LITTLE ROCK — The head of the Pulaski County Special School District said he believes his school system can meet most of the requirements of its desegregation plan quickly.

But Superintendent Jerry Guess said one area might be a problem: finding enough money to renovate school buildings to meet federal court approval.

Guess’ comments during an interview Friday were his first public responses to a Dec. 28 decision by a federal appeals court that found that the district had failed to comply with nine provisions of its desegregation plan, including facilities, the student assignment plan, student achievement and student discipline.

The appeals court also found lacking the district’s Advanced Placement and gifted education programs, special education, scholarships, staffing and in-house monitoring of desegregation efforts.

As a result of the order from a three-judge panel of the 8th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals at St. Louis, desegregation efforts by the Pulaski County Special district will continue to be monitored by the federal courts for the foreseeable future.

Conversely, the Little Rock and North Little Rock school districts have been released from court supervision in the 29-year-old desegregation lawsuit.

All three districts, however, remain parties in the lawsuit and receive about $70 million a year in state desegregation aid payments that other districts in the state do not get.

Document set

School districts takeover and desegregation

- Consent judgment in Pulaski County desegregation case

- Defense of legal fees in desegregation lawsuit

- State objects to legal team's request in desegregation case

- Court: Desegregation office will close June 30

- U.S. District Court receives responses to proposed settlement

- City of Sherwood objects to deseg settlement agreement

- Sherwood ed group objects to deseg agreement

- Little Rock Chamber voices support for desegregation settlement

- NLR resident objects to proposed deseg settlement (3)

- NLR resident objects to proposed deseg settlement (2)

