Geraldean Johnson was in her early 20s when her husband left Clinton to fight in the Korean War. Now, 64 years later at age 87, she is finally about to see him return home.

She and her son, Larry Bolden, said they were notified Dec. 10 that the U.S. military had identified human remains that were their husband's and father's, U.S. Army Cpl. C.G. Bolden.

The office of U.S. Sen. John Boozman, R-Ark., confirmed Tuesday that a representative from the Army will meet with the family Jan. 16 in Clinton to provide more details on the identification.

When a possible identification is made, a representative from the military's Joint Prisoner of War/Missing in Action Accounting Command -- which has the task of identifying unaccounted-for Americans from past conflicts -- meets with the family in person, explained Sgt. 1st Class Shalleah Cooper, a spokesman for the Defense Prisoner of War/Missing Personnel Office.

If the family "accepts" the DNA match, the department will announce that the person has been accounted for. The remains will then be flown home from the identification laboratory at Hickam Air Force Base in Hawaii, and the deceased will be buried with full military honors, Cooper said.

But for Geraldean Johnson, whose first thought was to have C.G. home by what would have been his 88th birthday in January, the process is all a technicality.

"I kept thinking, 'They're going to find his remains someday.' And now they did," she said hours after receiving the call earlier this month. "It's unreal. It just seems like it's a different day."

Died in POW camp

C.G. Bolden, the youngest boy in a family of 11 children, was too young to see action during World War II. After that war, he was deployed to Germany on a "cleanup" mission, Johnson said, and he was looking forward to another opportunity for combat.

He signed up with the Army Reserve and was called on in September 1950, shortly after the Korean War started.

"They said if you sign up in the Reserve and another war breaks out, you'll get something a lot better," Johnson said. "Well, you see what he got."

Just months after her husband went overseas, Johnson bumped into Robert Bradley, a Clinton man who served with Bolden in Korea. As she tells it, Bradley told her that Bolden was missing and that Bradley had looked for him. She said he also related that he was told by higher-ranking soldiers not to tell the family.

"I went straight across the street to the Red Cross, and I started sending telegrams," Johnson said. "A few days later, a man came to the kitchen door with a telegram in his hand, telling me C.G. was missing in action."

The young mother of a 4-year-old son moved in with her parents. She checked the newspaper every morning for any piece of information that could tell her what had happened to her husband, and she often shut herself inside the outhouse in their pasture, where she would "pray and pray and pray."

Over the years, through resources from Prisoner of War/Missing in Action organizations and the tales of those who served with him, she was able to get an idea of what happened: Her husband, 22 at the time, was taken as a prisoner of war in January 1951 while fighting the enemy in South Korea. He was marched to a prison camp just south of North Korea's capital, Pyongyang, in what his wife had heard was "the coldest weather there ever was."

Johnson said the Army representative who called her Dec. 10 said Bolden is estimated to have died in late April 1951 at age 23.

Years after the military declared C.G. Bolden a prisoner of war and presumed him dead, a man showed up at the family's Clinton home and said he was with Bolden when he died.

"They had agreed that if something happened to one of them, that the one who lived would come back and tell their folks," Johnson said.

The man, who didn't give the family his name, told them a story that Bolden's widow accepted as the truth.

"He said C.G. leaned against this old building -- leaned against there and died," Johnson said. "It was only six months after he left home.

"C.G. had his little Bible with him he carried all the time," she continued. "They stripped him of his dog tags, but didn't take his Bible. They dug this big trench and put a lot of the dead in that trench stacked on top of each other. This man said he took that Bible and read his last rites out of it and put the Bible in the trench with him. Ain't that something?"

In the years that followed C.G. Bolden's departure, his older brother, Johnie, stepped into the role of "dad" for Larry. Bolden's widow moved to Conway, married Edward Johnson, and was widowed again. Larry grew up, married and had three daughters.

