LITTLE ROCK — Dr. Robert Arrington has won numerous awards in his almost 40 years at Arkansas Children’s Hospital in Little Rock. The only prize he shows off is a photo that he carries on his cell phone.

The picture is a boy in hospital scrubs with a staff name tag on a cord around his neck. He is dressed up like a doctor for Halloween - like a happy doctor bringing good news.

“That’s me,” Arrington, 70, says, and his smile is the tip that he has a joke to spring. Nobody could smile this way better than a 12-times grandfather. The trick is in the photo’s explanation.

The toddler in the picture is Samuel Pope. And Samuel is not just playing doctor - he is playing Dr. Arrington, the man who made it possible for him to play at all.

“He was a very sick little boy,” Samuel’s mother, Sarah Pope, says.

She had to be airlifted from home in Bentonville to the University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences (UAMS) in Little Rock, where she gave birth to Samuel at 24 weeks into her pregnancy. Normal gestation is about 40 weeks.

Deprived of time to grow in his mother’s womb, Samuel came into Arrington’s care as a 1-pound, 9-ounce bundle of worries in the Neonatal Intensive Care Unit at Arkansas Children’s Hospital. The baby’s tiny lungs were too weak to sustain him, and he had other life-threatening problems internally.

Samuel’s 125 days of intensive care gave his frightened mother all the time she needed to see that Arrington was “really involved” in the case. The doctor took care of her and her husband, Michael, too, she says, making sure they understood the treatment.

“He would watch the [baby’s] monitors,” Sarah Pope remembers, “and I could almost sense there were so many things going on in his head, so many complications.”

“Dr. Arrington made such an impression on us,” she says. “He was such a big influence on Samuel’s outcome.”

Two and a half years after that rush to intensive care, his mother reports the boy’s condition is “excellent. He has no lasting medical problems. He is developmentally on track.”

Arrington pockets the phone as if to say in the gesture: What else is worth telling?

He is reluctant to sit down for an interview about his career and accomplishments. He would rather someone else receive the attention, he says by way of introduction. The “father of neonatology,” they call him, but he doesn’t.

The title he claims is professor of pediatrics and section chief of neonatology. Neo (new) and natal (birth) refer to newborns. Premature babies, the smallest, are Arrington’s specialty.

Section chief means double duty. Arrington oversees the nursery at UAMS, and the 100-bed intensive care unit at the children’s hospital.

“The babies here [in intensive care] are the smallest and have the most threatening illnesses to their lives,” Arrington says. For those who share the doctor’s faith, they are among the most prayed over. The Neonatal Intensive Care Unit treats from 700 to 900 such infants a year.

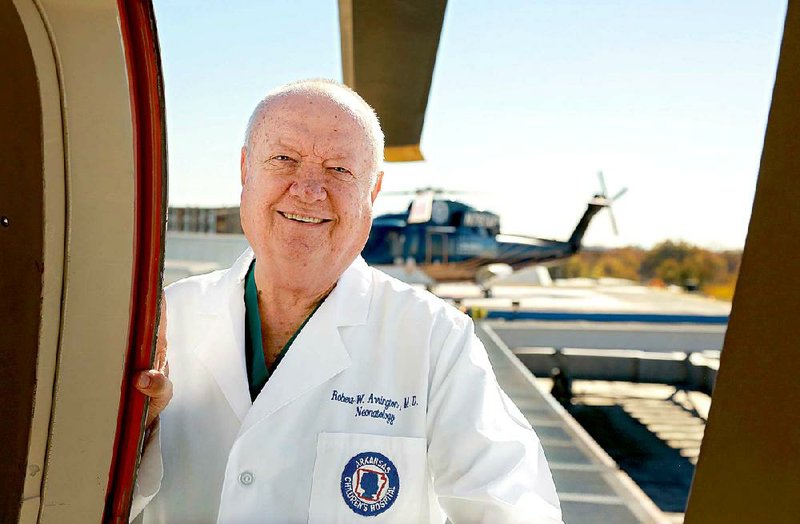

The doctor has experience. He has been section chief for 34 years. He has gold-rimmed glasses, steady eyes, a rim of silver hair. He has a backache but he doesn’t show it. He has science fiction-like technology. He has helicopters on the roof.

Up there, the two jet-fueled Sikorsky S-76C+ ’copters, the Angel Ones, await their next emergency transport mission. The wind sock catches the chilled breeze of a blue-sky day in November. And up there, he can survey the whole 28-city-block sprawl of Arkansas Children’s Hospital.

He points out the glimpse of old red roof that peeks from hiding, the least impressive thing to see. Newer, taller, glassier additions surround it, this red-roofed spot that was all there was to the children’s hospital when Arrington signed on.

Being for older children, not babies, the old hospital lacked even a nursery. Children arrived in ambulances made for grown-ups. Arrington pushed for a specially built van, made just for children.

