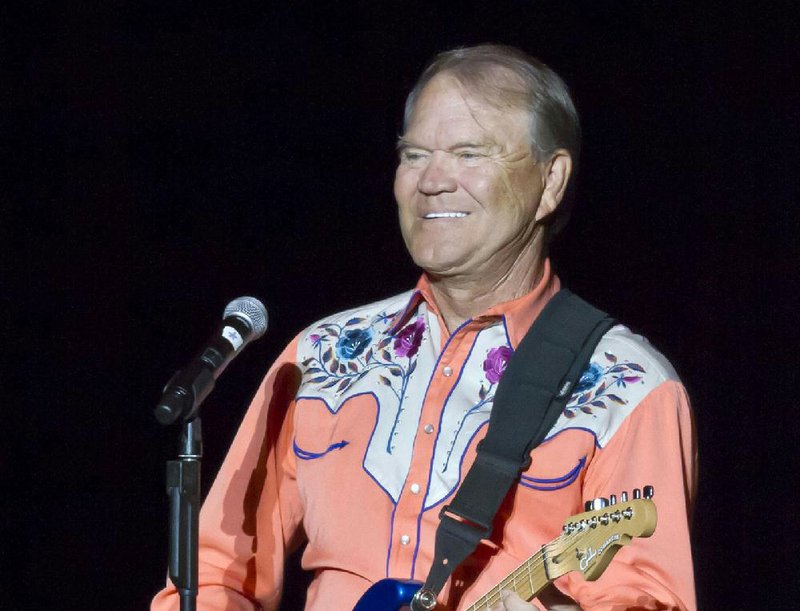

WASHINGTON - Her father, Arkansas native and music legend Glen Campbell, sat next to her at a Senate hearing Wednesday, but Ashley Campbell told lawmakers that the country and pop-music legend’s mind has begun to slip away.

Glen Campbell, the prolific performer and songwriter of hits, including “Rhinestone Cowboy” and “Wichita Lineman,” was diagnosed with Alzheimer’s disease in 2011. He undertook a farewell tour that was cut short in December, when he announced his retirement from performing publicly.

The singer, who was born in 1936 in the Pike County town of Delight, arrived in Washington on Tuesday to accept the Alzheimer’s Association Sargent and Eunice Shriver Profile in Dignity Award. On Wednesday, he pressed lawmakers to increase federal funding for Alzheimer’s research. It was his second time on Capitol Hill since being diagnosed with Alzheimer’s, a fatal form of dementia that causes memory loss, confusion, irritability and mood swings. This time, the singer smiled but remained silent, and his daughter spoke for him.

“Alzheimer’s robs you of your life when you are still living it,” Ashley Campbell said.

The Campbells and about 900 members of the Alzheimer’s Association fanned out across Capitol Hill offices Wednesday for meetings with legislators and their staffs. Dressed predominantly in purple and wearing purple sashes over their shoulders, they urged members to support $100 million in additional funding for Alzheimer’s research that was included in President Barack Obama’s proposed budget.

Ashley Campbell is a recent graduate of Pepperdine University in California. She said that since her father was diagnosed, she’s concentrated on her favorite memories with him, including going fishing in Flagstaff, Ariz., and playing the banjo with him accompanying her on guitar.

“Now when I play banjo with my dad,” she paused, “it’s getting harder for him to follow along,” she said, her voice cracking.

“And it’s harder for him to remember my name,” she said, her soft voice dissolving into tears.

She paused, then continued with her voice getting stronger, reaching every ear in the packed committee room.

“We need to find a cure for this,” she said. “So much pain should not exist in the world.”

Glen Campbell moved to Los Angeles in 1960 and worked regularly as a studio musician for stars that included Frank Sinatra and Merle Haggard. After a touring stint with the Beach Boys, he launched a solo career that took off when he popularized a John Hartford tune, “Gentle on My Mind,” a sweet, jangling ode to the memory of a former love. Campbell used that song as the theme song for The Glen Campbell Goodtime Hour, a weekly music and comedy show that aired for three years on CBS beginning in 1969.

The song concludes:

“I pretend that I hold you to my breast and find

that you’re waving from the back roads

by the rivers of my memory

Ever smiling, ever gentle on my mind.”

On Wednesday, the singer did not address the committee, but before the hearing, he serenaded lawmakers in a private committee anteroom in the Dirksen Senate Office Building. He sang two of his older songs, “Classical Gas” and “Lovesick Blues.”

“He didn’t miss a note,” said his manager, Stan Schneider, after Wednesday’s hearing.

“For Dad, music has been therapeutic,” Ashley Campbell told the panel.

Sen. Susan Collins, a Maine Republican, said Glen Campbell’s “guitar skills are second to none, and he still has that wonderful voice.”

In May, the Alzheimer’s Advisory Council, a group with the task of developing a strategy to fight the disease, will report on progress that is being made.

Ronald Peterson, the chairman of the group, said the National Institutes of Health spends less than $500 million a year on Alzheimer’s research. That’s not enough, he said, to stop the disease’s growth. About 5 million Americans have Alzheimer’s. That number is expected to grow to 16 million by 2050.

“Insufficient resources are impeding progress towards overcoming this disease,” said Peterson, who is director of the Mayo Clinic Alzheimer’s disease research center in Rochester, Minn.

Christian Baldwin of Fayetteville traveled to Washington on Wednesday in honor of his mother, Jan, who died of the disease in 2010 at age 66.

Baldwin said his mother’s decline happened over years. When things got bad and she couldn’t eat on her own, Baldwin’s father took her to an assisted-living facility. That was a financial hardship for him - he spent $4,000 a month on her care.

But even harder for Christian Baldwin was that his mother was alive, but not altogether present or responsive.

“I had to say goodbye to her before she was actually dead,” he said.

Front Section, Pages 3 on 04/25/2013