CHICAGO — Take a walk through a human brain? Fly over the surface of Mars? Computer scientists at the University of Illinois at Chicago are pushing science fiction closer to reality with a wraparound virtual world where a researcher wearing 3-D glasses can do all that and more.

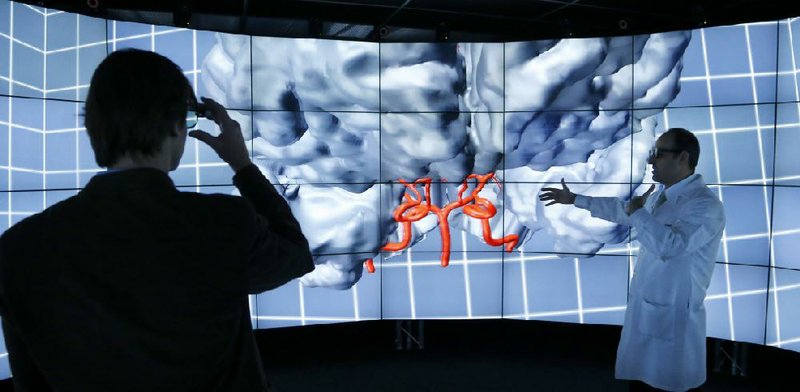

In the system, known as CAVE2, an 8-foot-tall screen wraps around the viewer 320 degrees. A panorama of images springs from 72 stereoscopic liquid crystal display panels, conveying a dizzying sense of being able to touch what’s not really there.

As far back as 1950, sci-fi author Ray Bradbury imagined a children’s nursery that could make bedtime stories disturbingly real. Star Trek fans might remember the holodeck as the virtual playground where the Enterprise crew relaxed in fantasy worlds.

But university computer scientists have more serious matters in mind when they hand visitors 3-D glasses and a controller called a wand. Today, scientists in many fields share a common challenge: how to truly understand overwhelming amounts of data.

Jason Leigh, co-inventor of the CAVE2 virtual-reality system, believes this technology answers that challenge. The original technology, introduced in the early 1990s, was called CAVE, which stood for Cave Automatic Virtual Environment.

The second generation of the device, invented by Leigh and his collaborator, Andy Johnson, has higher resolution. The project was funded by the National Science Foundation and the Department of Energy.

“It’s fantastic to come to work. Every day is like getting to live a science-fiction dream,” Leigh said. “To do science in this kind of environment is absolutely amazing.

“In the next five years, we anticipate using the CAVE to look at really large-scale data to help scientists make sense of that information. CAVEs are essentially fantastic lenses for bringing data into focus,” Leigh said.

The CAVE2 virtual world could change the way doctors are trained and improve patient care, Leigh said. Pharmaceutical researchers could use it to model the way new drugs bind to proteins in the human body. Car designers could virtually “drive” their vehicle designs.

Imagine turning huge amounts of data - the forces behind a hurricane, for example - into a simulation that a weather researcher could enlarge and explore from the inside. Architects could walk through their skyscrapers before they are built. Surgeons could rehearse a procedure using data from an individual patient.

But the size and expense of room-based virtual-reality systems may prove insurmountable barriers to widespread use, said Henry Fuchs, a computer science professor at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, who is familiar with the technology but wasn’t involved in its development.

While he calls the CAVE2 “a national treasure,” Fuchs predicts a smaller technology such as Google’s Internet-connected eyeglasses will do more to revolutionize medicine than the room-size CAVE system. Still, he says, large displays can be the best way for people to interact and collaborate.

Believers include those at Mechdyne Corp., based in Marshalltown, Iowa, which has licensed the CAVE2 technology for three years and plans to market it to hospitals, the military, and the oil and gas industry, said Kurt Hoffmeister of Mechdyne.

In Chicago, researchers and graduate students are creating virtual scenarios for testing in the CAVE2. The Mars flyover is created from real NASA data. The brain tour is based on the layout of blood vessels in a real patient.

Brain surgeon Ali Alaraj remembered the first time he viewed the brain using the CAVE2.

“You can walk between the blood vessels,” said Alaraj, a University of Illinois College of Medicine neurosurgeon. “You can look at the arteries from below. You can look at the arteries from the side. ... That was science fiction for me.”

Whether doctors can process information faster with fewer errors using CAVE2 is the question behind a proposed study that would compare CAVE2 with conventional methods of detecting brain aneurysms and determining proper treatment, said Andreas Linninger, UIC professor of bioengineering, chemical engineering and computer science.

But it’s not all serious business at the lab.

In his spare time over the past two years, research assistant Arthur Nishimoto has been programming the CAVE2 computer with the specifications for the Starship Enterprise. He now can walk around his life-size re-creation of the TV spacecraft.

Business, Pages 19 on 02/25/2013