He could fix you up a plate of “Beans and Cornbread,” have you partying with “Five Guys Named Moe,” tell you all about that hard-headed “Caldonia,” and let you know that “Baby, It’s Cold Outside.”

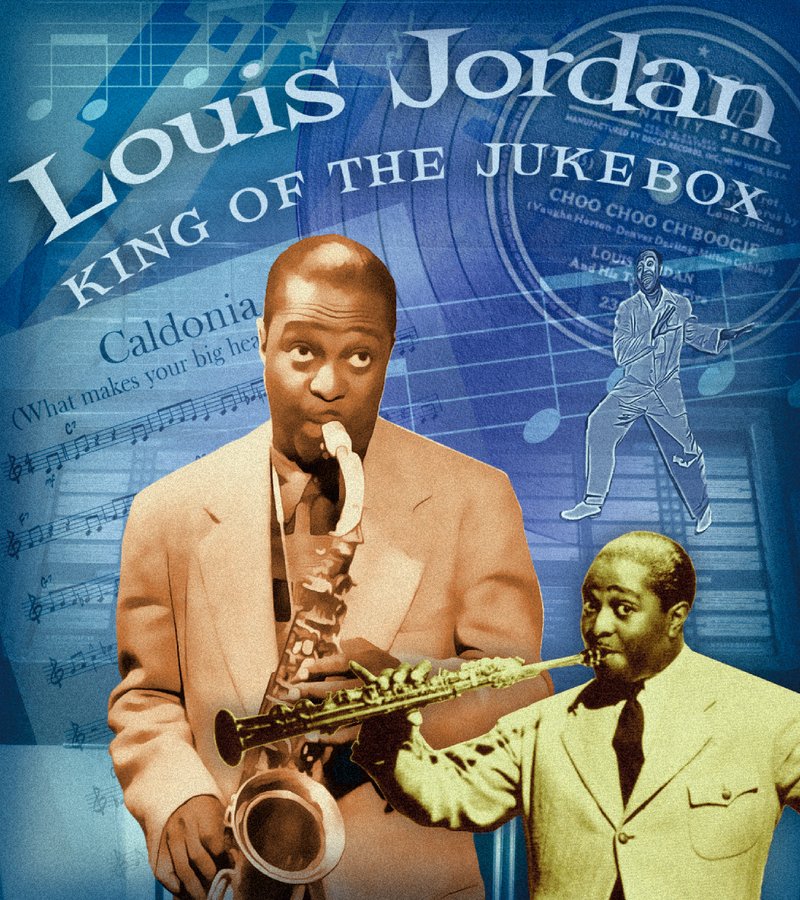

He was born and raised in Brinkley and was one of the biggest-selling musicians of the World War II era, dubbed the “Global Favorite of 11 million GIs” and he ruled as “The King of the Bobby Soxers” and “King of the Jukebox.”

His music - swinging, effervescent and delivered with undeniable joy - laid the foundation for rhythm and blues and what would later be called rock ’n’ roll; his influence was felt and acknowledged by giants such as B.B. King, Chuck Berry, Ray Charles and James Brown; and his songs have been covered by artists ranging from King to Bill Haley & His Comets, Asleep at the Wheel and Taj Mahal. He was 66 when he died of a heart attack in Los Angeles on Feb. 4, 1975.

And now he’s the subject of a new biography by Little Rock writer, radio host and musician Stephen Koch.

We are talking about, of course, Louis Jordan, so “Let the Good Times Roll.”

WHERE’S THE STATUE?

The meticulously researched book is called Louis Jordan, Son of Arkansas, Father of R&B (The History Press, $19.99) and to say that Jordan and Koch go together like, well, beans and cornbread is putting it mildly.

Growing up in Stuttgart, the son of a former disc jockey father, Koch latched onto Jordan’s music at an early age and never let go. When traveling through Brinkley as a child with his parents, Koch strained to see the statue of his hero he was sure had been erected somewhere in the town.

“Imagine my youthful horror,” he writes, “to learn that such a statue did not exist, and that most people, even in Brinkley, had never heard of Jordan.”

