’Tis the season for that annual KUAR-FM, 89.1 public radio kibitz klatch, the Two Jewish Guys Chanukah Special, that “Little Rock Christmas tradition.” Where is it?

For the first time in 13 years, Philip Kaplan and Leslie Singer missed the Festival of Lights/Yuletide broadcast. So, maybe “tradition” is a bit put-on.

“I’m glad we stopped, actually,” says Singer, who did not exactly wish to stop. “Face it, Phil’s got bigger fish. You know, I’m in marketing. I’m a clown. This is it for me. Phil is, you know, a tall-building lawyer, and he’s got serious stuff going on.”

The Two Jewish Guys began fortuitously enough when Singer and Kaplan met over microphones inside the KUAR studios in the 1990s. It was a pledge drive, but instead of schnorrers the listening audience of roughly 32,500 heard two Jews riffing on Hebrew school, their mothers, Yiddish and their favorite pickled fishes and it was a hit. Well, a public radio hit.

In 2001 the station gave the men a one-hour spot. It was, simply, the Chanukah Special.

“I’m pretty sure that they contemplated that it would be seriously ethnic,” Kaplan remembers, “and indeed we tried to make it seriously ethnic, and from the very beginning, even fundraising, people were always highly complimentary. … We have groupies, you know. We do! They’re of a certain age.”

Imagine you go to Harvard College and the University of Michigan and, still a young lawyer, you’re fighting the state’s penitentiary system because inmates have complained about something called the Tucker Telephone, and imagine the case goes to the U.S. Supreme Court and the only dissenter is William Rehnquist. Imagine you take on school desegregation and make a First Amendment argument for the right to stage Hair at Robinson Auditorium. Imagine for this body of legal work you’re one of roughly 200 living Arkansans who has his own entry in the Encyclopedia of Arkansas, and, after all that, people say, “Hey, you’re one of the Two Jewish Guys!”

“He’s a mensch,” Singer says. “He’s like a real mensch, a man of honor, and you’re right, that’s probably what’s going to happen to him.”

“I did run into a lawyer trying a case a couple years ago [who] travels around the country. When he tells people he’s from Little Rock he gets asked if he knows the Two Jewish Guys,” Kaplan says. “I don’t know if he’s pulling my leg.”

MLK COMMISSION

In 2009 the Legislature and governor enacted Act 309, which placed the governor in charge of hiring or firing the executive director of the Martin Luther King, Jr. Commission. The year before, Gov. Mike Beebe called the discord in the commission “an embarrassment to Arkansas.”

Beebe appointed five new members to the commission including a chairman, Kaplan.

“Irritated is not strong enough a word for how disappointed and upset I was at the infighting going on over there,” Beebe recalls. “If there was one human being who had both the temperament, and the heart — and the ability, the sheer willpower and leadership ability — to put it back on the track, Philip Kaplan was on the top of the list. And, you know, I got some criticism from African-Americans for appointing a white guy as chair of the commission, but the commission, and Dr. King would be the first to tell you, this isn’t about racial segregation, it’s about inclusiveness, and he has done a marvelous job.”

Created in 1993 to promote the legacy and philosophy of King — namely, harmony and civic involvement — the commission will host an interfaith prayer breakfast in Little Rock on Jan. 19 at which many local and state politicians are expected. At 10 a.m., the “party” moves to the Benton Event Center where the guest is actor Eric Braeden (Victor Newman from The Young and the Restless) and folks are expected to fan out and offer service to their communities (reading to the infirm, coat drives and other decentralized good deeds).

Before commission Director DuShun Scarbrough, who came on in 2008, and Kaplan, the big holiday event was a gala. Scarborough and Kaplan helped steer it toward service in communities around the state. “This is not just an agency that’s welcoming African-Americans. Dr. King welcomed all.”

Scarborough called Kaplan a “civil rights pioneer” whom not enough Arkansans know about because “Phil’s the type of person who, when he’s done something [noteworthy], he doesn’t really, I don’t know what you call it, he doesn’t want to be recognized.

