FAYETTEVILLE — The whole history of epistemology - that is, the history of everything we know - has witnessed two monster paradigm shifts: the first, the mass production of books; the second, the mass production of bytes.

In 1999, well into the second paradigm shift, Washington Post columnist Joel Achenbach asked, Is anyone getting any wiser?

In a piece called “The Too-Much-Information Age,” he wrote that in 1472 the library at Queens College in Cambridge, England, had exactly 199 books.

It’s reasonable to think a few people in that college town probably had read everything in the world. At least, their world. The Western World.

Today it would be a surprise indeed if anyone had read the entire contents of the library in Reading, Pa., or Booker, Texas.

In Arkansas, just in the last decade, historians and philanthropists from every corner of the state have come together to create the Encyclopedia of Arkansas History and Culture, a searchable website that went online in 2006 with 700 subject entries and has become the single grandest, most popular source of our state’s history ever, standing in at 3,000 entries composed of 2 million words that, if it were a book, would sit a stout 4,000-book-length pages excluding images and graphics.

Meanwhile, at the University of Arkansas at Fayetteville, another smart set chips away at a very different electronic index of Arkansas history, one still more ambitious than an encyclopedia.

HIS STORY AND HERS

The David and Barbara Pryor Center for Oral and Visual History actually predates the encyclopedia by several years. It began in 1999 when the former governor and U.S. senator bequeathed his leftover campaign war chest - $220,000 - to the university for the project. The first interview was recorded by history professor Jeannie Whayne with a cassette tape recorder.

Today, the center’s paid staff of five (the encyclopedia’s is seven, full- and part time) goes to work in the field as much as 20 weeks each calendar year. In place of tape recorders, they carry full production sets by rental truck - big tungsten floodlights and a four-channel mixing board, Sony HVR-Z1U studio cameras and boom microphones. In place of an analog cassette, it’s all saved to a pair of 1-terabyte hard-drives the size of a paperback Catcher in the Rye.

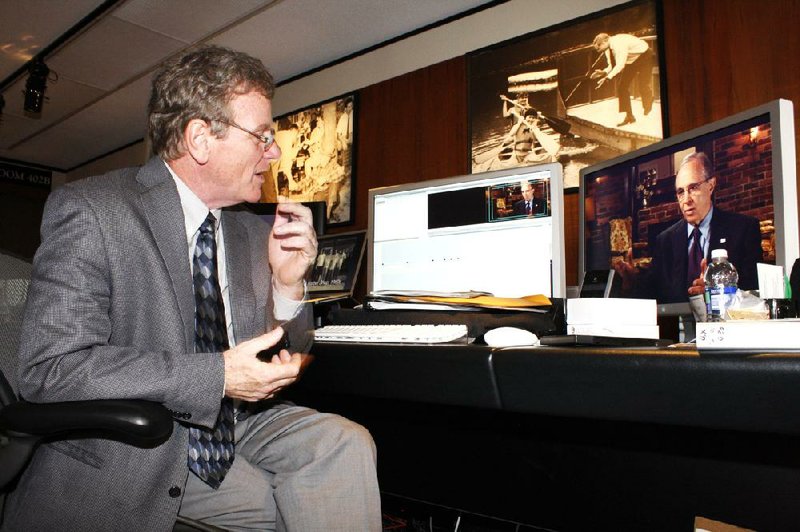

When it’s done, they return to the offices inside Mullins Library. They pull the video up on side-by-side 31-inch Apple monitors that make the faces larger than life, literally, and edit for sound and video interruptions but not for news value - they don’t cut the interview. It’s all there. This isn’t for broadcast, it’s historical material.

All told, the staff collects about 50 interviews a year. Volunteers contribute another 100. The center has collected nearly a thousand interviews, about a quarter of those in high-definition video.

One of the earliest projects was interviews with former employees of the Arkansas Gazette and Arkansas Democrat newspapers. Longtime reporter and professor Roy Reed drew on about 150 of the interviews for his book Looking Back at the Arkansas Gazette: An Oral History, published in 2009. Longtime reporter and editor Jerry McConnell is culling another 120 interviews for a companion tome about the Democrat he hopes will be published in about a year.

All of the interviews can be read in their entirety on the website, pryorcenter.uark.edu.

“Since these interviews a whole gang have died,” Reed says. “I sensed that these people had a lot of memories that would be lost. Memories of not just old newspaper guys ... but stories they’d covered, people in the government, governors, scoundrels.”

HISTORICAL CAPITAL

There are two origin stories for the Pryor Center. One goes: In the wake of the Clinton-Lewinsky scandal and the lingering suspicion that America considered the state a low country colonized by rubes and country boys, the senator wanted to start a cultural renaissance promulgated by Arkansans, folks who would set the record straight with Bear State style.

Well, that story just ain’t true, Pryor says.

It was at a reception in 1999 for “one of my mentors,” the late Sen. Russell Long, that Sen. and Mrs. Pryor visited the campus of Louisiana State University and its oral history program.

“Driving back, I said, ‘Barbara, why can’t we have something like this that will help us preserve our history?’ Because all these people that made Arkansas significant are passing away.

“I picked up the paper today, and I knew four people, four names of people I knew who’d passed away.”

There’s “a hunger” for old stories and good storytellers, authentic cross-generational exchange, he says.

