Before digitization, we sometimes used to wear out our records.

At least those of us with cheap audio equipment did. At one point I had three copies of The Beatles’ Revolver in various stages of decline. Cassette tapes were worse. At some point they’d snag and snarl and you’d have to try to spool the crinkly ribbon back up with a pencil through the take-up reel. Compact discs don’t last forever either, though I’ve got some that are 30 years old and sound as good as ever. (Which isn’t that great. While preferring vinyl to digital files might be mostly a hipster affectation, in the ’80s anyone with ears could detect the qualitative advantage of analog recordings.)

These days most of my music resides on a computer and I try to remember to back it up periodically. I should never have to buy another copy of Miles Davis’ Kind of Blue or T-Bone Burnett’s Proof Through the Night. I guess that’s nice, though I miss the old days when we had to hunt for obscure albums, when every out-of-town sortie included a stop in the local record store.

When you can dial up anything, nothing seems all that special.

Most of what I listen to is for professional reasons, which means listening to a lot of things one or two times before consigning it to the depths of the disk drive. Even without the migration to frictionless technologies, I probably haven’t worn out many records over the past 25 years.

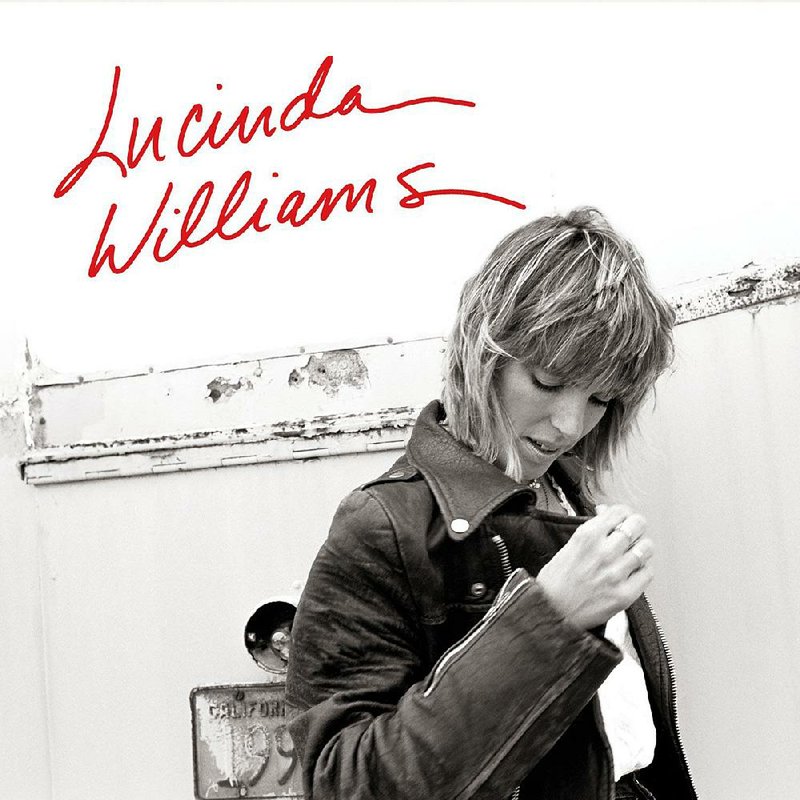

One I might have is Lucinda Williams’ self-titled record, colloquially known as “the white album,” or the Rough Trade album for the British punk label that released it in late 1988. I got a promotional LP just before it was released and a cassette tape a little later. If I remember correctly, a CD wasn’t immediately available, but I acquired one either just before or shortly after I moved to Little Rock in early 1989. I sold off the LP along with about 5,000 other albums (if that sounds shortsighted now, consider that I’d moved most of those albums six or seven times and the money was important to me). Somewhere along the way the cassette broke; I still have the CD.

