GUION - Owen Rein has a grizzly white beard and he lives away from people in a clearing in a holler 10 miles from Mountain View, but he’s not some magic bumpkin making baskets and chairs ’cause he don’t know nothin’ better.

OK, philosophically, he doesn’t know any better approach to life; but also he knows a lot of other things. He’s 57 years old; he has lived in many places, beginning with his birth in Saigon to a diplomat’s family. For instance, Thailand, India, New Jersey, Kentucky, Colorado, Massachusetts, Maryland.

Also for instance, he knows that having two of his white oak baskets in the permanent collection at the Smithsonian Institution is, like, a professional bonanza.

So of course he was willing to leave his 40-acre fortress of solitude in September and haul himself 843 miles to Washington and the Smithsonian American Art Museum’s Renwick Gallery. He was more than willing to attend the triumph of his old friends Gizzard Basket (2010) and Round Bottom Basket With Lid and Handle (2010).

What traditional American craft artist working with indigenous American methods wouldn’t have been tickled to see his work ranked among the country’s best? Just because a man lives by himself in the woods doesn’t mean he’s a kook.

“A Measure of the Earth: The Cole-Ware Collection of American Baskets” was supposed to open Oct. 4. So on Sept. 18, Rein revved his 1991 Honda Accord wagon up to leafy Owen Avenue on his third-of-a-mile, grass-and gravel driveway, the way he goes once or twice a week when he’s headed to town to use the library’s computers. (His broke and he hasn’t replaced it. They don’t last.)

At the red-dirt crossroads of Turner Road West and Ridge Road, he shot straight across.

For years Rein has been trying to figure out what happens to tourists he believes do set out to find him during the Off the Beaten Path Studio Tour, an annual concurrent sale at artists’ homes around Mountain View. He thinks the brochure’s directions to his hollow could not be more accurate: “Follow Turner Road W. for a mile going STRAIGHT through the crossroads.”

But going straight apparently requires a leap of faith.

“You’re at a crossroads.You’ve got right, you’ve got left, and you’ve got straight. And I’ve even tried it holding the wheel. Like, I hold the wheel straight and see where the car goes.”

It goes directly across the intersection to Turner Road. But from the crest of the intersection, Turner appears to drop off into a rutted curve. The tourists turn.

“That’s interesting, what people will talk themselves into to avoid their fear,” he says. “‘Oh no, straight’s this way.’”

The Sept. 13-15 tour was “good,” Rein says. Of course, “I don’t get a lot of people.”

Rein’s journey east was not a beeline to Washington, but he planned it economically, with value-adding stops for woodworkers and their chairs, a lecture on his basketry method, a stroll past the remnants of the Occupy protest in New York, a visit to boyhood haunts, to favored spots for ditching school.

(“Nah, nah,” he says when asked his college major, “quit high school, quit college.”)

Every so often he’d find a computer and share poetic observations on Facebook. Like how big the sycamores have become on a certain street in New Jersey. Or the silence of a pigeon amid jackhammering urban commotion.

On schedule for the fancy gallery opening, he made his way toward the Smithsonian’s front door. Which was locked.

“It happened all of the sudden,” he says, “like a couple of days before the show was going to open, the government shut down, and I didn’t even think about it until the day before that [opening].”

He was back home in Arkansas when the show finally opened Oct. 17, but he did get to attend a consolation party in Arlington, Va. Some of the 63 artists in the exhibit gathered at the home of collectors Martha Ware and Steven Cole. “A lot of the people there, it was the same sort of thing as me - it was about kinda living in the woods in a rural area and a way to facilitate that,” Rein says. “And 30 years later, here we are.

“And it was neat, because I don’t usually get to go out and meet other people much” - not people who do what he’s been doing.

So what has he been doing on those 40 acres in Izard County, without a dog, without a mule, without a cellphone or indoor toilet, day and night, all alone, making chairs and baskets?

“I’m just following the grain,” he says, “following the grain.” But really, mostly, he’s saving money.

Straddling a draw horse - a weighty four-legged workbench/vise - he whittles a foot or so of clamped in white oak. Shrup, shrup, shrup. Long shavings peel away. Easily, the two-handled draw-knife scrapes off porous fibers, shaping first squared sides, then octagonal.

He doesn’t cut any tree until he has orders for enough furniture to use all of its trunk. Big trees are for big chairs, small trees are for baskets. A three-story white oak towers noncommittally nearby.

The most recent oak he felled, two weeks before, “was not a real big chair tree, it was probably 14 inches around,” he says, cupping the circumference in his empty hands (10 fingers intact).

