Tour Pearl S. Buck's home in Bucks County, Pa., and you'll feel as if you've discovered a treasure as prized as an oyster's pearl.

Layer after layer of Buck's story will peel away and inspire you as you go room to room, walk the grounds and visit her grave. A best-selling author, Buck was the first American woman to win the Nobel and Pulitzer prizes for literature. But her work went far beyond the printed page.

Buck counseled presidents, mothered a brood of children (one birth child, seven adopted children and at least 10 foster children), changed the lives of thousands more children and fought for racial harmony through cultural understanding. The daughter of missionaries, she used her vast knowledge of China, where she lived for 40 years, to bridge major gaps in understanding between the East and the West.

Beloved and admired, she also accepted keys to more than 30 cities, collected 13 honorary degrees and was featured on a postage stamp. She deserves as much admiration as other Bucks County luminaries, including Henry Chapman Mercer, James A. Michener and David Burpee.

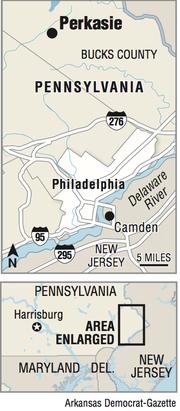

"We worry young people will not know who she is because The Good Earth is gone from most school reading lists," says Janet Mintzer, chief executive officer of Pearl S. Buck International, referring to Buck's famous novel about the lives of a Chinese peasant family. Buck, who died in 1973, was born in West Virginia 122 years ago, grew up in China and lived for nearly 40 years at Green Hills Farm in Hilltown Township near Perkasie.

To keep her memory alive, Pearl Buck International not only keeps up her home, but also offers a teen leadership program and summer culture camps for children. It also continues Buck's legacy of finding loving homes for children who need them via its Welcome House program and providing still more children and their families with health care, education and support through its Opportunity House.

Buck's house, itself, also was endangered, in disrepair and needing major work despite being one of only a few National Historic Sites focusing on a woman and even fewer containing an intact collection of her belongings.

NEW BOOK DISCOVERED

But times are looking up for Buck and her home. A new and previously unpublished manuscript has been discovered and published as The Eternal Wonder, stirring new interest in the author. The home was removed from a list of Pennsylvania's 10 most endangered historic houses and reopened in 2013, after eight years of extensive repairs and restoration.

Today, the 1825 stone farmhouse and surrounding 60 acres play a major role in telling Buck's story and continuing her legacy. Buck and her second husband, Richard Walsh, made major changes in the home to accommodate their large family and provide office space. But it never lost the appeal that made Buck fall in love with it the first time she saw it.

But how and why did Buck find her way to Bucks County?

Bucks County, already known for its peace and quiet, appealed to artists of all kinds. The property was within a few hours' drive of her New York publisher's office and also enabled Buck to be close to her only natural-born child, Carol, who had the progressive mental deterioration of phenylketonuria in a time when it was unknown. Carol lived at New Jersey's Vineland Training School from 1929 until her death in 1992.

Taking a guided tour of Buck's home opens doors to her world and offers more intimate glimpses of this woman who balanced career and children, long before women's liberationists tackled the issue.

Her weekday routine was fixed. After making sure the children were off to school, she'd write from 8:30 a.m. to 12:30 p.m. Then, she would spend the rest of the day running the household, helping the children with homework or teaching them other skills, including playing chess, the piano and the organ.

Although the author had help on weekdays (a housekeeper and a cook), she was on her own to mother her brood in the evenings, during the night and on weekends. She also cooked for the family on weekends, using recipes from two shelves of cookbooks still in the kitchen. "Pancakes were popular, but she also was fond of making roasted meats and vegetables fresh from the garden. Her favorite dessert was peach ice cream," says curator Donna Carcaci Rhodes.

Furnishings range from the sentimental, such as the deacon's bench from the John Day Publishing Co. where Buck was sitting when she first met future husband Walsh and learned he would publish her first novel, East Wind, West Wind, to the entirely practical -- a specially designed closet outside her bedroom containing equipment she needed to heat a child's bottle in the middle of the night. Decor also is cross-cultural, including many Chinese, Indian and Japanese pieces brought back from the Far East mingled with antique finds the Walshes made in Pennsylvania Dutch country.

The long table in the farmhouse kitchen is set with dishes and flatware Buck liked and used. Accompanying it are picnic table-style benches to accommodate the ever-changing number of children who gathered around it.

"No one really knows how many children she cared for over the years," the guide says. Besides adopting and fostering children, she sheltered others for a few weeks or months until permanent homes could be found for them. We've had a fair number of visitors tell us they were among those children."

One of the home's two libraries contains Buck's Good Earth desk and the secondhand, 1911 Royal typewriter she used while writing in the attic of her cottage on the grounds of the University of Nanking, where she and her first husband, John Lossing Buck, were teachers.

Among books crowded into the home's second library are a few left from a set of Charles Dickens works Buck read, over and over again, as a child growing up in China. She treasured them and credited the English author with inspiring her. In the month before she died, she asked to have the books brought to her and spread on her bed so she could see and hold them again.

The home's living room, where the idea for Pearl S. Buck International's "Welcome House" was born, is one of its most historically significant locations. The author invited influential friends, including Michener and Oscar Hammerstein, to help solve a problem she discovered in 1949.

She was asked to find a home for a biracial child and finally realized, after hours of calling, that no adoption agency would accept him for placement. She declared, "Every child deserves a home," and rallied friends to help her start her own adoption agency.

WHERE BUCK WROTE

Buck's office has so much to see, starting with a large picture window that gave her an inspiring view of the property. A high cupboard holds a fireproof file cabinet for storing her manuscripts. There's a Dictaphone made by Thomas Edison and a display of busts of four of Buck's children. Buck sculpted them in the room's second floor loft. The author's glasses and pencil holder rest on her writing desk, as if she has just gone to the next room to confer with her husband in his office. Rhodes adds, "Richard Walsh had a great deal of influence on Buck and the children as a husband and father but also played important roles as her editor and publisher and business partner."

The couple's large bedroom contains a bookcase with photos of their children, a dressing table with two portraits of Walsh, Buck's mother's sewing cabinet, a vanity with Buck's bottle of Oil of Olay and more. She and the children often sat by the room's cozy fireplace while she read them bedtime stories.

Although Buck died at her Vermont retreat, she wanted to be buried at Green Hills Farm. She specified it should be away from the children's play area and sheltered from view by pines and bamboo so it would not be distracting or upsetting to visitors.

A short walk from the drive leading to the visitors' center and her home, her grave's flat granite slab is etched with Chinese characters representing her name. Her English name is nearby, on a bronze placard set into a large boulder of Vermont granite. According to her wishes, the grave is in the West, facing the East.

For more information about visiting the Pearl S. Buck home, visit pearlsbuck.org or call (215) 249-0100.

Travel on 07/27/2014