According to the American Battle Monuments Commission, C.G. Bolden was posthumously honored with seven awards: the Combat Infantryman Badge, the Prisoner of War Medal, the Korean Service Medal, the United Nations Service Medal, the National Defense Service Medal, the Korean Presidential Unit Citation and the Republic of Korea War Service Medal.

And then, about 15 years ago, the military asked for his siblings' DNA, reigniting the family's hope that he would still someday be found.

Johnie Bolden and Helen Ruth Isom -- C.G. Bolden's last living brother and sister at the time -- gave their DNA, which the Army representative said was used in making the identification, Johnson said.

Johnie, who Johnson said "always worried about his brother," died a few years later in April 2002.

"What I wish, I wish Uncle Johnie, who he was so close to, would have been here to see this," Larry Bolden said. "I would give anything to have him see this."

5th Arkansan to be ID'd

C.G. Bolden, a light weapons infantryman in the Army's 2nd Infantry Division, is the fifth Arkansan who disappeared during the Korean War to be identified. According to records from the Defense Prisoner of War/Missing Personnel Office, 7,868 Americans in the Korean War -- including 104 Arkansans -- remain unaccounted for as of the office's most recent reports.

Efforts to recover remains from South Korea are ongoing; however, the Joint Prisoner of War/Missing in Action Accounting Command has been suspended from operations in North Korea, where an estimated 5,500 of the missing are thought to be. In the spring of 2005, the Department of Defense deemed North Korea unsafe for U.S. personnel.

According to the Defense Prisoner of War/Missing Personnel Office, many of the Americans' remains in North Korea were, and are still, concentrated in certain areas that were once battlefields or POW camps. Like Bolden, many of the American prisoners are believed to have died in the winter of 1950-51, before there was a system of food delivery to the camps.

Soon after the fighting ended in 1953, North Korea returned the remains of more than 3,000 Americans as part of Operation Glory, an effort to transfer the remains of casualties at the end of the hostilities. The country exhumed and returned more remains from 1990 to 1994, when it sent to the United States 208 boxes estimated to hold the remains of 400 individuals, according to the office's website.

During 33 field activities in North Korea from 1996 until their suspension in 2005, the U.S. recovered approximately 220 more sets of remains, which are now being identified through DNA and other methods.

Burial plots together

Larry Bolden, now 68, was 3 when his father left Clinton.

He has only a few fleeting memories of C.G. Bolden, he said, and the one memento he hangs on to is a copy of the Clinton newspaper from 1952, which includes a front-page article about his father's death.

Mostly, he's happy for his mother, who was more sure than anyone that his father would be found.

"I really didn't think it would ever happen," Larry Bolden said. "After all these years, we have some good news. I think it means everything to my mother. She is getting on up in years, and I know this is something that she's very proud to see."

Traci Bolden, Larry Bolden's oldest daughter, was eating breakfast with Johnson at a Waffle House in Conway when her grandmother received the call notifying her about the DNA match.

After that, the two "cried and cried" all day, Traci Bolden said.

"It's bittersweet," she said. "It brings back a lot of memories for her."

From her grandmother, Traci Bolden has learned a little bit about the grandfather she never met. C.G. Bolden was a "sweet" man, she said. He was a Sunday School teacher, and he had a "really good personality, a really good smile."

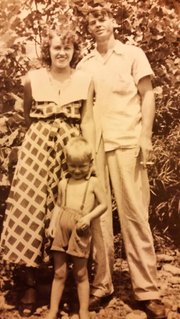

Proof of that smile sits framed in her living room: a photo of her 3-year-old dad standing between his smiling parents the summer before C.G. Bolden went to war.

Though re-examining the past has been hard for her the past two weeks, Johnson said she is looking forward to the future, to seeing her late husband's casket come off the plane and giving him a proper burial.

The first thing she wanted to do, she said, was trade in her single plot in the Clinton Cemetery for a double, so she and C.G. could be buried side by side.

"I always thought if they sent him back, I'm going to need a plot for two people," she said. "I got to go back to Clinton and hunt me another one."

A section on 12/25/2014