“We put about 250,000 miles on it,” Arrington remembers. When it finally conked, he found out the company that made the vehicle, in New Jersey, had quit the business. The only other van similar to the one he bought, they said, tipped over.

The helicopters land near a double-door entry to the elevator to intensive care. Help is immediate. Change is constant. He imagines a medical futurist’s dream of liquid ventilators. Advanced antibiotics. No more troubled pregnancies.

But to say he has made even a pound’s worth of difference? - that he brought about today’s standard of neonatology in Arkansas? Arrington has a way of confounding people who try to praise him - a sudden new interest to talk about, NASCAR. And how ’bout them Hogs?

“I’m all for Arkansas,” the doctor says, “even the Razorbacks this year.”

Pinned to the subject of own achievements, his comment runs around the end:

“The way I’ve always viewed this job,” he says, “all this was going to happen.”

His knack is simply to have been around, the way he tells it - to have been lucky enough, maybe blessed enough, to be in the right place.

WELL, THAT’S BOB FOR YOU

“A more humble man I’ve never met,” says Dr. Richard Jacobs, chairman of the UAMS Department of Pediatrics, and director of the Arkansas Children’s Hospital Research Institute.

“‘Father of neonatology’ for Arkansas is a very accurate assessment,” Jacobs says.

This leaves the title of “mother” to Alice Beard, chief of neonatology at UAMS when Arrington trained there. He joined the UAMS Department of Pediatrics in 1974.

The field has advanced so much since then, Jacobs says, Arrington practically invented today’s level of care in his home state. Arkansas Children’s Hospital claims the state’s highest-level intensive care.

Even babies of less than a pound, even babies in need of heart surgery have a chance in this place that Arrington built up from a start of 15 beds to the current 100.

Dr. Whit Hall, Arrington’s colleague and fellow professor of neonatology, also gives Arrington credit for having had a hand in training almost all of his colleagues.

He “helped train most of the neonatologists who care for Arkansas’ sick babies,” Hall says.

“He helped usher in neonatal ventilation from its beginnings in the ’70s.

“He has gone to almost every hospital in Arkansas teaching neonatal resuscitation.”

Arrington says he took up baby care only because “I didn’t think I could be a family doctor for anything that might walk in the door. I didn’t think I could learn that much.”

People who know Arrington - call him “Dr. A” - don’t believe a modest word of the couldn’t-learn-so-much story he is fond of telling, Jacobs says.

“Really small, very, very complicated babies” depend on what Arrington knows, Jacobs says.

Such babies - babies like Samuel - had just a 50 percent to 60 percent chance of survival 20 years ago, the children’s hospital reports. Today’s rate is 80 percent to 90 percent. Research, better medicine, faster technology, many factors play a part in saving lives. But so does one doctor.

Jacobs and Hall say that doctor’s name is Arrington.

QUITE THE HANDFUL

This much, even Arrington can’t deny: That he looks to perfection like the guy who is going to make things right. The proof is framed on the wall. He is the doctor in the movie poster-like image near the entrance to intensive care, the doctor with the baby he doesn’t really need two hands to hold. The baby is small enough for one hand.

Beyond, posted at the nurses’ station, a child’s crayon drawing of a clown in striped pants tells the rest that a visitor needs to know: “Please be quiet. The children may be sleeping.”

In each case, something has gone terribly wrong in a tiny person’s first 28 days of life outside the womb.

Often, these babies have been thrust into the world much sooner than nature intended. Born prematurely, they just aren’t ready. Their skin is yellowed. Their systems aren’t working. They can’t breathe the way they should. They have been oxygen deprived. Their brains have swollen.

They can’t say how they feel. They can’t say what hurts. They can’t offer a clue to what ails them.

“Basic training is to learn to recognize what’s normal,” Arrington says. “Once you’ve taken care of hundreds, thousands of normal babies, it gets to be pretty obvious to you what’s not normal.”

The blue-and-white environment is old and new and “who knew” all at once - here, as sleek as Dr. McCoy’s sick bay on Star Trek; there, as soft and old-timey as Granny’s house.

Here: An oscillating ventilator, fluttering quick breaths to a baby with weak lungs.

There: A rocking chair such as might creak on the front porch.

Here: A temperature- and humidity-controlled Plexiglas incubator, clear as a jeweler’s showcase. The blue light on the wee patient inside is a treatment called phototherapy, to restore healthy skin color.

There: A quilted blanket, sewn and donated by hospital volunteers.

Blinking monitors keep watch. The baby’s mother keeps watch. The doctor knows which kind of sentry is the most constant, worries the most, hopes the most, cries the most, is likely to see the first sign of improvement.

“Mom’s been here the whole time,” Arrington says. A baby’s stay in the unit might be days, might be months. “A long line of mothers have got so wrapped up in this, they’ve gone on to nursing school.”