- NLR resident objects to proposed deseg settlement

- Stipulation by Joshua Intervenors and PCSSD regarding unitary status

- Updated draft of school desegregation lawsuit settlement

- "Transitional agreement" between PCSSD and Joshua intervenors

- Desegregation settlement draft outline, November 2013

- LR school district appeals charter school ruling

- Feb. 1 status report on Pulaski County Special School District

- Report concerning one-race classrooms

- LRSD response to ADE's motion for release

- Building fund projects numbers

- Judge's ruling on charter schools in desegregation case

- Judge's ruling for hearing in payment case

- PCSSD's memorandum in support

- PCSSD's motion for discovery order

- Judge denies PCSSD motion

- NLR schools declared unitary

- Joshua brief in support

- Joshua brief in support

- PCSSD Response

- NLRSD Response

- Brief in support of PCSSD response

- LRSD brief in support

- LRSD motion to dismiss

- Brief in support of NLRSD response

- Kimbrell's Letter

- Motion for release from settlement

- Brief in support of state

- State's Response - 3/12

- Response to facts - 3/12

- Charter Motion - 3/12

- Brief in Support

- ADE Response

- Desegregation Filing - Feb 14

- Desegregation Facts Filing - Feb 14

- Desegregation Motion Support - Feb. 14

- North Little Rock deseg documents filed in St. Louis - July 26

- PCSSD deseg documents filed in St. Louis - July 26

- Joshua Intervenor's Motion Persuant to Rules 52 (b) and 59 (e) - July 22

- Joshua Intervenors' motion filed July 22

- Joshua Intervenors' memorandum - July 22

- Joshua Intervenor's memorandum in support of motion

- Joshua Intervenor's memorandum in support of motion - July 22

- Joshua Intervenor's memorandum in support of their Rule 62.1 motion

- Desegregation case - Judge Marshall agrees not to recuse

- LRSD's brief on recusal issues in desegregation case

- NLRSD's response to recusal in desegregation case

- Desegregation case - State's response to recusal order

- Intervenors' response to recusal order - PCSSD desegretation case

- PCSSD Recusal Comments - Jacksonville

- LRSD v. PCSSD, Reply to Responses to Motion for Order

- June 19 2011 Letter from David Newbern to Dustin McDaniel

- PCSSD Financial Statements with report of accountants for June 30, 2008

- PCSSD Financial Statements for June 30, 2009

- June 10 Letter from ADE to Charles Hopson

- Letter from ADE to Charles Hopson

- Investigative Report Update #1

- Report of Independent Certified Public Accountants

- Letter from ADE to Charles Hopson

- Investigative Report Update #2

- Letter from Dept. of Education to PCSSD

- May 14 Investigative Report

- PCSSD response to recusal order

- PCSSD memo June 30

- Joshua Intervenors brief

- PCCSD Audit Part 1

- North Little Rock School District's brief in response to show cause order

- Little Rock School District's brief in response to show cause order

- Statement from John W. Walker

- PCCSD Audit Part 3

- PCCSD Audit Part 2

- Act 1467

- Letter from Tom Kimbrell to Willie Williams

- Letter from Tom Kimbrell to Vandell Bland

- Helena-West Helena School District audit

- PCSSD dissolved - School District's brief

- Elliot-PCSSD Lawsuit

- PCSSD dissolved - State's brief

- Joshua Intervenors' response to show cause

- Districts in fiscal distress

- Desegregation: 8th circuit filing response by state

- Desegregation: 8th circuit filing by LRSD Part 1

- Desegregation: 8th circuit filing by LRSD Part 2

- PCSSD dissolved - Motion for Order

- PCSSD response to motion for stay

- Desegregation state response

- Desegregation order denying stay pending appeal

- Desegregation response motion

- Joshua Intervenor's memorandum in support of motion for stay

- Motion for construction, reconstruction, consolidation

- Brief in support of motion

- Proposed Zone Changes — Jacksonville Elementary

- Letter about school facilities

RELATED

http://www.arkansas…"> Desegregation in Pulaski County

“I can promise you that in eight areas, we believe we can satisfy the deficiencies and we believe we can do that rather quickly,” said Guess, who is the state-appointed superintendent of the 17,637-student district, the third-largest in the state.

But, he said, the district - which has been classified as “fiscally distressed” and was taken over by the state in June - doesn’t have the money to do all he would like to do to improve school buildings.

“We are going to improve facilities,” Guess emphasized, saying there will be up to $4 million available for that work.

“The question is whether we can improve facilities to the extent necessary to satisfy the guidance of the desegregation suit.”

AFFIRMED LOWER COURT

In its ruling, the 8th Circuit panel upheld the findings of a May 19 decision by U.S. District Judge Brian S. Miller, who has since stepped down from the case and who has been replaced by U.S. District Judge D. Price Marshall Jr.

The appeals court panel found little to quibble with in the portion of Miller’s sternly worded order dealing with the Pulaski County district, which includes the Chenal Valley section of Little Rock; western, northern and southern Pulaski County; and the towns of Maumelle, Jacksonville and Sherwood.

“The district court relied in large part on evidence of PCSSD’s lack of good faith, finding at the outset that ‘it seems [PCSSD] has given very little thought, and even less effort, to complying with its desegregation plan. Complying with its plan obligations seems to have been an afterthought,’” the 8th Circuit panel decision said, quoting from Miller’s order.

“We find no reason to disagree with the district court’s observation,” the appeals panel added.

The Pulaski County Special district had argued to Miller and to the 8th Circuit panel that while the district failed to perform some of the tasks it committed to do in its desegregation Plan 2000, statistics showed that conditions in the district regarding staffing, student discipline, gifted education, special education and student achievement were comparable or betterthan in districts declared unitary (in compliance), namely the Little Rock and North Little Rock districts.

The appeals court panelrejected that argument, calling it “misguided.”

“We reemphasize that a constitutional violator seeking relief from a desegregation plan adopted as a consent decree must show both that it ‘complied in good faith with the desegregation decree since it was entered’ and that ‘the vestiges of past discrimination ha[ve] been eliminated to the extent practicable,’” the 8th Circuit panel said, quoting from an earlier court decision on school desegregation.

CHANGES UNDER WAY

Guess said Friday that the courts relied on testimony presented to Miller in a hearing in early 2010, nearly two years ago.

“There’s been a lot of things that have been done differently since that testimony was given,” Guess said.

One of the changes is the state is in direct control of the district.

