The Arkansas Board of Education voted Thursday to split the tiny Stephens School District among three neighboring school districts over the objections of the Stephens district’s leaders, who sought a merger with only one district.

RELATED ARTICLES

http://www.arkansas…">Marianna schools in state handshttp://www.arkansas…">Panel opts to review change in school site

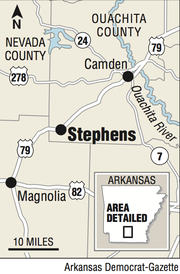

The involuntary merger combines sections of the Stephens district with the Camden-Fairview, Magnolia and Nevada school districts. The split, which will take place along county lines, was triggered when the Stephens district’s enrollment fell below the legally required minimum of 350 in two consecutive years.

“This is never an easy matter to consider,” said the state Department of Education’s general counsel, Jeremy Lasiter. “The question is not whether a consolidation will take place but how a consolidation will take place.”

The merger passed in a 5-3 vote. Board members Alice Mahony and Toyce Newton voted against the measure, and member Joe Black was absent.

The decision requires approval by a federal judge to become final because of a pre-existing school desegregation order.

The Education Board took the action on Stephens at a lengthy meeting Thursday in which it also approved the closure of Cotton Plant Elementary School in the Augusta School District.

Under the approved merger, the Stephens district will dissolve July 1, terminating all employees’ contracts with it. Current school board members in each of the three districts will serve in interim positions until rezoning is completed, and each of the three districts will have its own superintendent.

All of Stephens’ assets and liabilities will fall to the three districts following county lines, and the dissolving district’s personal property will be split among the three upon further agreement, according to the merger plan.

The data to support the tri-county merger is there, Education Commissioner Tom Kimbrell said. Stephens students would go to better-performing schools, he said, while acknowledging that all four districts are currently under “needs improvement” status.

Earlier this year, Stephens attempted to garner a voluntary partner in the Nevada district, which the majority of parents favored in a survey, Stephens’ attorney Clay Fendley said. The parties came close to reaching an agreement, but it eventually fell through, he said.

None of the surrounding school districts was interested in taking on Stephens, said attorney Whitney Moore, who represented the Camden-Fairview, Magnolia and Nevada districts. Officials didn’t see how it was feasible to continue to keep the Stephens schools open, she said.

“The general reputation of Stephens’ components is poor,” Moore said, adding that the buildings are “very old” and that while buses and other assets are in better shape, the other districts didn’t need those.

After mapping out where current Stephens students live, she said, it was “fairly obvious” to see that officials should send students who live in Ouachita County to Camden-Fairview schools, those in Columbia County to Magnolia schools and those in Nevada County to its schools.

The former McNeil School District merged with Stephens in 2004 because of low enrollment. Under that consolidation, Stephens fell under McNeil’s federal desegregation order.

Many McNeil residents opposed a merger only between Nevada and Stephens,arguing that the tri-county proposal was much easier to swallow. McNeil is some 6 miles away from Magnolia, a shorter distance than to Stephens.

McNeil Mayor Henry Warren urged the board to “look at all the figures” before making a decision.

“I don’t want our kids to be shipped to school after school down the road,” he said. “I want the decision to be permanent.”

Stephens Superintendent Patsy Hughey pleaded with the board to choose the Nevada-Stephens consolidation.

“I am definitely opposed to the split, because to me, it’s like you’re taking our students and using them like livestock and dividing them these different ways,” she said. “If the schools must close, then please let the students be together.”

Stephens is the latest district of dozens that have folded into others because of low enrollment. Under Act 60, which passed in 2004, school districts in which enrollment falls below 350 for two years in a row have to be consolidated with one or more districts. Districts can find a partner district, but if that fails, it’s up to the state Education Board to choose the hosting district.

Small communities generally don’t favor the act. Closures often lead to losing schools in small communities, which raises arguments that it hurts the towns’ identities.

“Being from south Arkansas and seeing communities decimated … sometimes it’s an oxymoron to do the right thing for the community and at the same time for the school and at the same time for the students,” board member Newton said. “Keep at the forefront the human element. Resources don’t always equate to what’s best for a community.”

Enrollment in Stephens schools for the 2010-11 school year was 355 and lowered to 333 in 2011-12. Last year, enrollment averaged 344, and there are currently 314 students in the district.

Currently, Camden-Fairview has 2,437 students, Nevada has 362 and Magnolia has 2,746.

The interim school boards will not have a representative from Stephens, and Fendley said the districts will likely vote to close the Stephens campuses. That elicits a legal question, he said, arguing that the decision to close the schools without Stephens’ representation is “taking away [their] right to vote.”

Other Arkansas communities are continuing to see the effects of Act 60 law, as well.

The Education Board on Thursday approved the closure of the pre-kindergarten through-third-grade Cotton Plant Elementary School in the 435-student Augusta district. Augusta and the former Cotton Plant School District merged in 2004 as a result of Act 60.

The state board’s vote became necessary after a divided Augusta School Board vote to close what is considered an isolated campus in its consolidated district.

Arkansas Code Annotated 6-20-602 requires any school board vote on closing a school in a former district to be unanimous. A positive but divided vote on closing a school must go to the state Education Board for a final decision.

The state board can approve the closing of a school if it is in the best interest of students and will not violate any court orders or have any negative impact on desegregation efforts.

Cotton Plant Elementary School enrolls 46 children, creating class sizes of six to 11 pupils per teacher, smaller than the class sizes in the Augusta district.

The cost of operating the school is $483,798 in salaries and utilities, Augusta Superintendent Ray Nassar said.

The savings generated by closing the campus would be reinvested into building upgrades, a new bus and technology for the remaining Augusta campuses.

The closure of the Cotton Plant school also would protect the Augusta district from being placed in the state’s fiscal-distress program, Nassar said.

It is anticipated that most, if not all, Cotton Plant staff would be able to fill vacancies at the Augusta campuses, the superintendent said.

Cotton Plant City Council member Jessie Jones objected to the closure, saying that the Cotton Plant children are among the highest-achieving in the region and that the children at the school are too small to ride a bus 28 to 33 miles one-way to Augusta.

Eirvin Lewis wrote to the state board in opposition to closing the school, saying that the community is hoping to attract a tire factory and fish refinery and the lack of a school would be a deterrent to new families seeking work there. Lewis also predicted that the displaced Cotton Plant children would more likely choose to attend the closer Brinkley School District.

Front Section, Pages 1 on 04/11/2014