Koch (rhymes with “book”) has spent most of his adult life championing Jordan’s music. He organized an annual tribute concert that ran from 1997 to 2009 to raise funds for a bust of Jordan now on display at the Central Delta Depot Museum in Brinkley; wrote and performed in Jump!, a musical based on Jordan’s life; was featured in the documentary Is You Is: A Louis Jordan Story; and wrote the Jordan entry for the Encyclopedia of Arkansas. Jordan is also the muse for and a frequent subject on Koch’s syndicated radio program, Arkansongs, which shines a light on musicians with links to the Natural State, with special attention to those who may have been overlooked by the public.

“It was just always there,” Koch says about Jordan’s music in his life while sipping a beer during an interview at Vino’s in Little Rock.

After graduating with a communications degree from Arkansas State University at Jonesboro, Koch ended up in Los Angeles for a while. He paid a visit to the University of California-Los Angeles film library to track down whatever he could find on Jordan and his odyssey of spreading the gospel of the Brinkley saxophonist began.

“This guy was unknown in his home state. He had 55 Top 10 hits. He was the King of the Jukebox and influenced James Brown, Chuck Berry, Ray Charles and on down the line,” Koch says, with a barely buried twinge of frustration even after all this time.

‘CAN’T HELP BUT SMILE’

“I think it’s almost impossible to overstate the influence of Louis Jordan,” says John Miller, Arkansas Sounds music coordinator at the Butler Center for Arkansas Studies and a musician who has also covered Jordan’s songs.

“He was the first to bridge the big-band sound to the rock sound. He almost single handedly created a style of music called the ‘jump blues,’ which became rock ’n’ roll,” Miller says.

Music journalist Peter Guralnick, author of Searching for Robert Johnson, The Last Train to Memphis: The Rise of Elvis Presley, Careless Love: The Unmaking of Elvis Presley and many others, says about Jordan:

“What made his music so influential was its very accessibility. Like Louis Armstrong before him, and like great entertainers like Rufus Thomas (and Chuck Berry and Jerry Lee Lewis) in his wake, he saw it as his pure mission to engage and entertain the audience.”

That dedication to putting on a show and making music that was fun struck a chord with audiences and record buyers, especially during the 1940s.

“You just can’t help but smile when you hear Louis Jordan,” says Thomas Jacques, communications coordinator of the Delta Cultural Center and Brinkley resident who organized Choo Choo Ch’Boogie, the Brinkley music festival that started in 2003, took a year off in ’04, then ran until ’08 and paid homage to Jordan’s music.

In his book, Koch takes a straightforward and authoritative approach to Jordan’s story and music, which should come as no surprise since he worked as a reporter and was editor of the weekly alternative tabloid Little Rock Free Press and weekly newspaper The Sherwood Voice. Curiously, he refers to Jordan by the phonetic spelling of his first name, “Louie,” throughout, explaining to the reader that Jordan was often billed as “Louie” early in his career.

And what a career.

But wait, let’s talk about the beginning.

BRINKLEY BORN AND RAISED

Jordan was born into music. His father, James Jordan, was a professional musician who studied under W.C. Handy and made his living performing in minstrel shows while Louis, whose mother died when he was an infant, was raised mostly by his grandmother and, later, an aunt. All three adults in his life indulged his musical pursuits on saxophone, clarinet and trombone (though his grandmother made him practice the latter in the backyard; she couldn’t take the blaring sound) and it wasn’t long before his father recruited him to play in the Brinkley Brass Band, which toured Arkansas, Tennessee and Missouri and set Jordan on a lifelong path as a performer and bandleader.

By 1927, after touring with various shows, Jordan left Brinkley for Little Rock, playing in the city’s black clubs before realizing he could make better money in El Dorado and Smackover, where the oil boom had brought business and workers with money to spend.

“He’d long since learned to make audiences happy,” Koch writes, “but with these rough-and-tumble crowds, such a mindset was especially important, and vital to one’s health.”

There was a stint in Hot Springs, where he made contacts that got him to Philadelphia and a gig with the Charlie Gaines band, which later played with another Louis - this one played trumpet and was named Armstrong- (10 years later, Jordan and Armstrong, two of the biggest names in music, would record a duet).