Seth Blomeley, a spokesman for the Arkansas Department of Education, acknowledged that the state has a significant role in getting the district into compliance with its plan.

He said in an e-mailed response about the 8th Circuit order that the state Education Department has been “taking our job seriously in overseeing the school district, and that includes working to make sure the district’s desegregation plan is followed.”

The Pulaski County Special district’s former superintendent, Charles Hopson, who was displaced after one year of service as a result of the state takeover, said the 8thCircuit order “vindicated” his work in the district.

That work, he said, included the development of a comprehensive school facility improvement plan and the hiring of a consulting firm, thePacific Educational Group, to aid in eliminating discrimination in special education and other areas of district operations.

“The PCSSD desegregation plan was my single playbookduring my one year in the district,” said Hopson in an e-mail from his home in Portland, Ore. “It was nothing more than a systemic equity plan.I knew if we got the facility plan [approved by the state Education Department] and showed a sustained systemic effort with Pacific Educational Group focused on eliminating racial disparities cited in the plan, we were home free to unitary status within two years.”

Hopson said his efforts, however, were hindered by Jacksonville leaders who wanted a separate Jacksonville school system and by state legislators who were focused on past business practices in the district.

Guess said he and his staff, including Brenda Bowles, the district’s assistant superintendent of equity and pupil services, are addressing the areas of noncompliance.

“I think we have a lot of things going on to address the eight areas. We are working really hard under [Bowles’] experienced direction to meet the expectations that we should meet,” he said, noting as an example that the district will begin awarding scholarships to selected students as envisioned in the desegregation plan.

“The only area that I’m very concerned about is the school facilities. We don’t have the money at this point that would allow us to do some of the things we would like to do,” Guess said.

FACILITIES A CONCERN

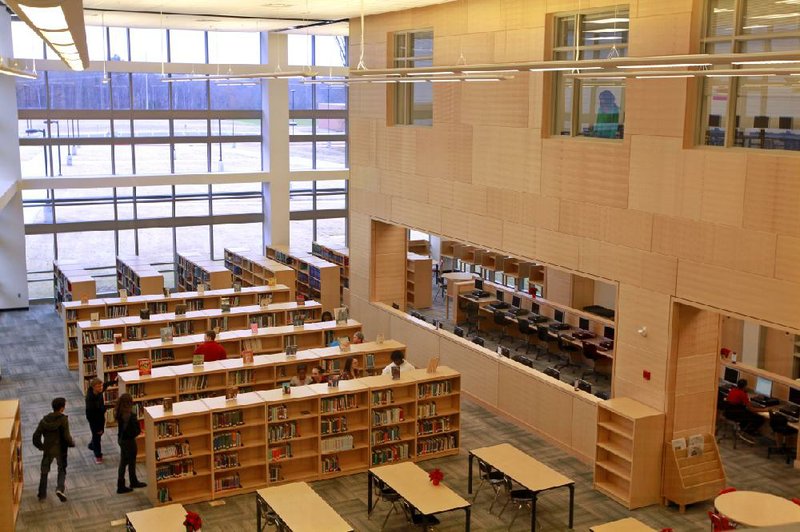

The 8th Circuit said it could find no clear error in Miller’s finding that the district devoted a disproportionate share of its spending on facilities in recent years to schools in predominantly white, affluent communities.

Those schools included the new Maumelle High and Chenal Elementary, and the new wing at Pine Forest Elementary in Maumelle. That work was done while older schools in predominantly black communities in the Pulaski County district “languish[ed] in relatively poor condition.”

The appeals court also said the lower court’s findings on facilities demonstrate an absence of good faith on the part of the district.

Guess said he and his staff anticipate that there will be as much as $4 million in the district’s building fund, some of which can be used to upgrade schools.

A list of the repair and renovation needs is being developed, and the items on it will be prioritized based in part on how each will help the district conform to the desegregation plan requirements.

District leaders plan to announce in the next few days a date for a district-sponsored public forum on school building needs.

Guess said the courts’ observations and findings are valuable.

