You know the part in Poltergeist where a little girl bolts awake as supernatural mist curls from the blank TV screen? What about the iconic scene in Titanic where Jack and Rose “fly,” arms outstretched, at the ship’s prow? Or, one of the most expensive music videos ever made, 1999’s award-winning “What’s It Gonna Be?!,” featuring a liquid Busta Rhymes leaking from a diamond prism?

Then you know Byron Werner.

But you don’t know that you know Byron Werner, because much of his career is nebulously attributed. His name rarely flashes across the big screen. Instead, he is collectively credited at the end of a hundred or so films, many of them blockbusters from 1982 through 2004. From ’93 on, the credit often reads, “special effects by Digital Domain,” a Venice Beach, Calif., production company founded by James Cameron.

But a different household name launched Werner’s career, back in the 1970s, when he was a recent dropout from California Institute of the Arts.

He agreed to blow up a spaceship in what he terms a “ low-budget sci-fi” flick called Star Wars. Soon after, his resume included Ghostbusters, Tron and Willow, among other films.

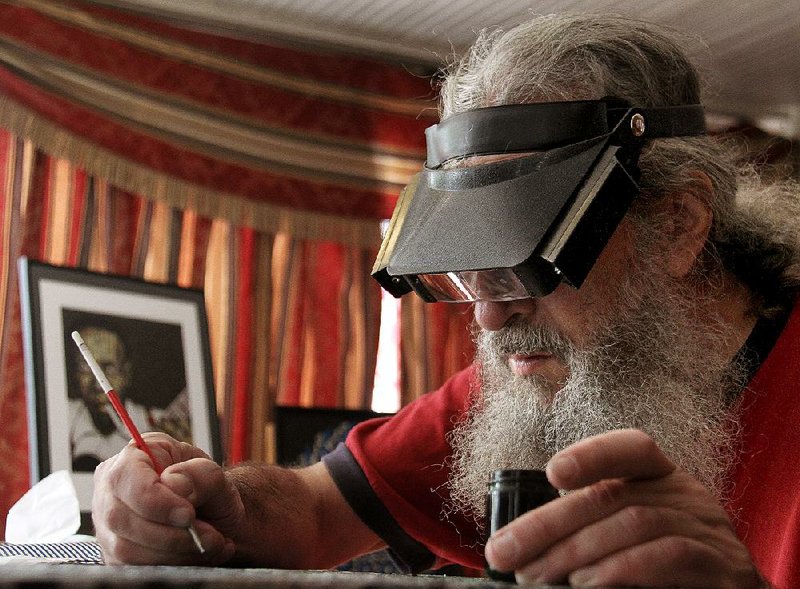

The same Byron Werner - 60, tall and bushy-bearded - can be found in the front corner of Argenta’s Starving Artist Cafe every Friday, piecing together time-intensive mosaics from wrapping paper.

Werner is also half the duo behind four hours of blips, bleeps and foreign pop broadcast on radio station KABFFM, 88.3, late Tuesday nights. His program, Rural War Room, feeds a triple-continent collective “cyber band” of the same name. Each member adds instrumentals, then passes the track along via the Internet. Werner contributes records played at hand-warped speeds, clinking bowls of water and homemade concoctions that grunt and honk.

All of this is possible because, as it turns out, Venice Beach isn’t much fun from a windowless room, and 16-hour desk-shifts tend to fuel situational alcoholism.

So in 2004, inspired by an anti-religion called The Church of the Subgenius and a shock band called Doktors for “Bob,” Werner rented a U-Haul and drove 1,600 miles east, to reconstruct his fortress of obsessions behind the facade of a Queen Anne fourplex in Little Rock’s Quapaw Quarter.

HOLLYWOOD STYLE

Werner, the eldest of six, was raised by a Time advertising rep and a Catholic housewife in an upscale Los Angeles neighborhood. He took banjo lessons, read comic books and battled a stutter.

In the early ’70s, he moved to Valencia, Calif., to attend and quickly discard art college. While there, he made connections that would carry him through a roughly 25-year special-effects career.

“He likes to call her Dummy Moore because he got so sick of looking at her,” says Donavan Suitt, Werner’s Rural War Room co-host. “He had to work on the pottery scene [of Ghost, with Demi Moore] for a really long time .… So there’s a lot of actors he can’t stand, because he had to watch their half-assed performance over and over again.”

For Werner, Hollywood was nothing but a paycheck. “I came to the conclusion that if I was going to waste my eyesight and my sanity, I wanted to do it on my own work. Plus, what I was doing with special effects, if I do my job right, you don’t see that I’ve been there at all. Which isn’t what I’m after, somehow,” he says.

