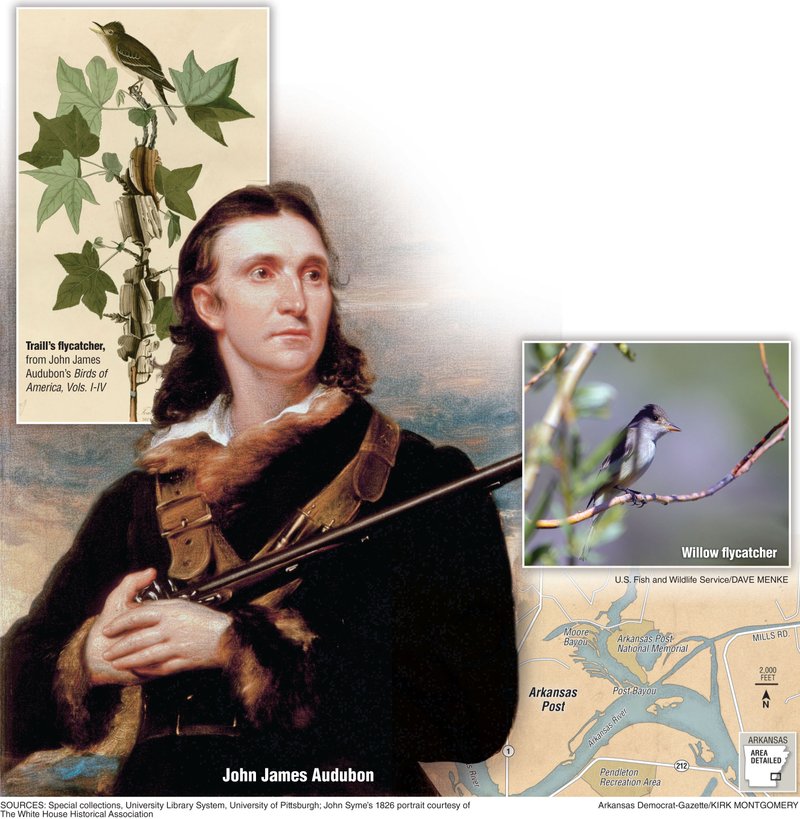

The first documented case of bird-watching tourism in the state of Arkansas may well have been the greatest. It happened in the 1820s, when John James Audubon paid two visits to Arkansas Post.

The 35-year-old painter and ornithologist, stinging from the bankruptcy of his steam-driven mill business in Henderson, Ky., took a steamboat down the Ohio and Mississippi rivers. He planned to draw every species of bird in America and then to publish his drawings in a book that could support his family. As it turned out, his book -- The Birds of America -- also would make his mark upon history.

On Dec. 22, 1820, Audubon reached Arkansas Post, a frontier village near the convergence of the White, Arkansas and Mississippi rivers. He spent Christmas week there. In April 1822, he returned. The first trip is better documented than the second. His journals do not always mention specific dates with each event, and it is necessary in some instances to make inferences from his observations to build a sensible narrative. But we know that on both trips he hunted, killed birds and drew.

Audubon (1785--1851) hunted using shotguns filled with tiny "mustard seed" shot. Some birds he killed for sport, but many he killed for food. He slayed hundreds of birds and preserved their skins with arsenic to sell as specimens to museums and private collectors. He sacrificed others so he could pose them by impaling their carcasses with pins or wires on a board so they would serve him as models for his drawings.

Audubon's "life list" was essentially a "dead list": birds he had killed and painted for inclusion in his monumental work, The Birds of America. This elephant-size book contains life-size paintings of more than 400 birds. Most of the color plates are images of birds in their natural settings with typical plants, prey and postures. He didn't use oils to paint the birds but rather mixed media he developed using pencil, chalk and watercolors.

Only occasionally did he draw from memory or by looking at a live bird, but he spent hours and days observing birds in the wild and learning their habits.

Sometimes, instead of shooting wild birds, he attempted to domesticate fledglings or injured birds and keep them around his home as pets and models. He tried this with turkeys, quail, parakeets and wood ducks.

There is scant evidence that he was as much concerned with the conservation of birds as is the society that today bears his name. Late in his life, he was alarmed by the decline in bird populations, but he did not restrain himself from contributing to that decline.

