When Frankie Pratt, chief executive officer at Little River Bank in Lepanto, began his 47-year banking career, he was an examiner with the Federal Deposit Insurance Corp. carrying two brown booklets filled with banking regulations.

Those brown booklets couldn’t hold laws guiding banks today, said Pratt, who began working for the FDIC in 1966.

“The mountain of regulations is costing the smaller banks,” said Pratt, 69, who began a career in banking after an almost 16-year career with the FDIC.

Those costs could be a catalyst forcing many small, rural banks in Arkansas and around the country to sell, banking experts say.

“In the long term, it will be more expensive to comply with regulations,” said Candace Franks, commissioner of the Arkansas State Bank Department. “It’s also hard to attract the kind of employees you need in rural areas to staff your institutions with the kind of challenges they need to keep up with those regulations.”

The Dodd-Frank Act, which Congress passed in 2010, mandates sweeping regulatory changes for banks. And regulations are updated and modified frequently.

“Prior to the financial crisis, the tendency was to favor free-market activity,” said Julie Stackhouse, senior vice president with the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis. “Post financial crisis, there is a much stronger eye on consumer protection. And that consumer protection is costly to banking organizations.”

Some banks in rural areas also are facing generational challenges, Franks said. Sometimes relatives aren’t interested in returning home to work in the bank, Franks said.

“So I think you’re going to see some sales and consolidation because of that,” Franks said. “And I think that it will be a challenge to find buyers.”

A survey conducted last year by KPMG, a national audit, tax and advisory firm, showed that about 25 percent of bankers surveyed said it is likely their bank would be sold this year. KPMG surveyed 105 chief executive officers and senior executives at banks.

Robert Ulrey, managing director in charge of investment banking for banks and savings and loans at Stephens Inc., doesn’t expect a quarter of the banks in Arkansas will be forced to sell this year.

“It’s hard to project,” Ulrey said. “Obviously we’ve had a period where there have been [Federal Deposit Insurance Corp.] assisted deals going on. That partially sucked up demand from the buyers.”

Since 2008, the federal government has sold or closed about 500 failed banks in the country.

If 25 percent of the country’s banks sold this year, the number of banks would shrink from about 6,900 to almost 5,200.

Bankers have been predicting a flood of banking acquisitions over the past several years, John Depman, national leader of Regional and Community Banking at KPMG, said in a prepared statement discussing the survey.

“But it’s been more like a steady drip,” Depman said. “The fact is that it’s tough to get a deal done. The bid-ask price spread, the regulatory environment and targets’ balance sheet issues are all real challenges to overcome.”

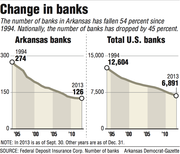

Even before regulations increased, the number of banks nationally was falling. In the past 20 years, the number of banks has declined 45 percent nationally, from 12,604 in 1994 to 6,891 last year. In Arkansas, the number of banks has fallen 54 percent, from 274 in 1994 to 126 last September. The drop isn’t only from banks being sold, many bank holding companies with multiple bank charters have combined them into one charter as a cost saving measure.

When all of the already announced acquisitions of the past few months close this year, there will be about 115 Arkansas-based banks in the state.

Garland Binns, a Little Rock attorney with the firm of Dover Dixon Horne, said he expects the sale of banks in the state to continue over the short term, which he defines as five years.

“Bigger banks want to get bigger,” Binns said. “The costs for small banks are about the same as for a $400 million [asset] bank.”

The effect on small towns could be significant, said Dominik Mjartan, senior vice president with Southern Bancorp Bank of Arkadelphia. Towns with only one or two locally based banks - such as DeWitt, Dumas, Helena-West Helena, Lake Village and Stuttgart - are the ones at the most risk, Mjartan said.

“If one of [the banks] goes away, maybe the other one can limp along for a little while,” Mjartan said. “But if they’re a $100 million to $200 million bank [or smaller], their chances of long-term viability is not great.”

Small rural banks that find it difficult to attract larger institutions to buy them may consider mergers of equals, Binns said.

One scenario is an older banker at a $100 million bank- with no one to succeed him - and a younger top executive at another $100 million bank, Binns said. Those banks aren’t marketable to the larger multibillion-dollar asset banks that are making acquisitions, Binns said.

“There will be possibilities for banks to consolidate without one having control of the other,” Binns said. “It would be more of a partnership.”

Southern Bancorp, a community development bank, has a desire to fill the void when rural communities lose banks, Mjartan said. The bank’s primary mission is not making money for its stockholders but developing the economy of the rural areas it serves. It has branches in Arkadelphia, Blytheville, El Dorado and Helena-West Helena, among other towns in Arkansas and Mississippi.

Southern Bancorp, which has about $1.2 billion in assets, was formed in 1988 by the Winthrop Rockefeller Foundation. Its shareholders also include the Walton Family Foundation and Winrock International.

A major obstacle in Southern Bancorp’s plan to buy some of those small, rural banks is a lack of capital, Mjartan said. Southern Bancorp doesn’t want to take money from large Wall Street firms, Mjartan said, because those firms focus on getting returns on their investments.

“It’s our mission to serve those markets and we’re pretty good at it,” Mjartan said.

For three years, Pratt has been with Little River Bank, which has about $40 million in assets. The bank, with 14 employees and one office, operates on the edge of profitability, losing $62,000 last year and earning $92,000 in 2012.

The growing regulations forced Little River Bank to hire a full-time compliance officer in 2012 to keep up with the laws, Pratt said.

Hiring that one employee could have pushed Little River Bank into losses, according to a report last year by the Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis.

The report estimates that the hiring of a part-time worker would cause 6 percent of banks with less than $50 million in assets to become unprofitable. An additional 33 percent of banks that size would become unprofitable if they had to hire two employees, the Minneapolis Federal Reserve said.

Hiring those workers is not easy for banks in rural areas, said Randy Dennis, president of DD&F Consulting Group, a Little Rock bank consulting firm.

“A lot of people don’t want to live in the Delta or in pine country,” Dennis said. “That’s the problem. It takes a level of sophistication to run a bank. But how do you hire managers in some of these rural areas? I don’t know the answer.”

Business, Pages 69 on 02/23/2014