OUTSIDER ART

While logging corporate hours, Werner created his own art. He began by recycling statues, concrete and plaster confections bought from thrift stores. He covered them with patterns and paisleys, tossing in the occasional “Venus de Milo with blond hair and dark roots, suntan marks and arms looking as if they were actually sliced off with tissue and bones,” he says.

Or he would stripe a third of a canvas with masking tape, paint as if the tape weren’t there, put down more tape and layer images. The result is an optical illusion, with images visible only from a distance. But he abandoned the stripes when other artists began using similar methods.

“I don’t want to copy.

I’ve got enough ideas that I can try something else,” he says.

That something else was mosaics - statues and panels dotted with shiny bits of wrapping paper, generated via hole-punches or cut freehand. The panels play off iconic photographs of musicians such as Dizzy Gillespie, Aretha Franklin, David Byrne and Jimi Hendrix, politicians such as Bill Clinton and writers such as Aldous Huxley and Isaac Asimov.

The aesthetic is often related to the subject. Werner’s H.P. Lovecraft is a straightforward portrait - brooding eyes, bony face, sensitive mouth. But step to one side and the image takes a greenish-purple tinge, overemphasizing the structure so that Lovecraft becomes skeletal and grotesque. “All of his stories are about an innocent guy, suddenly embroiled with demons or some sort of hideous thing. So I wanted this hideousness to come across,”Werner says.

He also remakes classics. He rendered Marcel Duchamp’s Nude Descending a Staircase in collaged bits of pornographic magazines and sold the piece to Leonardo DiCaprio. The original painting horrified the 1913 New York art world with its blocky, indecipherable figures, so Werner was “trying to get back to the shocking nature of it.”

There is continuity in his work. The mosaics are painterly and the paintings are mosaics, comprising short,mathematically precise brushstrokes. This is one reason Werner pushes his prints over originals.

“I do want to sell them, but I want to get what I think it’s worth. It’s not just the hours - it’s the idea, the fact that I’m doing something that nobody else is doing. It’s that my body of work will be more valuable after I die, in that I was perceived as an idea-artist and not just one piece,” he says.

Celebrity collectors (among them, Matt Groening, creator of The Simpsons, and Danny Elfman of Oingo Boingo) pay what Werner deems a fair price. Thus far, Little Rock collectors can’t or won’t. But Werner is clear on one thing: “I didn’t come to Arkansas to sell art. I came to make art.”

So he walks everywhere, subsists on oatmeal, relies on friends to pick up bar tabs and covers rent with a part-time shelving gig at the Central Arkansas Library System’s Main Library.

“I’d like to see a comprehensive book [of my work] … but I’ve kind of given up on making all my fame before I die,” he says. “Now I’m just trying to get it out of my brain into reality.”

SPACE AGE MUSIC

Werner’s infatuation with posterity extends to other artists. In 1973 he paid 3 cents for a secondhand copy of the 1958 Juan Garcia Esquivel album Other Worlds, Other Sounds.

“It had a girl and a green moonscape and streamy red stuff. I thought, ‘Wow, why aren’t people getting this just for the cover?’” he says.

At first, he only played the album at 45 or 78 rpms: “I was still making fun of it. Then I started playing it at 33 and realized that I really like this music.”

He sought out more esoteric electronica. Raymond Scott became a favorite. Werner taped albums he liked and distributed them among friends - primarily cartoonists, DJs and musicians, such as Mark Mothersbaugh of Devo. The tapes landed in influential places, and label executives dug the originals from vaults and rereleased them.

“I remember hearing Connie Chung talk about Esquivel as the comeback of the year,” Werner says.

He deemed the sound “Space Age Bachelor Pad Music,” which labels recoined as “space age pop.” (“Maybe they thought ‘Space Age Bachelor Pad’ was sexist?” Werner muses.)

Scott and Esquivel recognized Werner’s role in reviving their careers and thanked him in the liners of reissues.

POP AND PULP

In Los Angeles, Werner moved in auspicious circles. His friends weren’t renowned then, but many of them would be.

“Byron introduced me to Matt Groening when Matt was a clerk in a record store on Sunset and Life in Hell was a mini-comic he sent back to friends and family in the Northwest,” says LA-based cartoonist Carol Lay. In those days, Werner lent Groening rent money.

Lay and Werner met at the San Francisco Comic Con in 1978. “He had a briefcase with a bumper sticker that said, ‘Ask me about Famous Potatoes,’ so I said, ‘OK, what’s Famous Potatoes?” Lay remembers.

Werner opened the briefcase and handed her a self-published ’zine of bizarre, clip-art collages.

