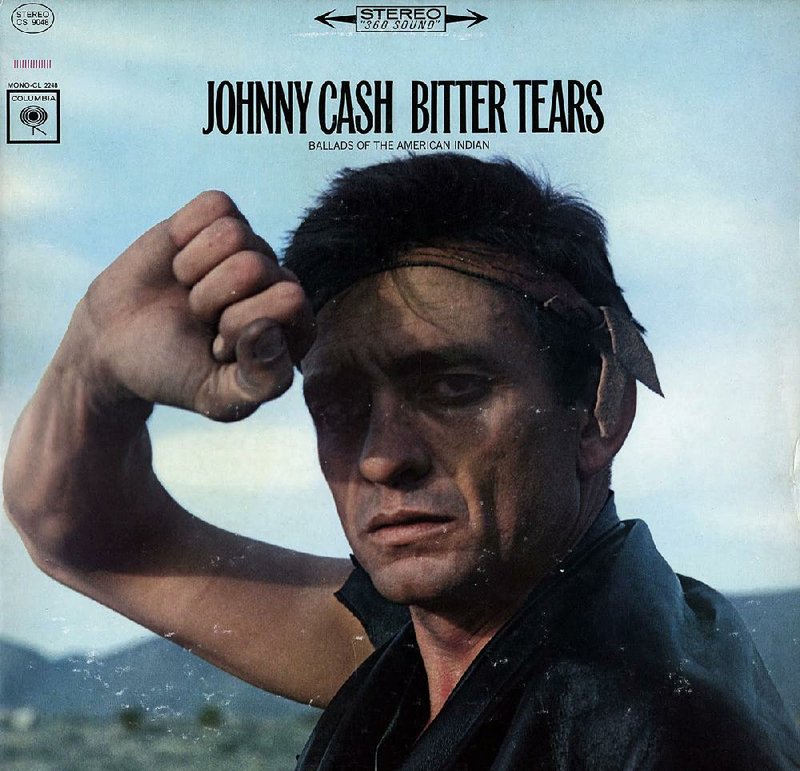

"Cash, in narrative and song, documents the tragic history of the American Indian."

-- Billboard entire review of Johnny Cash's 1964 album Bitter Tears, from the Aug. 22, 1964, issue.

"Where are your guts?"

-- Johnny Cash, in a full-page ad that challenged radio "D.J.s -- station managers -- owners, etc." to play the album in that same issue of Billboard.

My paternal grandmother lived with us when I was a small child. She sewed all my clothes and played cowboys and Indians with my sister and me during the day while my parents worked. To us she wasn't Granny or Grandma or Nana. We called her Sheriff, and the mental image I keep of her in my mind's gallery is of a photograph I once saw of her smoking, with a child's red felt cowboy hat on her head and a plastic chrome-plated six-shooter in her hand.

When I was about 5 years old, she told me she was half Cherokee. While I don't remember the context, her statement always stuck with me. I had no reason to doubt her then, and later it made sense to me. She looked a little like the stereotypical American Indian, with high, sharp cheekbones and a relatively dark complexion. She was from Tennessee. She might have been exaggerating the amount of Indian blood she had, but I took it for granted that my blue-eyed father could be, if not one-fourth Indian, perhaps one-eighth. So I could be one-sixteenth, or maybe one-sixty-fourth Indian. I hold on to that belief to this day. (I hope for a few expiating drops of blood. #NOTALLWHITEMEN.)

Of course, adults tell children things that aren't true all the time. When I think back 50 years, I understand it is more than possible that Sheriff was teasing me. Indians were big when I was a kid. We made headdresses in school, we watched white actors in pancake makeup and buckskin play them on TV and in the movies. They were necessary to backyard games. At the time of her revelation, we were even living in a subdivision in semi-rural North Carolina called Ogalalla Village ("Ogalalla" being a misspelling -- or at least a different spelling -- of "Oglala," the name of a High Plains Lakota tribe that never ventured anywhere near North Carolina).

It was about that time my parents brought home a new Johnny Cash record. It was called Bitter Tears: Ballads of the American Indian, and I was struck by the cover photo, which showed a gaunt (and, according to his longtime bass player Marshall Grant, pilled-up) Cash in a tight leather headband and what looked to be a leather vest, his right arm crooked oddly and his hand dramatically shielding his eyes from what I supposed was a blazing desert sun.

My parents were probably typical music consumers of the time. In their late 20s they were a little old for Beatlemania; their record collection was small and eclectic. Along with Ray Charles and Fats Domino, they had Patsy Cline, Elvis Presley and Jack Green records and Cash's Blood, Sweat and Tears album from 1963. My father probably liked Johnny Horton's history songs better than Cash's dark growl. The record I remember being played most often when I was a child was Horton's greatest hits. "North to Alaska," "Sink the Bismarck" and "Comanche the Brave Horse" are all imprinted deep in my memory (as was Horton's version of Jimmy Driftwood's earwormy "Battle of New Orleans").

