalism.”

He moved to Los Angeles and worked an hour away at a record store, first as a clerk and then as personnel director, before getting a job as a teller at a large savings and loan in LA. He and other employees thought the monthly employee magazine was boring.

Plopper, who had advanced to operations manager, and other employees started their own satirical newsletter. The personnel director called him in and told him to stop it. Three months later, the magazine editor resigned, and the personnel director offered Plopper the editor’s position.

“I went to a used book store in LA and bought four journalism books,” he said. Then he hired an assistant who was “a really great talent.”

Plopper also met his wife, Debbie, who worked for the same company, on a blind date in 1974, and they married in 1975.

After he earned a doctorate in journalism at Southern Illinois, the couple moved back to Los Angeles, where Plopper got a job editing publications for the building industry. During the interview, the president of the company looked over Plopper’s resumé, unimpressed, and said, “You’re long on education; short on experience. Why should I hire you?”

Plopper showed the president the company’s publications that Plopper had marked up with corrections while waiting.

The president asked Plopper how soon he could start.

From there, Plopper got a job with Gambling Times, where “I met a lot of strange people,” he said.

He edited a book by a million-dollar blackjack player, but he couldn’t get publicity until the guy got thrown out of a casino.

After that, Good Morning America and other media outlets called Plopper to get an interview with the man.

One thing that experience taught Plopper was, “I learned not to gamble,” he said.

His first teaching job was at Humboldt State University in California, filling in for someone on sabbatical.

Plopper went to Missouri Western State College in St. Joe, Mo., with the promise that he’d be the head of the journalism program, which had only a minor.

A new president nixed the idea of making journalism a major, so Plopper left and took a job in 1985 at the University of Central Arkansas in Conway.

“It seemed to be the nicest place. The shock wasn’t there; we’d lived in Southern Illinois,” he said.

The pay wasn’t good and caused a strain on the family.

“Debbie and I were sitting on our bed asking, ‘How are we going to get money for a baby sitter next week?’ and the phone rang,” he said.

It was Jay Friedlander, then-chairman of the UALR Department of Journalism, offering Plopper a job.

He started in the fall of 1990 and made his mark.

“For me, teaching really became a lifestyle,” he said. “I think everybody’s work should be a lifestyle.”

That means it’s not work, he said.

That’s his advice for would-be journalists: “Make sure you’re having fun.”

One of Plopper’s most intense areas of interest has been student press rights.

“My mentor at Southern Illinois, Dr. Robert Trager, had a passion for student press rights and wrote at least two books on it,” Plopper said.

“He instilled in me the value of rights for students, and that was it.”

Plopper was integral in passage of the Arkansas Student Publications Act in 1995, working with the Arkansas High School Press Association.

“Students and teachers do not shed their constitutional rights at the schoolhouse gate,” he said.

“I was relieved that the Arkansas Legislature finally did something,” although it wasn’t a “radical act,” he said.

Plopper was the thorn in the side of some Conway School District officials in the ’90s, too.

When they began to consider drug-testing students in extracurricular activities, he went to school board meetings and inundated board members with studies showing that drug testing didn’t work.

They passed the policy anyway.

Then, to put his money where his mouth was, he and two other families got together and sued the school district on behalf of their children.

Plopper worked with a school committee on a solution, and the drug-testing policy was eventually overturned.

His efforts in journalism have not gone unnoticed.

Just a partial list of his honors include being a four-time Laurence Campbell award winner from the Association for Education in Journalism and Mass Communication for excellence in research. Plopper was also the Arkansas Press Association Journalism Teacher of the Year in 2008 and was honored more than once by UALR for his teaching.

He insists, though, that better than any award is when former students tell him he made a difference in their lives.

“With Dr. Plopper, it wasn’t enough to simply have an answer to a question; glib didn’t cut it,” said Mary Hightower, assistant director of communications/marketing for the Cooperative Extension Service in Little Rock. “He required a well-reasoned answer. I liked that he pushed his students and that he was a stickler for good writing and grammar.”

Former student Erica Paladino-Sweeney of Little Rock emailed Plopper when she heard he was retiring and wrote, in part:

“You really were the best teacher I ever had. I don’t think I have ever worked as hard as I did in your classes, and I learned so much, even how to think differently. You always seemed to care about your students and pushed everyone to do their best.”

Including himself.

Senior writer Tammy Keith can be reached at (501) 327-0370 or tkeith@arkansasonline.com.