MINERAL SPRINGS -- After Brock Byers graduated from Mineral Springs High School in 1998, he got a tattoo by which to remember his alma mater.

A hornet, the school's mascot, is emblazoned on his right shoulder.

"It's in my blood," said Byers, 34. "I'm a real hornet now."

Yet, when the state took control of the district in May 2013 because of financial problems, he wasn't disappointed.

He felt excited that help was on the way.

By the end of the 2011-12 school year, the district was down $422,465 in unrestricted reserves, which is money available to spend in any way it chose, and it could not meet the immediate payroll for its staff, according to state Department of Education records.

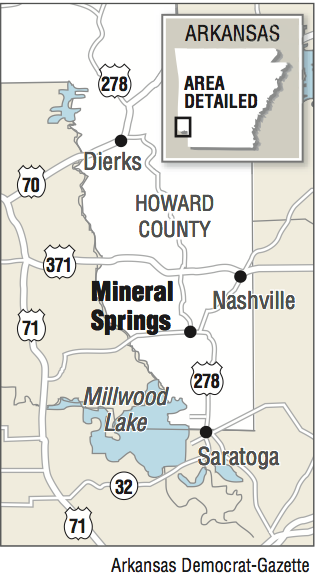

Earlier that year, the district -- which includes students from parts of Howard, Hempstead, Little River and Sevier counties -- attracted state attention when it tried to create an improvement plan for its low-performing Saratoga High. It was later revealed as a "phantom" school because all of the students listed in its enrollment actually attended the Mineral Springs campus.

In the community of 1,200 that crowds into the football stadium Friday nights for games, losing the school district hit hard, said resident Bobby Tullis, 63.

Sitting on a bench in a sparse downtown area where the city's one restaurant is located, Tullis recalled that time as horrible and full of uncertainty.

But the state-appointed superintendent helped provide more clarity, he said.

Curtis Turner, former superintendent of the Eureka Springs system, was sent to turn things around.

The Mineral Springs district has now officially closed the Saratoga campus, reduced the number of district employees by not filling open positions, restructured its bond debt and enacted a new protocol for buying equipment, as well as other financial controls.

The reorganizing of local tax structures to include revenue from a nearby coal-fired power plant also helped, Turner said.

Revenue from the John W. Turk Jr. Power Plant in Fulton formerly went to the Hope School District, but the property was recently discovered to be split between the Mineral Springs district and the Hope district.

Now, both school districts receive a cut of the money.

For 2013 taxes payable in 2014, the Mineral Springs system got $5,475,575 from Hempstead County, the bulk of which was from the power plant, Turner said.

"That was a savior for our district," he said. "It took quite a bit of work, but we finally did it, and now we've got the money diverted back to us."

That money will fund improvements to the district's facilities and staff, Turner said.

For the recently started school year, Turner has hired a new principal and two new teachers for the elementary school, along with an additional curriculum coordinator for the district.

After the state took control of the district in 2013, it dissolved the School Board. But a new School Board is on tap in the near future.

In all, there are seven seats available. Three candidates are running as contested, and four are uncontested in the School Board election on Sept. 16.

Mike Erwin, who was on the School Board that was dissolved, is among two other previous board members running unopposed.

Erwin, who had two grandfathers serve on the School Board, said the new board's role will be to set policy, which includes approving contracts and holding staff members accountable.

"I think we need to make sure that we have a functional board that understands their role," Erwin said. "With my experience, I think I can give an example of that."

Having a School Board with experienced members will help with the transition back to local control, said Bald Knob Superintendent Bradley Roberts.

"They want to make sure they are doing what's correct legally, and they don't want to wind up in fiscal distress again," he said. "You need seasoned board members who are able to say, 'We can do this,' or, 'We can't do this,' even though they all go through extensive training before their term."

The Bald Knob district in White County was placed under state control in September 2007 for financial distress and worked its way back to being locally run by January 2009.

Roberts, who graduated from the Bald Knob system, was not superintendent then. But he remembers the morale in the town where he grew up.

"The first 24 hours were extremely difficult," he said. "The wind had just been pulled out of the whole community."

Declining enrollment was another challenge the Bald Knob district faced in the wake of the state takeover, Roberts said.

The district had already been on a downward spiral for a couple of years, and the state takeover exacerbated that. Some parents may have pulled their kids out of the district and put them in private schools or sent them to other areas.

According to state law, if the student body drops below 350 for two consecutive years, a district can be annexed by or consolidated into neighboring ones.

Turner said he expects Mineral Springs to face challenges over that figure.

The district's enrollment totals 420, and Turner estimated that about 60 students left during the state takeover.

"The biggest challenge that I see for the district is its numbers of students," he said. "I can fix and do a lot of things on my end as far as taking care of the school's finances, but the one thing that I cannot control is the number of students we have."

Knowing that obstacles lie ahead, Byers said he is still hopeful about the future for the Mineral Springs School District.

As he worked behind the counter at his family-owned gas station cafe -- B's Quick Stop & Grill -- ringing up customers, Byers thought about his time playing football in high school. Ultimately, his education at Mineral Springs helped him pursue a degree in criminal justice in college.

"It can only go up from here," he said. "We can't go down to where we've been."

State Desk on 08/25/2014