“I’d never seen anything like it. It just really pulled your mind into this back alley, to take you on a little trip where you didn’t know you wanted to go. I was immediately taken with this man,” she says. “Byron is never boring. He’s got a lot of interests … slapstick humor, trash science fiction … everything was grist for his mill.”

FORTRESS OF OBSESSIONS

All of that “grist” accumulates in the mill itself, which doubles as Werner’s current five-room apartment. Furniture burrows beneath album crates and wrapping paper. Art dots the walls. Statues line up atop bookshelves.

In another room, an old TV melts into stacked boxes and at least two dozen empty oatmeal canisters are strewn about. “I was going to use them to separate wrapping paper by color, but they just kept falling over,” he says dismissively.

Suitt explains it this way: “It’s hard to organize something that’s its own living thing … usually when artists are on the hoarder side, it’s because they’re constantly working that pile.”

Werner’s high ceilings stave off claustrophobia, and somehow he’s able to instantly find what he seeks. Right now he seeks lots of Japanese-pop: “Over there they call it ‘kawaii,’ which means weird and cutesy stuff mixed together. So they’ll have very cutesy stuff but with skulls or sharks, or a multicolored wig looking all pop and a bloody nose for no reason.”

He unfolds a multitiered CD sleeve. The male band members are decked out “ cosplay”-style, with frilly skirts, go-go boots, furry sleeves, drag-queen makeup.

There’s something Daliesque about Werner, with his hint of stutter and his upturned, wiry brows. They waggle above blue eyes, bequeathing a perpetual mischievous expression. He’s the most brilliant adolescent you’ve ever met, given to gushing. Gush-worthy topics include: the Spice Girls, Ukrainian folk music, grindhouse flicks, theremins, Moog synthesizers and the Church of the Subgenius.

SECRET SOCIETIES

Founded by two men in Dallas in 1979, the Church of the Subgenius is a club-cum-cult for irreverent weirdos. Subgenius doctrine spread through pamphlets and word of mouth. It perplexed its founders by spreading fastest of all in Arkansas. This is because Mike Keckhaver, a musician also known as Sterno, placed free ads in the then-Arkansas Democrat, soliciting Subgeniuses.

The Subgeniuses held their first national gathering in Dallas. Werner attended, and Keckhaver’s band, Doktors for “Bob” (named after “Bob” Dobbs, the organization’s fictional figurehead), played its first show. The band counted a teenage arsonist among its members and wrote all of its songs - titles include “Dump Truck Full of Dead Policemen” - on the drive to Dallas.

They “played” power tools and tossed beer cans in a blender run through an amp. One member glued hi-tops atop two guitars and strolled the stage in “guitar-shoes.” Doktors for “Bob” was the cornerstone of a Little Rockbased art-damage scene that spawned a host of offshoot bands, such as Homicidal Briefcases, the Bleeding Head of Arnold Palmer, Too Many Monas and others. Werner was fascinated.

“The thing about the Church of Subgenius, it just brought this core group together that had the same sense of humor and the same goals, to have fun and create art,” says Dotty Oliver, who was married to Keckhaver at the time and loosely documented the scene in her alt-weekly Little Rock Free Press.

In 1986, Keckhaver moved to LA for gemology school. Werner offered the couch in his efficiency apartment, and they lived together for several months. “Byron turned me on to so much good music and introduced me to so many amazing people,” Keckhaver says. “He knew all the original Zap Comix guys … he’s good friends with Robert Williams [pop-surrealist and founder of the magazine Juxtapoz].”

In 2000 or thereabouts, Keckhaver waged a campaign to move Werner to Little Rock because, “Los Angeles was killing him.” Werner was commuting from Hollywood to Venice Beach - a three-hour round trip in traffic - and trying to extract himself from a failing marriage. It took a few years, but Keckhaver succeeded.

By 2004, when Werner moved to town, the local Subgeniuses were less reactionary. There are still occasional parties, featuring events such as sawing a piano in half, but mostly, like Werner, the Subgeniuses have day jobs and radio shows. Sometimes they get together to listen to records, watch old B-films and critique local brews.

For Werner, Little Rock is cheap rent, good people, lightning storms and a change of seasons. “It’s a little town and a big town, all the stuff you don’t get in LA,” he says. “I knew I was never going to blend in. But I knew that’d be OK.”

“Edgy and Goofy” Works by Byron Werner and Amy Edgington

Saturday-Oct. 19

Gallery 360, 900 S. Rodney Parham Road, Little Rock

Opening 6-9 p.m. Saturday

Music by Rural War Room

(501) 993-0012

Style, Pages 49 on 09/01/2013