For example, while in Labrador, he complained in his journal about egg collectors who took thousands of eggs from the nests of sea birds to sell to New York markets. He predicted, correctly, that such egg collections could result in these birds becoming extinct. But in the same journal entry, he reported asking his companions to kill, skin and preserve 300 birds to sell to collectors in England.

OUTPOST

Arkansas Post was a political, military and commercial center for centuries. The Encyclopedia of Arkansas History and Culture

credits its founding as a French outpost, in 1686, to Henri de Tonti, an officer given land as a reward for serving on a 1682 Mississippi River expedition led by Rene-Robert Cavelier, Sieur de La Salle. It was a trading center for Quapaw, Chickasaw, Osage and Caddo Indians. The area was alternately claimed by France and Spain until sold to the United States in 1803 as part of the Louisiana Purchase.

When Audubon first visited, the village was the territorial capital of Arkansas. It had a trading post, a cotton gin, a tavern, a dry goods store, an inn (where the painter stayed) and a fledgling newspaper, the Arkansas Gazette (first published in 1819). According to Audubon's journal, a Mrs. Montgomery, the tavern keeper's wife, "was a handsome woman with good Manners and rather superior to those of her rank in Life." Audubon does not mention Mr. Montgomery.

That first edition of the Gazette bore an advertisement for Lewis and Thomas' Trading Post and among items listed for sale were "six cases of ladies hats with feathers." Within about 70 years, overhunting of birds to collect feathers for ladies' hats would raise the alarm for protecting birds and give rise to the conservation movement in America, including the first Audubon societies.

Audubon did not report every bird he saw at each stop on his journeys, but in and around Arkansas Post he did report seeing at least 17 species.

On the day before he landed at Arkansas Post, apparently while still steaming down the Mississippi River, he finished a painting of a black vulture that now hangs in the Museum of the New York Historical Society. He reported no vultures at the post, however, though surely they were there.

In one sentence he mentioned seeing "cardinals, the Iowa Buntings [possibly eastern towhee], the Meadow Larks and Many Species of Sparrows." He repeated what he thought was a credible report of a "large white hawk with a perfectly red tail" that had been killed there just before his arrival; but the identity of the bird is lost to history.

He killed four remarkably tame crows to make writing quills of their feathers. He saw two hawks, most likely red-tails, "a great number of Geese and Mallards and Some Blue Cranes" that might have been great blue herons.

He also reported seeing two flocks of a bird that was unfamiliar to him that he initially thought was an albatross, but at Arkansas Post he referred to them as "these unknown divers or pelicans." From his descriptions, they were almost assuredly double-crested cormorants -- "water turkeys."

He also mentioned seeing nesting bald eagles and wild turkeys.

LOST SPECIES

He spotted two birds that today are usually considered extinct, the Carolina parakeet and the ivory-billed woodpecker. Audubon noted that some people in the area thought the flesh and organs of the parakeet were poisonous. He dismissed that notion since he had eaten them himself, but he did agree that they weren't very tasty.

Along the Arkansas River, he observed that the number of ivory-billed woodpeckers "has grown more plenty." Audubon tells the story of one of his hunting companions, a man named Aumack, who shot and wounded an ivory-billed woodpecker only to see the bird flutter to a nearby tree and scramble up the trunk.

Aumack shot the bird again, knocking it to the ground. When Audubon went to the base of the tree to pick it up, with its dying gasp, the crow-size bird pecked his hand, producing a deep wound that did not heal for several weeks.

FLYCATCHER

When he returned 16 months later, the territorial capital had moved up the Arkansas River to Little Rock.

During this April 17, 1822, visit, Audubon shot and painted a species he had never seen before. He skinned the small female bird, which had "five pea sized eggs" developing inside. He treated the specimen with arsenic to preserve it and, eventually, delivered it to The American Museum of Natural History in New York.

Audubon subsequently named it Traill's flycatcher in honor of an English naturalist, Dr. Thomas S. Traill, who had helped Audubon begin his publishing and lecturing career.

At other times Audubon called it the "Arkansas flycatcher." It is considered the only species of bird discovered and scientifically described in the Natural State.

