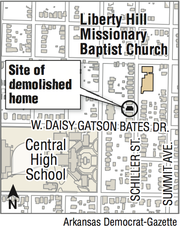

When leaders at Liberty Hill Missionary Baptist Church near Little Rock Central High School decided to tear down an old house on Schiller Street, the idea was simple: replace the aging structure with a green space to beautify a spot they saw as run-down.

One of several church-owned properties on the block, 1312 S. Schiller St. was a 1915 single-family home sitting within the bounds of the Central High School Neighborhood Historic District, an area listed on the National Register of Historic Places. Though the house was nearly a century-old, the city had no authority to halt a demolition.

Members of Central High Neighborhood Inc. -- one of the district's neighborhood associations -- were outraged when they learned the home would be demolished, especially after working with the city in 2009 on a design overlay district that some thought would protect properties such as the Schiller Street house.

The design overlay district -- a zoning tool to keep property owners' renovations similar to the neighborhood's historic architecture -- specifies things such as building materials, roof pitch and garage location, but it cannot stop demolition.

"There is no reason for tearing down a perfectly good house," said Gary Iverson, a neighborhood association member. "That house is part of a community, it's part of a block, and it's more than just up to [the church] to make that decision."

Liberty Hill's pastor, Frederick Haynes, said the church wants to help the area and has goals similar to the neighborhood association.

"Our vision may be different than their vision of the block," Haynes said. "But our goals, I believe, are the same: to make a better community."

The conflict in the Central High neighborhood highlights the complicated process of protecting Little Rock's historic buildings and the problem property owners face in trying to improve their neighborhood's image.

Around Central High, freshly restored homes share blocks with boarded-up houses deemed unsafe for habitation by the city -- 65 total across the historic district, according to the city's Neighborhood Programs Division. With more than 115,000 tourists visiting Central High last year, residents and the city strive to keep the neighborhood tidy and maintain its historic flavor.

The Central High district was designated in 1996. It is roughly bounded by West 12th and 14th streets to the north, Wright Avenue and Roosevelt Road to south, Dr. Martin Luther King Drive to the east, and Thayer and Schiller streets to the west.

To qualify for the National Register, a majority of buildings in a district must contribute to its historic value through factors such as age, architectural significance or relevance to a historic event or person. According to the National Park Service, in 2013, 588 of the Central High district's 1,064 buildings were contributing structures -- about 55 percent.

The house at 1312 S. Schiller St. was one of those structures.

If a district loses its National Register designation, residents can no longer access some financial incentives for rehabilitating historic homes, including a 25 percent Arkansas state income tax credit. While Little Rock has about 20 districts on the National Register, local legislation protects only one from demolition by property owners.

The MacArthur Park Historic District is a local ordinance historic district, meaning the city's Historic District Commission can stop demolition and has strict guidelines for renovations and new construction. Areas around the state Capitol and Governor's Mansion are also protected by the Capitol Zoning District Commission, a state authority that requires that major renovations and demolitions get commission approval.

Boyd Maher, executive director of the Capitol Zoning District Commission, said it takes a local ordinance to truly safeguard properties.

"If you have a historic home listed on the National Register and you want to tear it down, all they'll do is take it off the National Register," he said. "The great weakness of the design overlay district is it can't stop demolition. You can't zone someone to not demolish."

City government has made efforts to preserve homes around Central High. In 2009, Little Rock adopted by resolution a citywide historic preservation plan to guide policy in historic neighborhoods. A 2010 grant from the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development's Neighborhood Stabilization Program gave $8.6 million to rehabilitate or build at least 100 homes in the city, including around Central High.

Victor Turner, assistant director of the city's Housing and Neighborhood Programs Department, said program administrators work with a historic planner in areas such as the Central High district. He said an architect has begun making rehabilitation plans for a circa-1925 house at 1501 S. Summit St. that the city bought in 2010.

He said demolition and new construction around Central High is done in accord with the design overlay district, with an eye toward preservation.

"We're not going to demolish anything contributing to the historic district," he said. "We're sensitive to that."

But to Haynes, his church has an obligation to beautify the block, even through demolition. He said the Schiller Street house, in need of restoration, was an eyesore.

"When the house went into foreclosure, nobody seemed to be interested in the property," he said. "Once that house is torn down and the green grass is there, it's going to make the whole block look better."

A record from the Pulaski County Circuit Court clerk shows the church bought the property in November for $28,001 at auction. While church leaders considered preserving the house, Haynes said renovation estimates ranged from $89,000 to $100,000.

Demolition cost only $4,000, he said.

Haynes points to the church's other efforts to improve the visual appeal of the neighborhood. Donated property on Summit Street allowed the church to expand its parking lot and green space. A ministry uses a restored house owned by the church at 1320 S. Schiller St. as an office. Haynes and his wife, Janice Haynes, own homes at 1200 and 1210 S. Schiller St. and at 1226 S. Summit St., which they rent to neighborhood families.

"Yes, preserve the community," he said. "But in the process, we want to make the neighborhood look presentable."

Vanessa McKuin is the treasurer for Central High Neighborhood Inc. and executive director of the Historic Preservation Alliance of Arkansas. She and her husband just completed a five-year restoration of their historic home near Central High, living in its 400-square-foot carriage house during the renovations.

She said the neighborhood needs a clearer sense of direction in preserving its history, both through protective efforts by the city and better communication between neighbors.

"I completely can relate to the feeling that buildings that are in rough condition detract from the neighborhood, but I don't think the answer to beautification is to get rid of that building," she said. "I think it really speaks to the larger problem in our neighborhood, which is there's no larger vision for our neighborhood. ... We're losing a resource that is not renewable."

Metro on 07/13/2014