I’d never heard of Williams before Lucinda Williams, so maybe it was natural that I’d assumed it was her debut. It was her third. She’d released Ramblin’, a collection of roots music covers (more blues and country than folk, but you could hear the skeins twisting around each other) for Smithsonian Folkways in 1979 and followed it up a year later with Happy Woman Blues, which was all original material (“Sharp Cutting Wings,” “Lafayette”) that only sounded like classic Americana. Then Williams cut some demos for Columbia and ran into a corporate wall. They didn’t get her lyrics, they didn’t get her voice. Major labels couldn’t figure out what to do with her - she was too country for Los Angeles, too rock for Nashville. She played clubs. She made her bones with other songwriters. She waited. Finally a British label gave her a chance.

I have memorized that album - the pop charge of the lead track “I Just Wanted to See You So Bad,” the cinematic “The Night’s Too Long,” the tough lament “Abandoned,” the counter-intuitive boppy twang of the kiss-off number “Big Red Sun Blues,” the vaguely Nick Drake flavor of “Like a Rose,” all the way through to the magnificently observed “Side of the Road” and the album closer, her benedictive reading of Howlin’ Wolf’s “I Asked for Water (He Gave Me Gasoline).” There’s not a weak link.

A star should have been born. But Rough Trade was in financial difficulty when it was released. They folded soon afterward. Lucinda Williams went out of print, but Koch re-released it in 1998 with some bonus live cuts. That record went out of print too. For the past decade or so, it’s been hard to get a copy of Lucinda Williams.

That was remedied in January with a 25th-anniversary edition released by Williams’ new independent label, Lucinda Williams Music. Remastered from the original master recordings, which had been missing for more than 20 years, the new package features a bonus disc containing an unreleased 1989 live concert recorded in Eindhoven, Netherlands, in which Williams and a pick-up band tear through the album’s songs, along with six previously released live bonus tracks. (The album is available at the usual outlets and through pledgemusic.com.) The expanded booklet includes two new sets of liner notes, one written by Rough Trade artists and repertoire man Robin Hurley and a second written by critic Chris Morris.

That this could have happened seems amazing to me, for Lucinda Williams is an all-time great album. Were I someone who liked to make lists of this kind, I’d include it in the Top 10 best pop-country-rock albums ever. It means as much to me as Van Morrison’s Astral Weeks or The Beatles’ Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band. It probably means more. Some of this is personal. I feel a connection to Williams - her father, poet Miller Williams, is a dear friend. But I was a Lucinda Williams fan before I met him (it was only after I came to know Miller that I realized Lucinda was his daughter).

When the album was released, it got a good (but not great) review in Rolling Stone. Bob Christgau gave it an A minus (which he later upgraded to an A) in the Village Voice. In the Voice’s 1989 Pazz & Jop poll, Lucinda Williams came in at No. 16, while an extended-play disc which contained “Passionate Kisses” and four live acoustic versions of other songs from the album was named the year’s best EP. Patty Loveless had a Top 20 Country hit with “The Night’s Too Long” in 1990. Tom Petty covered “Changed the Locks.” Emmylou Harris cut “Crescent City” and told the world that “just when you thought there were no more truths to be unearthed in the human heart, along comes Lucinda Williams, who plows up a whole new field.” Rosanne Cash invited Williams along as a special guest on her Austin City Limits appearance. Mary Chapin Carpenter’s cover of “Passionate Kisses” led to Williams winning a 1993 Grammy Award for best country song. In 2006, Spin magazine named it the 39th best album released between 1985 and 2005.

You couldn’t call the record a commercial hit, but it earned her a small but intensely loyal (and somewhat obsessive) following and a burgeoning reputation as a songwriter’s songwriter. RCA snapped Williams up, but when it presented her with sugary, radio-ready mixes of her new songs she told them “no thanks” and walked out on Elvis Presley’s old label. Her father tells the story this way: “One of the RCA execs stood up and said to her: ‘Young lady, no one has ever walked out on an RCA contract’ and she said, ‘Well, you can’t say that anymore.’”

Those tracks surfaced, mixed Williams’ way, as Sweet Old World on Chameleon, another small and ill-fated label. And six years after that, Car Wheels on a Gravel Road finally made Williams a genuine pop star.

I love all her records to varying degrees. Williams has been a constant presence in my life since 1988; I doubt I’ve ever gone more than a week or so without returning to the Rough Trade album.

I haven’t worn it out yet.

blooddirtangels.com

Style, Pages 47 on 02/23/2014