“I don’t know what kind of person you’d call that.”

Though not a socialite and, therefore, not a regular in these pages, Kaplan volunteers frequently, often “indoors.” Along with the King Commission, he’s on the editorial board for The Arkansas Lawyer (six years its chairman). “It’s very unusual for someone to chair that committee for that long. It’s a lot of work,” says editor Anna Hubbard.

Rabbi Eugene Levy points out that Kaplan has been on boards and committees for Temple B’Nai Israel, Congregation Agudath Achim and the Jewish Federation of Arkansas. “He sat on the search committee that brought me here in 1987.”

He’s a past board member of KUAR/KLRE-FM (public radio) and a current board member of the Arkansas Symphony Orchestra and the AETN Foundation, which supports the Arkansas PBS affiliate: “Can you imagine there are people in our Congress who want to do away with PBS?” he says. “It’s staggering to me that you can be that anti-intellectual.”

During this interview fellow Williams and Anderson law partner Harold Evans knocked on his door to say, “I was instructed to ask if you’d be part of the Christmas program at Rotary.”

“What?” Kaplan asked plaintiffly. “I’m not a Rotarian. I’m not a joiner of organizations.”

“Well, that’s not a requirement for Rotary.”

Later, Evans said “He may not be a joiner of organizations but he is a strong supporter when asked.” He has volunteered to interview Harvard University applicants for years, and that intercession probably made the difference in some of those admissions, Evans said.

THE FILE ON KAPLAN

“Listen, I get this call after [Chief] Gale Weeks had left the Little Rock Police Department,” Kaplan says. “I get this call from Sonny Simpson — [Simpson was] not a favorite son within the department, but when the broom swept through he was made the chief.”

“He said, ‘Phil, if you want to come down and see your secret file before I destroy it, you’re welcome to do so.’ [Weeks] kept files on people just the way Hoover kept files on people.

“So I went down to look at my secret file, and who’s in my secret file [but] Sweet Sweet Connie. You know Sweet Connie? I have no idea why or how [these couple of articles on her] got in there. I don’t know the woman, didn’t know the woman, have no idea … but there it was — and that shows you the level of intelligence of the folks who are gathering the information.”

The newspaper’s own file on Kaplan begins in 1969 and consists of nine separate envelopes: a lot of clippings as these things go. It ends at the close of the 1980s when news was uploaded to a server and the paper file library became what it was always called by reporters, a “morgue.”

The very first clipping simply says the state’s only integrated law firm at the time, (John) Walker and (Burl) Rotenberry of Little Rock, added Kaplan, who had most recently represented a group of white students attempting to intervene as plaintiffs in the city’s school desegregation case. When it failed, he joined Walker and Rotenberry representing “Negro plaintiffs.”

Kaplan had concerned himself with labor unions, students and civil liberties when later that year U.S. District Court Judge J. Smith Henley called Jack Holt and Kaplan to his office. There was a pile of writs filed by inmates at Cummins and Tucker prisons alleging mistreatment and torture. Eventually, all of the writs were consolidated, and the case Holt v. Sarver was litigated. (Holt is not Jack Holt but the surname of an incarcerated complainant; Robert Sarver was the state commissioner of corrections.)

Once, Kaplan and Holt flew down in Holt’s own plane in January to meet with Sarver at the Cummins prison farm. When they arrived, the commissioner wasn’t there to greet them. He’d gone into town to buy propane to heat the guard towers, which were manned by trusties with rifles. Sarver bought the heating fuel with his own money — “well, that was our first familiarity” with the deficits of the state’s prison system, Kaplan said.

Henley eventually ruled against the state’s entire corrections system.

When Dale Bumpers became governor he overhauled the top brass and brought in a number of prison administrators from Texas, but by 1974 inmates again challenged their treatment, and in a subsequent case — Finney v. Hutto — the Eighth Circuit Court of Appeals ordered relief and court jurisdiction over the prisons. In 1978, the U.S. Supreme Court addressed a couple of decisions made in the many lower court decisions stemming from Finney v. Hutto, including solitary confinement (it must be limited to 30 days), and the matter of attorneys’ compensation in civil rights/civil liberties cases (a fee is reasonable).