But I don't remember them playing Bitter Tears much. While I do remember my father explaining the story behind "The Ballad of Ira Hayes" to me -- he told me Hayes was a Pima Indian war hero who was one of the men in the iconic Iwo Jima flag-raising photo. After the war, he returned home and died when he got drunk and drowned in 2 inches of water in a drainage ditch. I don't know whether I heard the song on the radio or my parent's Magnavox. Probably on the radio.

STRONG MEDICINE

Bitter Tears was a fierce and, in retrospect, remarkably important album. Cash had already begun to embrace the politics of folk music with Blood, Sweat and Tears, a collection of songs about the American proletariat, but Bitter Tears fit in with protest songs that singers like Bob Dylan (who'd soon abandon them for Rimbaudian surrealism) and Joan Baez (who wouldn't) were recording. The album was, as Cash would write in an open letter to the nation's disc jockeys (who, by and large, ignored the album's release) "strong medicine ... So is Rochester, Harlem, Birmingham and Vietnam."

Cash, driven in part by his (perhaps dubious) belief in his Indian heritage, was deeply invested in the project, although his record company, Columbia, was reluctant to promote it. (Even so, "Ira Hayes" rose as high as No. 3 on the Billboard Country Singles chart in the summer of '64.) He used a good deal of his capital as the top country artist in the country -- he was just coming off the No. 1 success of the single "Understand Your Man" and the No. 1 album I Walk the Line -- to get the album made. To do so he enlisted the help of Peter La Farge, a folk singer who wrote "Ira Hayes" and four other songs on Bitter Tears.

"Peter was a genuine intellectual, but he was also very earthy, very proud of his Hopi heritage, and very aware of the wrongs done to his people and other Native Americans," Cash wrote in his 1997 autobiography. "The history he knew so well wasn't known at all by most white Americans in the early 1960s ... his was a voice crying in the wilderness."

But, the thing is, La Farge's Indian heritage is more tenuous than Cash's -- or for that matter, my own. He was born Oliver Albee La Farge, the son of Oliver La Farge, a Pulitzer Prize-winning novelist and anthropologist, and Wanden Matthews La Farge, a Rhode Island heiress. While Oliver La Farge was one of the country's foremost experts on Indian culture (his Pulitzer winner, Laughing Boy, is a coming-of-age story of a Navajo youth), a leading advocate for Indian rights and president of the Association on American Indian Affairs -- his family came over on the Mayflower. Peter sometimes claimed that he was adopted and/or descended from the Narragansett Indian tribe, but it seems highly unlikely he was an authentic Indian.

(La Farge died in 1965, and like the rest of his life, his end is occluded by rumor, wishfulness and deflection.)

BETTER IN THEORY

To be fair, Cash's Bitter Tears plays better as an important historical artifact and evidence of Cash's courage and social engagement than as a work of art. "Ira Hayes" is by far the best track on the record, although La Farge's "Custer" is a mean, gleeful gloat, and the Johnny Horton-penned "The Vanishing Race" benefits from a terrific vocal performance. Cash's songwriting isn't up to his highest standards. The album's nadir is "The Talking Leaves," a recitation that tells the story of Sequoyah, the inventor of the Cherokee alphabet, in the tritest and most maudlin way possible.

Similarly, the best way to receive the recently released tribute Look Again to the Wind: Johnny Cash's Bitter Tears Revisited, recorded by a group of country and Americana stars and produced by Joe Henry, is a kind of castigation. America seems no closer to coming to terms with the "tragic history of the American Indian" 50 years after the release of Cash's album.

Once again, "Ira Hayes," performed here by a fiercely rumbling Kris Kristofferson, is the best cut, with Steve Earle's version of "Custer" pushing it hard. Bill Miller, a genuine American Indian artist who has won three Grammy awards, performs the title track, a La Farge composition that didn't appear on the original album. Other contributors include Emmylou Harris, Gillian Welch and David Rawlings, Carolina Chocolate Drops singer Rhiannon Giddens and the Milk Carton Kids.

As much as I wanted to like the album -- and I do like much of it, especially the close harmony of Welch and Rawlings -- it has the curated, respectful feel of a eulogy for a beloved statesman rather than the furious broadside Cash intended. It's too pretty, too wistful.

Johnny Cash's claims to Mohawk and Cherokee heritage probably weren't legitimate. Peter La Farge was likely as WASPy as one could be. Iron Eyes Cody and Forrest Carter weren't real Indians. Maybe my Sheriff didn't have any Indian blood either.

But Cash's empathy was genuine; the risks he took were real ... as real as the injustices he addressed.

Email:

pmartin@arkansasonline.com

Style on 08/31/2014