Today, Brooks Robinson’s place in baseball lore isn’t argued.

He’s the “human vacuum cleaner,” owner of 16 Gold Glove awards, a Hall of Famer who used his 23 seasons with the Baltimore Orioles to become what many consider to be the best third baseman of all time.

Sixty years ago, though, he was a second baseman for the Little Rock Doughboys, an American Legion team that played its games on the dusty, all-dirt infield of Lamar Porter Field at the corner of 7th and Johnson Streets.

Some of his old teammates, who gathered at the field Saturday, remember him as an above-average fielder, with quick hands, a below-average arm and so slow around the bases that he earned the name “Jug Butt.”

He also wasn’t even the best third baseman on his legion team. That honor went to Harold Ellingson.

“Harold was really a better third baseman than Brooks was, if you can believe that,” said Ernie Tabor, a pitcher who later spent two years in the Philadelphia Phillies’ system.

“He didn’t even have a good arm,” Ellingson said of Robinson.

Saturday, just a few feet from the field where Tabor, Robinson and Ellingson played so many Legion games, Taylor told the story of how Ellingson was playing third base one summer and broke his shoulder in a game against Pine Bluff.

Robinson moved from second to third, and, as Tabor recalled, “the rest is history.”

Robinson doesn’t make it back to Little Rock often. He lives in Baltimore and before Saturday he hadn’t been to Lamar Porter since 2006. But he wasn’t there long Saturday before such memories began spilling out.

“I’m 76,” Robinson said Saturday. “Sometimes I can’t remember what I did this morning. But my recollection is so vivid of my youth here.”

His visit this week had a distinct purpose. Lamar Porter Field is as old as Robinson - opened in 1937 - and in need of repairs. A $4.5 million fundraiser is in order, and Robinson’s visit Saturday was accompanied by two games played by teams involved with Arkansas’ chapter of Reviving Baseball in the Inner-cities, a group run by Major League Baseball at $10 per ticket.

In between, Robinson addressed the crowd of about 1,500, and threw out two first pitches. One easily crossed the plate, another bounced a few feet in front.

“My arm is shot,” he said jokingly.

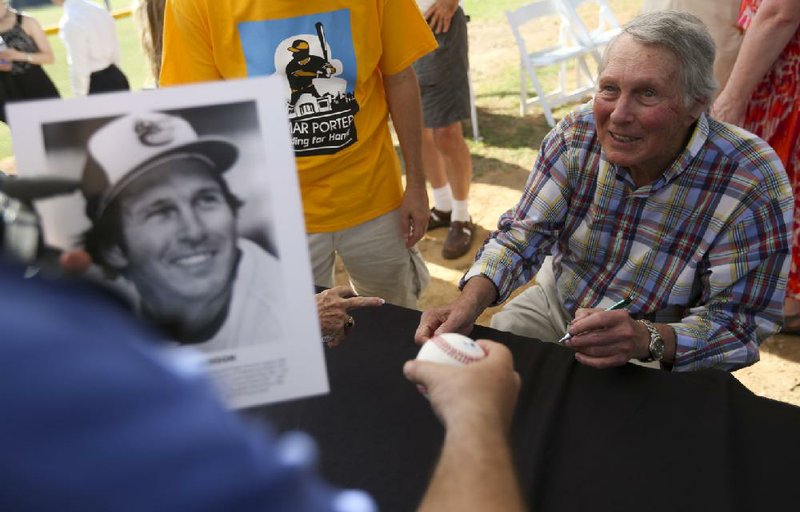

Nobody cared. A line to get his autograph began forming around 5 p.m., and by 6 had made its way through the hallways underneath the grandstand, waiting to catch a glimpse of one of Arkansas’ most treasured athletic figures.

It also served as a history lesson, of sorts, considering many of those in line, and all playing on the field, weren’t alive when Robinson retired almost 37 years ago.

Mike Townsend, 56, of Little Rock, grew up in Pine Bluff following Orioles games because of Robinson. He’s lived in Little Rock the past three decades and has had to rely on stories he remembers to tell his kids who Robinson was. His youngest son, Andrew, played in the first game Saturday, had never heard of Robinson, until recently.

Wayne Gray, commissioner of Arkansas’ RBI program, said they’ve been telling players for more than a month about No. 5.

But, growing up in 1960s Arkansas, like Townsend did, everybody knew of Robinson.

“Oh my God,” he said. “A lot of people wanted to be like Mr. Robinson.”

Robinson’s latest trip to his hometown will end today, as he heads back to Baltimore, where he’s lived since he spent the 1960s becoming one of baseball’s best and dependable players.

But Tabor, Ellingson and Weed say his legacy will remain rock solid in his hometown.

“I think Brooks’ name is engraved in this city, this ballpark,” Tabor said. “We were all surprised when he finished playing that he stayed in Baltimore. But, I mean, he could have been governor (there) if he wanted to. He’s got a good life.”

Sports, Pages 23 on 06/16/2013