In January last year, Scott Ford, an owner of Little Rock based Westrock Coffee Co., and Todd Brogdon, the company’s chief executive officer, flew to Rwanda to talk with the company’s top 10 coffee growers.

“We asked them what we could do to be a better partner,” Brogdon said last month from the firm’s 56,000-squarefoot plant off Maumelle Boulevard in North Little Rock.

Westrock Coffee and an affiliate, Rwanda Trading Co., were formed in 2009 with a desire to ease the plight of Rwanda’s coffee farmers. Ford is the former chief executive officer of Alltel Corp., which was sold in 2007. Many of the people who work at Westrock are former Alltel employees.

At the end of a three-hour conversation with those 10 Rwandan farmers, what concerned them most was how they could pay school fees for their children. The fees are due in January, but the farmers don’t get paid until March when they pick the coffee cherries, Brogdon said.

Ford and Brogdon said Westrock would start a trial with just the 10 farmers.

“We told them we would make them a loan for school fees in January and the first cherries they delivered would go against that loan,” Brogdon said. “Of course, anything delivered above that, we’d pay them for.”

After the first season, the 10 farmers repaid 100 percent of their interest-free loans.Ultimately Westrock hopes to extend the program to its 50,000 farmers.

The financing program illustrates Westrock’s primary business goal.

“Our focus is the farmers and how we can help our farmers in East Africa,” said Elizabeth McLaughlin, chief marketing officer for Westrock.

Rwanda has approximately 800,000 coffee farmers. For the most part, they operate small farms, some with as few as two dozen coffee trees.

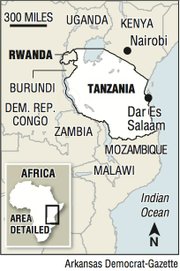

The East African country is about the size of Maryland. Rwanda has been relatively peaceful and stable in recent years after suffering a 1994 genocide, when members of the Hutu tribe killed about 1 million Tutsis and politically moderate Hutus.

With a population of about 12 million, it is the most densely populated country in Africa. It has a gross domestic product of about $7.1 billion, about 80 percent of the revenue Alltel generated in a good year. The per-capita income is $644 a year.

Brogdon, a McCrory native who started and operated a microfinancing bank in Rwanda from 2006 to 2008 before joining Westrock, declined to disclose revenue figures for Westrock. Ford said in an interview four years ago that the initial investment in Westrock was about $5 million and it lost about $1 million in its first year.

In the five years since it started, Westrock has gone from no exports to almost 5 million pounds annually of green coffee shipped out of Rwanda, Brogdon said. It is the third-largest exporter of green coffee in Rwanda and the largest exporter of higher quality, fully washed coffee, Brogdon said. The coffee is shipped to businesses in Europe, Asia and North America, he said.

About 85 percent of the green coffee Westrock exports out of Rwanda is sold to other coffee companies. Only about 15 percent goes to Westrock’s plant in Arkansas, Brogdon said.

This year, Westrock will roast about 2 million pounds of coffee, more than half of which comes from its business in Africa, Brogdon said.

Coffee producing countries - including those in Central America, Africa and Asia - are primarily impoverished, said Konrad Brits, managing director and a shareholder in Falcon Coffees in Lewes, England, south of London.

“Coffee holds this incredible opportunity for poverty alleviation,” said Brits, whose company does business with Westrock’s Rwanda Trading Co. “Because coffee is the only commodity - perhaps cocoa as well - where more than half the world’s coffee is grown by an estimated 30 million small farmers. These are very vulnerable people. So there is this latent potential.”

A few large multinational companies dominate the coffee supply chain, Brits said. Because it is the best way to manage their collateral, these companies seek to buy the coffee as close to the tree as possible, Brits said. That, however, means the farmers liquidate their crops at the lowest possible price, he said.

A number of smaller companies, including Falcon Coffees and Westrock, allow the farmers to participate in the highest value for their crop, by selling at the point of export, Brits said.

“Rwanda Trading Co. entered [the coffee business in 2009] with that same objective,” Brits said. “It’s a [gutsy] thing to do. These guys put their money where their mouth is, invested in brick and mortar and sought to upset the apple cart by trying to conduct themselves in a different way.”

Westrock’s subsidiaries - Rwanda Trading Co. and Tembo Coffee Co. in Tanzania - pay 25 percent to 30 percent above the market rate to their 90 full-time employees, as well as about 200 to 300 people who work seasonally, Brogdon said. The companies also pay higher prices for the coffee they buy than their competitors do.

In addition to improving the financial condition of the farmers in Rwanda and Tanzania, Westrock has provided clean water in the villages where it works. It has built four water stations to clean the coffee cherries but also to provide water for everyone in the village.

Before the water stations were built, villagers often would use yellow dairy cans to collect water, sometimes from a mudhole, said McLaughlin, Westrock’s marketing chief.

“It is a way we give back to the communities, beyond just the farmers, but obviously that is our connecting point,” Brogdon said.

Westrock also provides a hot meal each day, private showers and clothes for its workers, McLaughlin said. The company also teaches its farmers how to improve the quality of their coffee and improve their crop yield, McLaughlin said.

The firm’s farmers in Africa grow all qualities of coffee, and Westrock will work with all of them.

“We want to help the poorest of the poor,” McLaughlin said. “We want to sell coffee for [the high-quality and low quality grower].”

Of course, no one has found the solution to overcoming poverty, Brits said.

“Africa is littered with good intentions by failed aid and donor money,” Brits said. “I’m a very strong believer in trade and not aid. And Westrock has recognized the humanitarian need, the latent potential coffee has and done it as a commercial, for-profit business. Something can only be sustainable when it can pay for itself.”

It was difficult to talk with Westrock’s 10 top farmers last year, Brogdon said.

“It’s hard to sit across from these guys who live hand-to mouth and don’t have much money,” Brogdon said. “And here we are in our world. It’s hard to feel like you’re paying them a fair price for their coffee. Just on an emotional level - not business - it’s hard to do.

“But it’s the best thing to do. Because obviously we can’t solve the world’s problems, but we can help them, one at a time. And that’s what we’re trying to do.”

Business, Pages 73 on 04/27/2014