There’s also a growing economy surrounding oral history and primary source material.

Pryor sits on the board of the Corporation for Public Broadcasting, which governs National Public Radio and the Public Broadcasting System, and he says public radio’s Story orps project has grown to seven traveling mobile interview studios that cross the country gathering first-person accounts. Meanwhile, he says, the corporation is gathering up the libraries of local and regional broadcast stations, like AETN, for storage in a national archive somewhere in the country.

It may be that sometime in the future 60 Minutes or HBO will pursue a documentary on some element of Southern heritage, and they’ll seek out the production equivalent of a one-stop shop for audio and video archives, says Pryor Center Director Kris Katrosh, and perhaps they’ll choose Arkansas as a representative Southern state over Alabama because of the resources the Pryor Center has accrued.

“What if all this American, this Southern, this Arkansas history was available to everyone? Maybe we’d have more Arkansas history in the Oxford American. Well, we’d certainly have more Arkansas history in the Oxford American.”

WHAT OF ALL THESE BYTES?

But what of all these histories - all these bytes?

No one has read all the material inside the public library in Reading, Pa., but no one would deny that the pursuit is an edifying one. Noble, even.What about all the Tweets ever posted to the social networking site Twitter? In 2010, the Library of Congress began archiving every Tweet ever made, and not just from that moment forward but retroactively, since Twitter went online in 2006.

In library science there’s a working notion that only a small percentage of large library holdings circulate more than once a year. In a library such as the one at our flagship university, many more books and documents are preserved in climate-controlled stacks than anyone has a mind to use.

“Our collection is more than a hundred years old, so yeah, there’s stuff we don’t circulate. Nobody calls for it. It might be out of date,” says Judy Ganson, director for collection management services and systems.

On the other hand, who should decide a material’s worth? And, isn’t it fluid?

One of the more popular stores inside University of Arkansas Libraries Special Collections is the papers of George Fisher, the longtime political cartoonist, though Ganson couldn’t specify the use rate.

“What we’re doing today will be history tomorrow,” she says. “Those people [interviewed by the Pryor Center] were here in the state at a given time when important things were taking place, and having their perspective is important to historians, sociologists and just kids who grew up in the area.”

WHAT’S NEXT FOR HISTORY

From a $220,000 gift, the Pryor Center began. It got a massive investment in 2005 when the late Don Tyson made a $2 million gift to the center, $1.2 million for an endowment and the rest for equipment and operations.

Today, the center operates on an annual stream of about $150,000 from the university - public funds - and perhaps twice that much in private donations.

In May, university administrators announced an agreement in principle to purchase most of the East Square Plaza building on the Fayetteville square. It’s to be the new home for the Pryor Center and the Community Design Center.

The center aims soon to buy an RV or large trailer for mobile shoots, much in the model of NPR’s StoryCorps.

Meanwhile, Katrosh has been partnering with education professor Dennis Beck to design middle school curricula around the Pryor Center’s online archives. One sample lesson asks students to view Dale Bumpers’ interview excerpts and discover what role his family played in his early ambitions and what obstacles he faced. Another lesson asks students to make the case in a letter to their congressman that Dr. Edith Irby Jones deserves the Congressional Gold Medal.

In 2009 Pryor helped negotiate the transfer of a huge stock of Little Rock station KATV, Channel 7, film tapes to the Pryor Center, footage going back to the 1929 Hope Watermelon Festival, The Beatles at Memphis’ Mid-South Coliseum in 1966 just days after John Lennon boasted the band was “more popular than Jesus,” Little Rock’s biggest fires, the missile silo explosion near Damascus in 1980.

“It’s all first generation, too. That’s what’s awesome about it. The film has such a different look, such a saturation,” says Randy Dixon, project archivist. “It’s very clear. It’s very clean.”

Dixon has been posting snippets of the archives to the Pryor Center’s Facebook page (Facebook.com/pryorcenter). Earlier this month, during the Miss Arkansas pageant, he posted the crownings of Paula Montgomery in 1995 and Regina Hopper in 1983.

Within two years Katrosh hopes to coordinate the creation of an index for searching specific video and transcript segments by keyword. It will be the first in the nation to have such an interface, he says, and it will put the Pryor Center in a position to match the popularity of the Encyclopedia of Arkansas, which today attracts about 100,000 visitors a month.

“Our goal is to make it where anyone who wants any specific video clip or audio clip can, with four or five clicks of a mouse, or a few keywords, find it” from their home computers, Katrosh says. “If you want people to use an oral history project, it has to be just that easy.”

It has to be that easy because information nowadays is that easy - material that is not online and “searchable” increasingly falls into disuse, obscurity.

That doesn’t sit well with Whayne, who says the search engine trend is anathema to historians and historical research.

“Because I know [my students] are going to miss things I haven’t asked them to look for. It’s that process of poring through the primary documents where one is truly enlightened.”

No matter its advancements, the center will continue to be an old-fashioned repository. That is, a collection of storytellers.

“You sit down to write a [history] with stats and government reports and newspapers - those are valuable sources, but you ... want to tell a story, you have to go to the human beings,” Whayne says. “What people are saying and from what perspective. Without that, it’s just dry bone.”

Style, Pages 47 on 07/29/2012