More than 150 years after Audubon painted this small insect-eater, the American Ornithological Union concluded his Traill's flycatcher should be categorized as a member of either the "alder" or "willow" flycatchers. Neither Audubon nor Traill's name remain associated with either bird. Doug James, a biologist of the University of Arkansas, writing in the Journal of the Arkansas Academy of Science in 2003, persuasively argues that the bird Audubon shot was a willow flycatcher.

The willow flycatcher is a difficult bird to distinguish from its cousins in the Empidonax family. Four of the birds in this family are impossible to distinguish from one another by sight alone. One must recognize differences in their songs. It requires a keen ear to do that, and during some seasons the birds don't sing.

BAMBOO

While Audubon was at the Post he took a boat trip with Osage Indians into some of the bayous nearby hunting for birds, since canoeing was an easier way to travel than traipsing through the cane. Now it is the other way around, walking is easier than paddling.

The land today's visitors see is very different from what Audubon beheld. Floods, earthquakes, the shifting rivers, agricultural practices and industrial development have all changed the area. Nothing is left of the Montgomery tavern where he stayed but the foundation. Even the size of the bayou-bound island where the town stood has diminished from erosion. There are no private residences or businesses there.

Even the plants have changed. Audubon and other naturalists of his generation reported that the most dominant species along the lower half of the Mississippi was cane, Arundinaria gigantea. This native bamboo formed an almost impenetrable barrier to foot travel.

Massive canebrakes extended for miles on each side of the river. According to Jerry Davis of Hot Springs, a former U.S. Forest Service biologist, this cane "provided roost and nest sites and endemic insects and when it flowered it provided tons of seeds per acre which was used by birds and people for food."

In a recent trip to the Arkansas Post area I could not find a single stalk of bamboo.

Eager to replicate some of Audubon's canoeing experiences near Arkansas Post, I tried to paddle a canoe in Moore Bayou and Post Bayou and down recently dug canals. It took 30 minutes to go less than 50 yards in some spots. Colonies of invasive water hyacinth have made boating impossible except in the deepest parts of open water.

Water hyacinth is to waterways what kudzu is to forests and fields. A South American plant introduced to the United States at the 1880 World's Fair in New Orleans, it was intended for aquariums and decorative pools. It escaped. By 1919 the overgrowth had become so detrimental in the lower Mississippi Valley and Florida that a bill was introduced in Congress to import hippopotami from Africa to control the plant. The bill failed, and no suitable alternative of plant control has yet emerged.

Hyacinth can grow quickly enough to reproduce itself every 16 days. The seeds remain viable for 28 years.

I soon gave up paddling to walk about along the cane-less banks of the waterways.

LIST CHECK

Today the National Park Service at Arkansas Post National Memorial displays a reproduction of Audubon's painting of the Traill's flycatcher sitting atop a sweet gum branch. The post also distributes a checklist of all the birds one would expect to see within 7 1/2 miles of the park. The list contains 289 species, many more than Audubon reported.

The ivory-billed woodpecker and Carolina parakeet are not on the checklist, but all of the others that Audubon saw are.

If his journals are to be trusted, he walked and traveled by boat at least 32 miles in and around Arkansas Post, so he had ample opportunity to see many more species than he mentioned. A few of the birds that are on the modern checklist -- cattle egret, European starling and house sparrow -- were introduced to America after Audubon's time. As common as they are today, they did not exist in his world.

The modern counterpart to Audubon's journal for serious birders is eBird. This computerized database allows any birder, anywhere, to enter information of bird sightings at any time. They enter the date, time of day and location of their sightings and how many individuals of each species of bird they see.

Over the past 14 years, eBird archives cite 114 bird species inside the 400-acre park. This is more than Audubon saw, but far fewer than expected, according to the park's bird checklist.

The eBird postings show no indication of the willow flycatcher at Arkansas Post between 2000 and this year, and the only Empidonax that has been reported is the Acadian flycatcher.

During my visit, I saw very few willows that might support the insects favored by the willow flycatcher.

Once abundant cypress and tupelo trees have been logged off, nearby wetlands drained and the Arkansas River channelized for navigation. All these changes coincide with the decline in the bird populations and the biodiversity Audubon witnessed at Arkansas Post.

Like sunrises and winter wind, the numbers of birds were so huge in Audubon's day that he and most of his peers considered the bounty of nature an endless commodity. Comparing what he saw to what we see today, we know that they were wrong.

ActiveStyle on 12/22/2014