“We litigated something called Texas TV,” Kaplan says, getting up and leaning his forehead flat against the wall, several inches beyond his toes. “They were forced to do this for hours. You’re not put in prisons to be, I mean, you certainly are to be punished, but not to be tortured!”

JEWISH, NOT JEWISH

One of Singer and Kaplan’s best loved riffs is “Jewish, Not Jewish.” We all know menorahs, preserved fish and becoming verklempt are Jewish, but what about key strokes, housewares or technology? Singer and Kaplan can tell you. Corduroy, for example, is Jewish, but rayon? Not Jewish. Allergies is certainly a Jewish malady. Tennis elbow? Not Jewish. Of the periodic table, hydrogen, sulphur, and lithium are Jewish. Ununpentium, certainly not. Cadillac is Jewish. Pontiac? No.

Over the course of several Chanukah Specials a listener gets the sense that Kaplan is very Jewish.

“I always say, Phil’s the Jew. I’m sort of Jew-ish,” Singer says.

The primogeniture of a couple of Ashkenazi immigrants, Kaplan grew up outside of Boston. His dad was a kosher butcher and merchant; his mother cooked and prepared the food. In fourth grade he heard “Philip” during roll call and didn’t raise his hand — his mother had always called him “Eddie.” She didn’t think Philip was an appropriate name for a little boy though, in fact, she’d named him.

He has about as many memories of Hebrew school as of the secular ones. At Harvard he experienced very little anti-Semitism because, at the time, the campus was about one-third Jewish.

With a juris doctor from the University of Michigan, he got a job with the National Labor Relations Board in St. Louis where he crossed paths with a United Auto Workers attorney in Little Rock, Jim Youngdahl. It was Youngdahl who entreated Kaplan to join McMath, Leatherman, Woods and Youngdahl.

“I think Jews of my generation, so close to the immigrant generation, had social justice as something that motivated them,” Kaplan says from his office on the 22nd floor of the Stephens Building. “Jews say a responsibility to ‘repair the world,’ tikkun olam, is something that you live by. It’s in the DNA.”

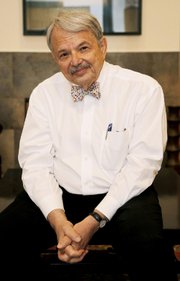

Does Philip Kaplan have a fourth act in him, an encore? That’s the question before this 76-year-old, and when he entertains it, his eyes twinkle, and his thick lips spread across his bright teeth, but what he says is, “I doubt it. I don’t think so.”

It’s a bittersweet reflection, to know you’re finishing up, even if you’ve accomplished so much.

Tuesday, Singer and Kaplan brought the Two Jewish Guys back for an abridged, unrecorded performance for Rotary Club 99 at the Clinton Presidential Center, where for the last seven years they had performed and aired their Chanukah Special. Just before lighting the menorah, Kaplan marveled — in all these years, “we’ve never actually done [the show] on Hanukkah. It’s the first time, and for that, we are so grateful to Rotary.”

“I don’t think it’s such a big deal,” Singer groaned.

Afterward, asked if he could spare some time for a phone call in the afternoon, Kaplan feigned hurriedness before confessing he has very little if anything on his agenda.

“Ruthe’s wanted me to be fully retired for a long time, I just can’t bring myself to do it. One, I still love what I do. Just the practice of law. I still love to go to the office every day, and I love to be around other lawyers every day.”

His longtime law partner (until recently) JoAnn Maxey said Kaplan’s biggest weakness as a lawyer was probably the business of running a law firm, the commerce of it — never the case load, never the personnel.

“In fact, when we got to Williams and Anderson, they would tell you, with regard to personnel issues, he’s a great person to have at a larger firm because he’s such a fair person and looks out for the interests of everybody. He just knows how to resolve situations.”