NEW YORK — American authorities on Tuesday cited “astonishing” dysfunction at HSBC after the British bank agreed to pay $1.9 billion in penalties for helping Mexican drug traffickers, Iran, Libya and others under U.S. suspicion or sanction to move money around the world.

While the penalty is the largest ever imposed on a bank, U.S. investigators stopped short of charging executives, citing the bank’s immediate and full cooperation as well as the damage that charges might cause on economies and people, including thousands who potentially would lose jobs if the bank collapsed.

The settlement avoided a legal battle that could have further savaged the bank’s reputation and undermined confidence in the banking system. HSBC does business in almost 80 countries, so many that it calls itself “the world’s local bank.”

However, outside experts said it was evidence that a doctrine of “too big to fail” or at least “too big to prosecute” was alive and well four years after the financial crisis.

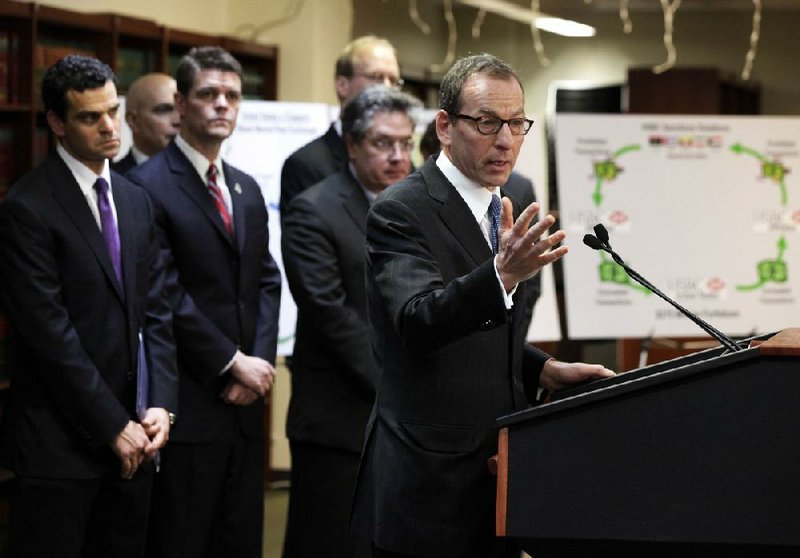

Lanny A. Breuer, assistant attorney general of the Justice Department’s criminal division, cited a “stunning, stunning failure” by the bank to monitor itself. He said that it enabled countries subject to U.S. sanction — Cuba, Iran, Libya, Burma and Sudan — to move about $660 million in prohibited transactions through U.S. financial institutions, including HSBC, from the mid-1990s through September 2006.

Officials noted that HSBC officers in the United States had warned counterparts at the parent company that efforts to hide where financial transactions originated would expose the bank to sanctions, but the protests were ignored.

HSBC even instructed an Iranian bank in one instance how to format messages so that its financial transactions would not be blocked, Breuer said at a news conference announcing the settlement.

“The record of dysfunction that prevailed at HSBC for many years is simply astonishing,” Breuer said.

U.S. Attorney Loretta Lynch in Brooklyn said the bank’s “blatant failure” to implement proper anti-moneylaundering controls permitted drug organizations in Mexico to launder at least $881 million in drug proceeds through HSBC Bank USA, violating the Bank Secrecy Act.

Court documents show that HSBC expanded its banking links with Mexico in 2002 when it acquired Mexico’s fifth-largest bank with approximately 1,400 branches and 6 million customers. According to the documents, HSBC’s head of compliance acknowledged at the time that what became HSBC Mexico had “no recognizable compliance or money laundering function ... at present.”

The government also alleges that HSBC intentionally allowed prohibited transactions with Iran, Libya, Sudan and Burma. The bank also facilitated transactions with Cuba in violation of the Trading With the Enemy Act, according to court documents.

“HSBC is being held accountable for stunning failures of oversight — and worse — that led the bank to permit narcotics traffickers and others to launder hundreds of millions of dollars through HSBC subsidiaries and to facilitate hundreds of millions more in transactions with sanctioned countries,” Breuer said in a statement.

Besides forfeiting $1.25 billion in its deal with the government, HSBC also agreed to pay $665 million in civil penalties, including $500 million to the Office of the Comptroller of the Currency and $165 million to the Federal Reserve.

“We accept responsibility for our past mistakes,” HSBC Chief Executive Stuart Gulliver said. “We have said we are profoundly sorry for them, and we do so again.”

HSBC conceded that its anti-money-laundering measures were inadequate and that it has taken big steps in beefing up its controls. Among other measures, it has hired a former treasury undersecretary for terrorism and financial intelligence as its chief legal officer.

The bank also said it has reached agreements over investigations by other U.S. government agencies and expects to sign an agreement with British regulators shortly.

Even with such internal changes by the bank, the decision not to prosecute was “beyond obscene,” said Bill Black, a former U.S. regulator for the Office of Thrift Supervision who now teaches at the University of Missouri-Kansas City.

“Regulators are telling us, ‘Yes, they’re felons, they’re massive felons, they did it for years, they lied to us, and they made a lot of money ... and they got caught red-handed and they’re gonna walk,’” he said.

Black disputed the government’s concern that indicting HSBC could take down the financial system.

“That’s the logic that we get stability by leaving felons in charge of our largest banks,” he said. “This is insane.”

Breuer defended the government’s agreement with HSBC. He said that U.S. employees in particular seemed duped by criminal enterprises taking advantage of HSBC oversight policies that over decades became increasingly lax.

Court documents showed that the bank let money 2006 and 2009 slip through relatively unmonitored, including more than $670 billion in wire transfers from HSBC Mexico, making it a favorite of drug cartels and money launderers. HSBC Bank USA at the time rated Mexico in its lowest risk category.

Top executives who felt “the pressure of the bottom line” continually cut that staff that might have discovered how criminal enterprises were taking advantage of the bank, Breuer said.

Officials noted that the deal for the first time resulted in U.S. court supervision of a foreign banking institution and lengthy monitoring of a radically changed bank that had changed all its top management.

The HSBC settlement is the latest scandal to hit banks since the financial crisis started in 2008.

On Monday, Standard Chartered PLC, another British bank, signed an agreement with New York regulators to settle a money-laundering investigation involving Iran by paying a $340 million penalty.

“These banks are operating in an environment where you can’t afford to have uncertainty attached to your name, and they are dependent on confidence from their investors,” said Sabine Bauer, director of financial institutions at Fitch Ratings. “And that makes them keen to get past such events very quickly and settle.”

Analysts said the two Britain-based banks will be able to absorb the cost of the settlements.

According to Shore Capital analyst Gary Greenwood, the penalties are equivalent to around 9 percent of each company’s 2012 pretax profits.

“The certainty is clearly welcome and helps to draw a line under the situation,” Greenwood said. “In terms of knock-on effects, we think it is likely to lead to higher ongoing compliance costs and perhaps some minor loss of business in the U.S., but nothing that will be particularly material to either company.”

Money laundering by banks has become a priority target for U.S. law enforcement. Since 2009, Credit Suisse, Barclays, Lloyds and ING have all paid big settlements related to allegations that they moved money for people or companies that were on the U.S. sanctions list.

Information for this report was contributed by Christina Rexrode of the Associated Press.

Front Section, Pages 1 on 12/12/2012