LITTLE ROCK — After a genocide in Rwanda that left nearly 1 million people dead and about 200,000 people accused of committing and orchestrating violent crimes, the African nation faced “the biggest judicial challenge in legal history,” a government leader said in Little Rock on Monday.

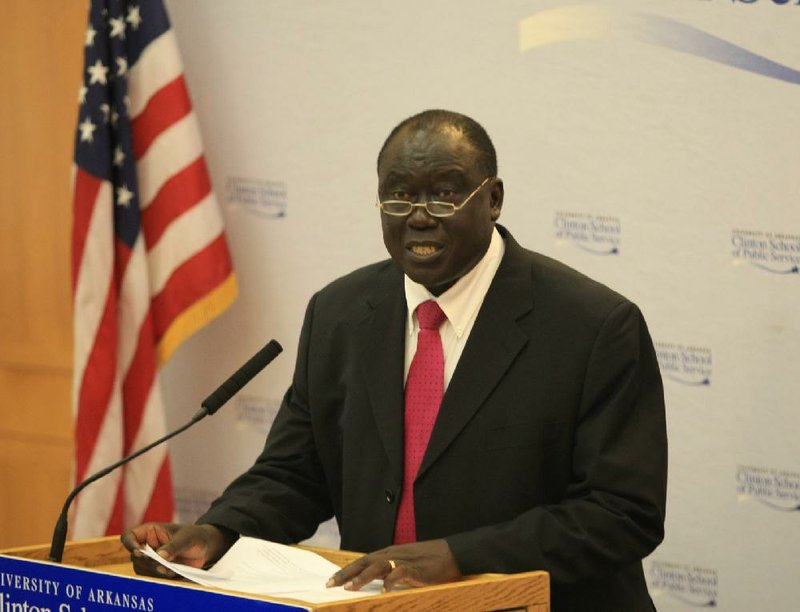

Leaders struggled to gain justice for victims of the 1994 rape and killing rampage while also preserving justice for the accused, offering timely trials to avoid unsupported incarceration, said Tharcisse Karugarama, the minister of justice and attorney general.

“We were a country of stench and rot, a country where there was no hope for the next day,” he told an audience at the University of Arkansas Clinton School of Public Service while describing dead bodies decomposing in bushes and prisons packed with the accused.

But a weak judicial infrastructure and a lack of judges, investigators and attorneys meant that trying the cases in a “traditional Western style” would create a bottleneck, drawing out the process for years and years, Karugarama said.

“Everyone wanted justice, but no one had a formula,” he said.

After years of working to quickly train judges and lawyers, the country turned instead to a modified community-justice system called “Gacaca.”

Under the system, previously used to resolve tribal disputes, victims confronted representatives for the accused before a panel of elected community leaders without attorneys or trained judges.

The process offered leniency in exchange for a confession, replacing half of a prison sentence with community service for those who admitted to committing crimes, Karugarama said.

“Without the participation of the perpetrators of genocide, the truth would have never been known,” he said.

The resulting system — criticized by some civilrights advocates — has been “a miracle,” allowing for the trial of 2 million crimes since it began in 2002, Karugarama said.

Those trials were speeded by waves of Christian conversions in the prisons, leading many to confess, he said.

Gacaca courts were never intended as a permanent solution, he said. With the conclusion of genocide-related hearings, the country intends to close the Gacaca system in June, Karugarama said.

Critics of the system say it is difficult to provide fair trials without trained attorneys to protect the rights of victims and defendants.

Karugarama acknowledged some problems with Gacaca courts, but he argued there was no reasonable alternative to bring closure to Rwanda’s crisis.

“Justice is not about form but about substance,” he said. “Justice is about reconciliation. It’s about fairness. It’s about transparency. It’s about the truth.”

Scars remain in Rwanda, Karugarama said. But today, genocide victims peacefully work in fields next to men and women found guilty of killing their family members, he said.

And women widowed in the genocide have joined in support groups with women whose husbands are in prison for participating in their deaths, he said.

“Anybody can say, ‘This and this is wrong,’” Karugarama said. “But if you ask them what is right, they cannot give an answer.”

Arkansas, Pages 7 on 05/22/2012