In 1935, Jordan was working in Philly and New York,where he joined the influential Chick Webb Band and where he met a young singer named Ella Fitzgerald. Jordan’s first recordings in Webb’s band featured Fitzgerald on vocals, and he would later duet with her on “Stone Cold Dead in the Market (He Had it Coming),” “Petootie Pie” and others.

It was after leaving Webb’s band that Jordan came into his own as a bandleader and forged a path that would alter popular music and take it in a new direction. His Tympany Five was a new kind of band, one that wasn’t big but sounded huge. In an age where bands were 20 pieces or more, the Tympany Five was a small, tight outfit that rarely had more than seven members.

“There was the conventional wisdom that these guys couldn’t fill the big dance halls,” Koch, bespectacled with a thin, salt-and-pepper beard and a boyish enthusiasm, says. “How can this five-, six- or seven-piece band fill these big halls? Because of [Jordan’s] charisma and drive, they turned that on its head. Yes, they can fill these halls and people can come out and dance and have a great time.”

By the 1940s, with songs that were often funny and upbeat, the impeccably dressed Jordan and his equally dapper and well-rehearsed group were big time, selling millions of records, playing to sold out crowds and performing in films like Meet Miss Bobby Sox, Follow the Boys and Reete, Petite and Gone.

A QUIET DEMEANOR

Koch doggedly reports Jordan’s rise, along with a few setbacks, including marital woes - Jordan had a habit of getting married when he was married to someone else - and a vicious knifing by one angry wife. The author isn’t shy about letting the reader know that Jordan was a strict taskmaster to his band members, who came and went with regularity. And Koch points out that the singer of such good-time songs as “Choo-Choo Ch’Boogie” and “Boogie Woogie Blue Plate,” the singing, dancing, joke-telling, high-kicking entertainer was often the most reserved and taciturn guy in the room when he was offstage.

Jordan also wasn’t exactly outspoken when it came to race relations in America. Koch includes a story of Armstrong expressing his anger at the 1957 desegregation crisis at Little Rock’s Central High School. “It’s getting so bad, a colored man hasn’t got any country,” Armstrong told a reporter in North Dakota. Koch reports that Armstrong called Arkansas Gov. Orval Faubus “an uneducated plowboy” and said, “The way they are treating my people in the South, the government can go to hell.”

At around the same time, Jordan was being honored in Brinkley with a pair of homecoming concerts and remained silent on the Central High situation.

Koch quotes a 1973 Jordan interview in which the bandleader said, “Any time I played a white theater, my black following was there. [It could be] a colored theater, but white people came to see me. … Many nights, we had more white than colored, because my records were geared to the white as well as colored and they came to hear me do my records.”

Guralnick also adds that Jordan’s commercial impact as a black man selling records in Jim Crow America should not be devalued.

“At a time when the musical charts remained just as segregated as sports, housing, the armed services and every other aspect of society, he broke down barriers,” Guralnick says. “He did this in much the same way that the Ink Spots and the Golden Gate Quartet were doing it at the same time, disarming the mainstream culture with an unthreatening image that could project one thing to whites, another to his legion of black fans.”

In a strange dichotomy, the music that Jordan spawned would eventually push him out of favor. As rock ’n’ roll took hold of America’s postwar youth, the music of their parents’ generation was deemed unhip and Jordan’s star was burning out. Koch does fine work detailing Jordan’s attempts at getting back in the spotlight, which included a strange relationship with Ray Charles’ Tangerine record label, and assembling a big band, the antithesis of what made him famous.

Jordan was among the second class inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame in 1987, along with Jordan acolytes King, T-Bone Walker, Muddy Waters and Bo Diddley. In 1992, his music was featured in the musical Five Guys Named Moe and his contribution to black cinema was marked with a Louis Jordan postage stamp in 2008 (Koch bemoans that the stamp wasn’t a celebration of Jordan’s music and 100th birthday).

As for Koch’s next project, he’s pondering something - a musical, maybe? - on another Monroe County native, Sister Rosetta Tharpe.

But Louis Jordan will never be far from Koch’s mind and heart.

“I owe so much to Louis Jordan, even beyond the music,” he says. “It’s an honor just to be mentioned in the same breath as him.”

Style, Pages 53 on 04/13/2014