He chose that tree because he had an order for four bar stools with 52-inch back legs, and he also wanted to make a tall dining room chair, because someone bought his sample, and a big rocking chair, “because I just have small ones. And so I looked for a tree that was big enough to make those four bar stools, the rocking chair and the dining room chair.”

Before he cranked his gas chain saw, he used a level and a sharp rock to scratch a guideline around the trunk. Felling a tree is dangerous. Let him scratch that cutting line. Let him take whatever precautions he can.

He chopped the downed oak into 4- or 5-foot sections. Then he took it apart.

“The tree is put together,” he explains.

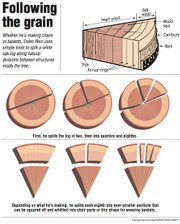

Imagine a cross-section of wood and see its annual growth rings. Radiating from the center like spokes on a wheel are xylem “rays,” lines of porous cells that carry nutrients and moisture. If you hammer a wedge into one of these rays, the log splits, dividing different types of tissue neatly.

He took a wedge and maul to the rays and split out halves, then quarters or eighths - sizes he could carry.

“I don’t need a sawmill. I don’t need a tractor. I don’t need a mule. I have a wheelbarrow,” he says.

Back at his shop, he switched to the froe, a wedge on a handle that splits out ever-smaller divisions, depending on the product - spokes, legs, shingles, whatever. Had he been making baskets (using a smaller tree), he would have gone on and on splitting, switching to a sharp knife to create long strips, each a single growth ring thick.

He split and whittled that white oak into parts for six chairs in a week and a half, but he hadn’t yet assembled the chairs: The pieces must dry slowly, braced in bending jigs in his shop.

“I work slow, but I keep all the money. I don’t wholesale,” he says, “I have virtually no material expenses. I’m all paid up. A little bit of oil, a little bit of glue. So I don’t have to make as much stuff as if I had a power shop to maintain and materials to buy and an outlet to give 40 or 50 percent to.

“And I can stay home, and I don’t have to market myself.” Customers seek him, and they pay his prices, which he deems “on the high end of normal.” For instance, his three dining room chair designs cost $250, $350 and $450.

He likes to say that he lives in the woods so he can work in the woods, and he works in the woods so he can live in the woods. Bottom line, he owns the woods.

“I already have bought and paid for all the material, all the wood that I’ll use to make my living for the rest of my life,” he says, “and I bought it a long time ago. And not only that, I don’t have to take care of it. I don’t have to keep it in the shed and make sure the bugs don’t get it. And not only that, it’s getting bigger.”

Sure, he could log his big trees and live a fat life, but then what? “People don’t make long-range plans. They make little short plans. Man, do you expect to die tomorrow? Life is long.”

He started working toward this debt-free ease amid great discomfort in 1975 and ’76, as a college dropout. When he couldn’t make $60 rent and announced a plan to live in some brush, his future father in-law instead allowed him to put a cabin on his land in the Berkshire Mountains.

With plans from Foxfire (a book on traditional folk ways) and a crosscut saw, he hammered together a 22-by-14-foot box with a sleeping loft for two young dreamers. “No running water. Kerosene lamps. But it gave us economic control,” he says.

“In the difference between material luxury and control of your economy, I would take the control of my economy. It gave us a future. From there on we could work these really crummy jobs and actually save money. In three years we saved enough money to buy land here” - in 1980 at Tomahawk Creek in Stone County.

He met Wayman Evans at the Ozark Folk Center and began learning to follow the grain in green wood.

He bought his 40 acres at Guion in 1994 when he was newly divorced. The land had been logged 15 years before, and so the trees were mostly too young for making chairs. He had to buy lumber. He suffered through craft shows and a freelance day job and had nightmares about broken rungs.

“Now I have logs all over the place. This place has what’s called a good growth index.”

Also, he has mastered the craft.

Of course it helps, a lot, not to be allergic to poison ivy.

When the recession dried up his sales in 2009, “it got down to my phone bill and my Netflix, and I really like Netflix, I really do,” he says, touching the peace sign on a chain around his neck. “And I don’t really get that many calls. I’m going, ‘Well, get rid of the phone. What the hell, I lived for years without a phone.’ But my friend said, ‘Boy, you really can’t have a business without a phone.’ And he was right.

“I kept the phone. I let the Netflix go, for a couple of months.”

He says this on a mild September morning, with crickets chirruping, red-eyed and anxious little flies buzzing too close and a lone cicada rosining its bow somewhere overhead. He mocks the flies.

“They’re all trying to move in now. Real busy. Last chance, last flowers. Yesterday morning in the sunlight they were so busy with these flowers, and you could tell they were just rushing: ‘I’ve got no time,’ ‘I’ve got no time,’ ‘I’ve got no time.’”

Poor little fools don’t know anything better.

Style, Pages 48 on 10/27/2013