PHILADELPHIA — Mitt Romney struggled to find support for his education proposals while campaigning at an inner-city school Thursday, one day after declaring education the “civilrights issue of our era.”

The visit, the first by the likely Republican presidential nominee to such a school, came as he begins to court a broader cross section of the electorate he needs to defeat President Barack Obama in November. In a speech Wednesday, the former Massachusetts governor proposed expanding charter schools, which are privately run but funded by taxpayers, and creating a voucherlike system in which poor and disabled students could attend private schools using public money.

But if praise was what he was looking for, Romney had a hard time finding any at the Universal Bluford Charter School in West Philadelphia, a largely black neighborhood facing economic, educational and social challenges.

Romney wants to deny a second term to the nation’s first black president, whose photograph hung in one of the school’s hallways.

During a round-table discussion, teachers and local education leaders rejected some of Romney’s education prescriptions, including his assertion that class size doesn’t matter.

Romney also identified two-parent families as one of three keys to educational success, along with good teachers and strong leadership.

Local education leader Abdur-Rahim Islam pushed back, telling Romney that two-parent families are unrealistic in the community.

“We will never get to that second part described about having a two-parent situation, parent support, as a key component,” Rahim said.

Steven Morris, a music teacher at the school, disputed Romney’s assertion on class size.

“I can’t think of any teacher in the whole time I’ve been teaching, over 10 years — 13 years — who would say that more students would benefit them. And I can’t think of a parent that would say, ‘I would like my kid to be in a room with a lot of kids,”’ Morris said. “So I’m kind of wondering where this research comes from.”

In response, Romney cited a study by the McKinsey consulting firm, which he said examined education systems in foreign countries and concluded that class size wasn’t a significant issue.

While he struggled to win over the group, Romney does not necessarily expect to do well in Philadelphia, a Democratic stronghold. Nor does the campaign expect to take a significant block of the black vote from Obama in what is shaping up to be a close election.

But coming off a divisive Republican primary that was dominated by staunch conservatives, Romney is eager to expand his appeal to independents and moderate voters in swing states like Pennsylvania, where Obama defeated his Republican opponent by 10 points in 2008.

The school visit was in line with the “compassionate conservative” push that Republican George W. Bush used to soften his image and win over moderate voters when he was elected president in 2000.

Outside the school, Philadelphia’s Democratic Mayor Michael Nutter, an Obama supporter, lashed out at Romney’s visit.

“It’s nice that he decided this late in his time to see what a city like Philadelphia is about,” Nutter said. “I don’t know that a one-day experience in the heart of West Philadelphia is enough to get you ready to run the United States of America.”

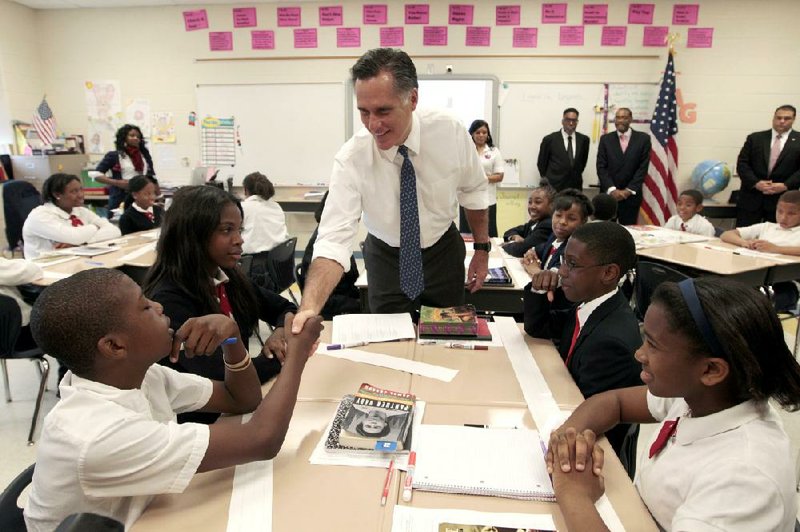

Besides discussing his policies with nearly a dozen local education leaders, Romney also visited with children. He shook hands with a classroom of thirdgraders and stood virtually motionless for several minutes, bobbing his head ever so slightly at times, as a music class sang and danced for him.

During the discussion, the school’s founder, Kenneth Gamble, told Romney that his “major concern is the future and the destiny of African-American people in this country. Because once that problem is solved, I think that all of America will benefit from it.” Romney said he agreed.

Asked afterward whether thinks Romney understands the black community, Gamble replied: “I don’t know yet.”

Meanwhile, Obama on Thursday accused Republicans in Congress of blocking initiatives to bolster economic growth and warned that the U.S. will lose jobs unless lawmakers extend clean-energy tax breaks.

Obama used the backdrop of TPI Composites, which makes structural components for wind-powered generators and employs about 700 workers in Newton, Iowa, to promote his list of economic measures that he wants Congress to act on.

The tax credits have had broad political support, according to the administration, from organizations including the Chamber of Commerce, the National Association of Manufacturers and the National Governors Association.

The White House said failure to renew them could cost as many as 37,000 jobs.

“This isn’t just an issue for the wind industry,” Obama said in the text of his remarks.

“Some of America’s most prominent companies — from Starbucks to Campbell’s Soup — are calling on Congress to act because they use renewable energy.”

The president was making his third visit to Iowa this year after wrapping up four fundraisers in a twoday swing to three states, collecting more than $2.5 million.

Iowa is one of nine swing states that was won by Bush in 2004 and switched to Obama in 2008.

Information for this article was contributed by Steve Peoples of The Associated Press and by Roger Runningen of Bloomberg News.

Front Section, Pages 4 on 05/25/2012