LITTLE ROCK — On one level, comics are so much greasy kid stuff, cavity-inducing bubble gum for the mind. But look again and you can see the potential of the picture and text matrix, its inherent economy and power.

Comics might even be considered a static cousin to the movies as they tell their stories primarily through visual images, with language filling a supporting role. In cinematic grammar, the basic unit is the shot, which is such a perfect correspondent to the comic panel that a comic book could be used to storyboard a film.

Under these circumstances, it’s difficult to understand why there haven’t been more great films made from comic books and graphic novels.

Until you consider the respective audiences for Hollywood movies and comics.

Movies are mass entertainments, churned out by nuance-obliterating corporations intent on capturing every possible cent of revenue. Most comics readers - especially adults - belong to a species of detail obsessed fetishists. They are deeply invested in the imaginary worlds their heroes inhabit; they know the convoluted back-stories and the attendant trivia because this trivia - the accumulated, agreed-upon facts of the myth - isn’t trivial. It’s the essential stuff.

Here’s the problem any movie made from a comic faces: How can a comic encrusted with 20 or 40 or 60 years of arcane yet integral specifics be rendered in ways consistent with the Hollywood blockbuster while not overly offending the small but necessary core audience of hobbyists?

As I’m writing this, I haven’t seen the latest Batman movie, Christopher Nolan’s The Dark Knight Rises. I don’t know if - as rumored - Batman dies in that movie. But even if Nolan killed Batman, he won’t stay dead. There used to be a saying that the only people who stayed dead in the comics were “[Captain America’s sidekick] Bucky,[Batman’s second Robin] Jason Todd and [Peter “Spider-Man” Parker’s] Uncle Ben.” But Bucky and Todd were resurrected in 2005, and Uncle Ben lives on in some versions of the Marvel universe.

I was briefly enamored of comic books, maybe briefly obsessed. They cost 12 cents at the newsstand in the strip mall just outside the main gate of the air base where we lived. That was not an insurmountable barrier to ownership. All you needed to do was to hunt up three abandoned Coke bottles and collect the deposit at the gas station. Then you could ride your bike to the newsstand and convert your nickels to an issue, receiving 3 cents in change.

A comic-book hero’s claim on our attention arises first from aspiration - we tie a beach towel around our neck and jump off the roof, hoping to fly like Superman. We inevitably fall and, if we are lucky, learn something about our limitations.

Reading comics, I sometimes got the feeling the books were more meant for the young airmen we sometimes encountered in the store, often in T-shirted mufti, or for the middle-school boys who loitered in the bowling alley parking lot. I was better able to identify with the sidekicks - I named my first pet, a Dalmatian puppy, after Captain America’s doomed apprentice Bucky, and I fantasized about fighting crime as some kind of boy wonder rather than as an adult.

I always liked Batman better than Superman because he didn’t have the advantage of superpowers. He was rich, athletic and moralistic. I had the feeling that there was something deeper - that there was a code I couldn’t quite crack. But I was too young; another year or two, I might have become truly hooked. I was able to give up comics relatively painlessly and accepted the TV version - Adam West and Burt Ward as Batman and Robin - without reservation. I was as deaf to high camp as I was to insinuations of early Silver Age artists, whose Batman was the one I first encountered. These Batmen were lighter and sillier than the creature Bob Kane and Bill Finger created.

To suggest Batman began as a Jungian trope, a dark knight of the soul beating black wings in the shadows of the subconscious, is to overreach. He was born as a commercial venture, a Gimbels conjured up to oppose the Macy’s of Krypton - Action Comics’ Superman - who arrived in 1938 and became an instant pop hit. Vincent Sullivan was the editor of Detective Comics and he wanted a clone.

So he called in Kane, already a veteran comic artist at 18 years old. Kane went home and thought about Chester Gould’s Dick Tracy strip and the flying machine drawings of Leonardo da Vinci. The 1930 movie The Bat Whispers - about a murderer who wears a cape and shines a bat insignia on the wall before striking - also may have figured in his calculation.

With the help of his partner Finger, Kane came up with a becowled character he called Batman, a vulnerable, mortal earthling without superpowers who had trained his body and mind to fight crime. Later they contrived the back-story that Batman was in daylight hours a millionaire named Bruce Wayne whose parents had been murdered while they and young Bruce were walking home from a theater.Bruce took on the persona of Batman after dark, employing the costume as a psychological weapon against the “cowardly and superstitious” criminal mind.

I never knew the darkness of the original until director Frank Miller’s Reagan-era deconstruction of the myth, Batman: The Dark Knight Returns appeared in 1986. Miller’s Batman was sick, his grim pathology one of revenge. He did not murder, but he meant to inflict as much pain as possible on the lawbreakers he punished. Miller gave him a sidekick, but - perhaps mindful of the homoerotic undertones of the Batman and Robin dynamic - his Robin was a young woman in the mold of a gymnast like Mary Lou Retton.

(For more on the subject of Batman and Robin’s sexual orientation, see my blog - blooddirtangels.com.)

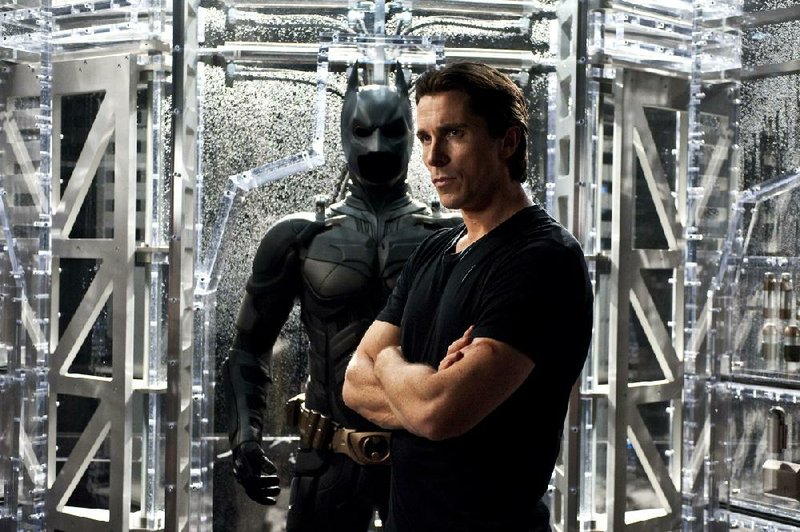

Strip away the Biff! Bang! Pow! and Wayne is revealed as a deeply unhappy man. What you realize as an adult is that masks and alter egos are accouterments of a bifurcated soul: Every superhero is a house divided against itself.

The unmasked face is nearly always the more interesting one, although Jung decreed that Superman was the real personality and that Clark Kent was but “a shadow.” Which makes sense considering that Superman was an alien being who had the Kent persona thrust on him by his adoptive Earthling parents.

While there’s no discounting the Biff! Bang! Pow! appeal of the character and the stories, the more interesting part of Batman has always been his alter ego - or, more precisely, the place where Bruce Wayne overlaps with his creation. There is something surpassingly strange about such a spooky, theatrical vigilante man.

E-mail:

Style, Pages 45 on 07/22/2012