STEP RIGHT UP

Beginnings can be improbable, none more so than neonatal care. Some of the first nurseries for premature babies were sideshows - most famously, at New York’s Coney Island and the world’s fairs in Chicago and New York in the 1930s.

Carnival barkers touted the spectacle. A young Archibald Leach made his start in show business as a baby show barker, and went on to be known by his movie-star name, Cary Grant.

From these shows, “came the general idea that if you keep babies warm, they’re more likely to survive,” Arrington says. For the time, it was new thinking.

Arrington took nearly as implausible a route to medicine, having grown up the son of an agricultural researcher. His father’s job was to try to grow better peaches around Nashville, north of Hope.

Peaches, the boy learned, are delicate. He couldn’t imagine he would want to look after anything as small and dependent on the right care as a peach.

“It was not my intention to be a doctor,” Arrington says.

He enrolled at the University of Arkansas at Fayetteville to learn chemical engineering. But late one night, he had the sort of aha! moment that leads to big discoveries - or in his case, big doubts.

“Chemical engineering,” he decided, “was not as fascinating as I thought it would be.”

He was a third-year engineering student, winner of the outstanding freshman engineering student award (1961), and “well along” to a life’s work of making things out of chemicals. But here he was, 3 a.m., cramming for a test, when something made him wonder what to make of himself.

“I’m a Christian,” Arrington says. He held to the way he was raised, “and as I’ve grown in my faith and grown older, I think God has nudged me here and there to get me on the path where I’m supposed to be.”

This particular nudge came from a study partner’s comment that Arrington might be better suited to pre-med.

“I said, ‘What’s pre-med?’” Arrington remembers.

Be a doctor, the guy said, and Arrington thought it over. All night, he thought it over.Come seven in the morning, he says, “I called my parents and said I was going to medical school. They took it a lot better than I would if one of my children had done the same thing.”

Arrington and his church organist wife, Mary Kate, have four grown children - none doctors, no surprise announcements, but a 13th grandchild is on the way.

UP (LATE) AND AT ’EM

At so-called retirement age, Arrington still pulls his share of all-nighters. Doctors generally expect they will have to work around the clock now and then. But, still. Given his status at the hospital, somebody might cut him a little slack. Who’s responsible?

He is: He makes out the schedule.

“He never asks anyone to do anything he wouldn’t do,” Hall says. Working for Arrington, he adds, “I never felt I had a boss. I felt I had a partner.”

“I’ve got a bunch of hardworking, loyal partners,” Arrington says - about 25 doctors, 17 nurse practitioners on his staff. “I don’t do all this by myself.”

No, but he is the one right here, right now, standing by the incubator.

“I keep fit,” he says, “and I do that so I can keep working this schedule.”

He keeps faith for the same reason.

“Its not so much what I see that gives me faith,” the doctor says. “It’s the fact that I go in there with faith every day.”

SELF PORTRAIT Robert Arrington

DATE AND PLACE OF BIRTH Aug. 14, 1942, Fayetteville.

IF I HAD A NICKEL FOR EVERY BABY I HAVE HELD OVER THE YEARS, I WOULD BE WORTH $50,000. That would be a million babies.

MY ADVICE TO A NEW FATHER ON HOW TO HOLD A BABY IS They’re not as fragile as you may think, but if you do hold a baby, hold the baby securely.

HAVING 12 GRANDCHILDREN, MY SECRET TO REMEMBERING ALL THEIR NAMES IS It’s not hard. I have a pretty good memory. But I can’t remember their birthdays. My wife does that.

WHEN I’M THE PATIENT, THE KIND OF PATIENT I AM IS Compliant to a fault. I never miss a dose. I never miss an appointment. I’m a good patient.

THE ONE THING MY HOSPITAL NEEDS THE MOST RIGHT NOW IS I’ve thought for a long time we need a third helicopter.

FLYING IN A HELICOPTER FEELS LIKE (A) SUPERMAN, (B) SPIDER-MAN, OR (C) OTHER: Other. It’s a combination of excitement and fear.

THE BEST THING FOR A PERSON TO DO WHEN HE IS FEELING SCARED IS Exercise your faith.

THE LAST BOOK I READ WAS Battle for the Beginning by John MacArthur. It’s a defense of creationism, and I’m a creationist. I’ve read it over and over.

MY FAVORITE THING THEY SERVE IN THE HOSPITAL CAFETERIA IS Biscuits and gravy, unfortunately.

MY FAVORITE DOCTOR ON TELEVISION IS Marcus Welby, M.D. [Dr. Welby made his rounds almost 40 years ago, the last time Dr. Arrington remembers having time to watch TV doctor shows.]

A WORD TO SUM ME UP Loyal. I’ve been here 39 years. The day I started here, I told the boss, “I’m not going anywhere else.”

High Profile, Pages 37 on 11/25/2012