“We now understand exactly what we need to do to erase those final vestiges of segregation to the extent that we practically can. That is our goal, and I am one who believes that we should be working tirelessly to do that,” said Guess, who as superintendent in the Camden-Fairview School District helped lead that system to be declared unitary.

In its ruling, the 8th Circuit panel addressed the lack of compliance in each area of the district’s plan.

SINGLE-RACE CLASSROOMS

In the area of student assignment, for example, the Pulaski County Special district was required to assign students in such a way that almost every school had an enrollment that was at least 20 percent black and, at the same time, didn’t exceed a maximum cap.

The district also had to prepare reports on the number of one-race classrooms in district schools, and describe steps considered to eliminate them and why those steps weren’t feasible.

In his ruling, Miller found that a number of the required reports on single-race classes were missing and others did not include the necessary details. The school system argued that very few students were affected by the single-race classrooms and that single-race classes occur because some elective classes are selected largely by white students.

That’s beside the point, the 8th Circuit countered.

“The parties’ agreement in Plan 2000 ... contains no reporting exceptions for such cases. It is not clear to us how PCSSD’s opinion that the explanations for single-race classrooms are non-discriminatory would excuse PCSSD’s failure to produce the plain and simple reports expressly required by Plan 2000.”

The 8th Circuit rejected the county district’s request that the two areas of student assignment - the one-raceclassrooms and the student assignment to schools - be separated and that the district be declared unitary in regard to the overall student assignment plan.

“Under the circumstances, the release of judicial control over the sub-area of assignment of students to schools would not be conducive to achieving compliance with at least one other facet of the decree, the sub-area of reporting on single race classrooms,” the 8th Circuit wrote.

“In addition, PCSSD’s dismissive approach to the onerace reporting requirement has done nothing to ‘demonstrate to the public and to the parents and students of the once disfavored race, its good-faith commitment to the whole of the court’s decree,’” the court wrote, citing desegregation requirements set in an earlier court decision.

In the area of Advanced Placement and gifted education, the district had proposed steps to achieve greater enrollment of black students in those courses, but the courts found that the enrollment goals were not met at most schools and that the district failed to show that it had carried out the promised recruitment strategies.

The district argued that the black-white enrollment disparity in the gifted andAdvanced Placement courses was less than that found in the North Little Rock district, which had been declared unitary.

“Unfortunately, mere comparisons to other unitary districts are insufficient to satisfy Freeman,” the 8th Circuit wrote, referring to the requirements set in the Freeman v. Pitts desegregation case involving the DeKalb County, Ga., schools.

“Because PCSSD has not even attempted to implement its plan, we have no basis on which to decide if the ‘vestiges of past discrimination ha[ve] been eliminated to the extent practicable’ at PCSSD,” the 8th Circuit said, again citing the Freeman case.

“More importantly, PCSSD, an adjudged constitutional violator, has done nothing to assure the public of any permanent good-faith commitment to promoting racial diversity in its Advanced Placement courses,” the appeals panel said.

The 8th Circuit similarly upheld the lower court finding regarding student discipline. The lower court said the school system didn’t make specific efforts to work with teachers and schools with racially disparate discipline rates. Nor did the district do a study on the issue of discipline and black male students.

In regard to special education, the district said it would identify and work with schools in which the percentage of black students identified as needing special education exceeded the school-wide black enrollment by more than 8.3 percentage points.

The lower court found, and the 8th Circuit concurred, that multiple schools failed to satisfy the 8.3 percent standard, but the district did not develop plans to assist those individual schools.

On the issue of staffing, the district continued to focus on outcomes, arguing that the percentage of administrators and staff members who are black exceeded the percentage in the relevant labor market who are black.

“[O]utcomes alone are insufficient; PCSSD must also show that ‘it complied in good faith with the desegregation decree since it was entered,’” the 8th Circuit said, citing the Freeman case.

In regard to student achievement, the 8th Circuit said the district failed to prove that it had complied with the obligation of its desegregation plan to design, select and implement specific intervention programs to decrease the achievement gap between black and white students.

Front Section, Pages 1 on 01/08/2012