"In the next five years there won't be no more moonshine liquor," southern Appalachia's legendary moonshiner Popcorn Sutton mutters, half to the camera, half to himself in the 2008 documentary The Last One. He smears gritty clay on a pile of flat rocks with long, knobby fingers as he builds his last still.

"It'll be a thing of the past. And I'll be dead before then, anyway, so it won't matter."

Today's moonshine would be unrecognizable to the backwoods bootlegger, who committed suicide March 16, 2009, to avoid prison time for his craft.

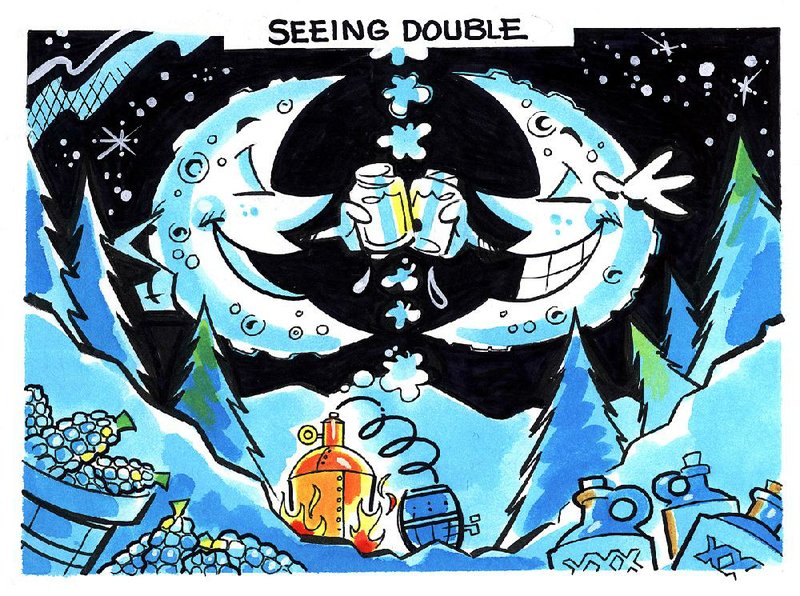

Glass jars and bottles glimmer with contents infused with cherries and other fruit flavors. Today's moonshine is branded with calculated charm: "hand-crafted" and "legacy" stamped in designer fonts. It's country-glamorous. It's Pinterest-stylish.

And it's legal.

Historically, moonshine's definition reflected its illegal origins. The Merriam-Webster Dictionary calls it "Untaxed liquor, either distilled or smuggled; so called from being made or removed at night." Moonshiners still distribute family recipes in the shadows of the Ozarks.

But in 2014, each of Arkansas' four distilleries produces unaged corn whiskey, federally regulated and taxed. This new beast is in a class of its own, marketed not for taste or quality, but with the remnants of a tantalizing taboo.

Tyler Lloyd, bartender at Little Rock's Studio

Theatre's Lobby Bar, runs his hands through delicately styled blond hair and laughs. People like the idea of moonshine because it's rough around the edges, he says.

Moonshine is unaged white whiskey.

"I think, technically, moonshine has to be made in a dry county by someone named Jethro."

The country is in the midst of a whiskey renaissance, says Frank Coleman, senior vice president of Washington-based Distilled Spirits Council of the United States.

American distilled spirits topped $66 billion in retail sales in 2013. Exports, which have been growing for almost a decade, surpassed $1.5 billion in 2013, driven by bourbon and Tennessee whiskey, which accounted for more than $1 billion of the total.

Supporting the trend are hundreds of new craft distilleries.

In 2001, the council tracked only a couple of dozen small distilleries in the United States. Now, Coleman says, there are easily 500 across the nation, with probably another 100 in planning stages. Moonshine is a practical product for newborn distilleries trying to get their feet off the ground.

"If you're new to the distilling business ... just from the economic standpoint you've got to get back some of your investment," he says. "One simple answer is to stick to unaged products: vodka, gin, unaged white rum."

The young distilleries found a willing crowd: the 18-25 age group, attracted to the idea of replicating a rebellion, Coleman says. They don't know what they're drinking, and blinded by thrill of taboo, they don't really care.

Rock Town Distillery founder Phil Brandon attributes moonshine's recent popularity to a re-emerging Prohibition-era aesthetic.

"The whole hipster generation thing, stylistically, really is a throwback to the 1920s," Brandon says. "I think moonshine is part of that whole cocktail culture."

Rock Town's corn whiskey, Arkansas Lightning, begins the same way its bourbon does: a grainy mash of corn, wheat and malted barley bubbling in enormous vats. The grains are ground, cooked and fermented. After three days, the sour, yeasty stew is pumped through the still. Once the alcohol has been extracted, Rock Town distills the liquid again and dilutes the whole batch down to bottling proof: 125.

Rock Town, in Little Rock, released the Arkansas Lightning line in 2011. Despite marketing quotes which play up the idea ("granddaddy used to make a little lightning every now and then"), Lightning is not technically moonshine, Brandon says, because it is legally made.

"Moonshine is a moniker for illegal whiskey or illegal spirits," Brandon says. "So it [moonshine] could be anything, right? Moonshine could be a whiskey, a rum, a vodka, a gin."

"Moonshine is just any stuff that's made in the hills," says bartender Darren Houston, wearing a backward baseball cap, at the Town Pump in Little Rock. He tried it once, but wouldn't repeat without adding Sprite.

"Closest I can compare it to is PGA [pure grain alcohol]," he says.

"I think it's more akin to the corn liquor," says Arkansas Alcoholic Beverage Control staff lawyer Mary Robin Casteel. She doesn't know exact ingredients, but to law enforcement that doesn't matter, she says. Owning an unlicensed operational still, regardless of what goes into it, is a Class D felony, punishable by up to six years in prison and a fine of up to $10,000.

Gary Taylor, owner of White River Distillery, Inc. in Gassville, says he obtained his permit because he didn't want a run-in with the local ABC agent, a figure he describes as a 6-foot-7-inch ex-Marine. Taylor's not looking to expand his business across the country or to begin producing other forms of alcohol. But he believes that with larger companies like Jim Beam and Budweiser being bought out by international corporations, people are more attracted to American-made alcohol.

"This country was founded on alcohol production," Taylor says. "What paid for the Revolutionary War? Tax and alcohol. George Washington was the biggest bootlegger of them all."

The number one complaint Taylor gets is that his moonshine, 90-proof Friday Night Redeye, isn't strong enough.

"I've taken it right out of the still at 150 proof and taken a shot," Taylor says. "It's not enjoyable. It burns all the way down."

On the back porch during intermission at an alternative film screening, Ron Walter scrunches his nose under dark-rimmed glasses. He tried moonshine, once. It burned his lips the moment it trickled from the jar.

"Tasted like rubbing alcohol," he said.

What is moonshine? "Drunk juice," Walter says.

Moonshine's reputation as "the strongest stuff you can drink" is often skewed, says Hayden Wyatt, who owns Arkansas Moonshine, Inc. in Newport.

"I've had no less than 10 different people bring me moonshine they've made," Wyatt says. "I can tell by the taste and smell it's made in traditional way. But all the stuff that's ever been brought to me, they say its 140 proof. I'll test it and it's 60."

Wyatt takes pride in the distillery, inherited from the late Ed Ward of Batesville, who obtained the first license to legally produce moonshine in Arkansas in 2010. But he has learned that with moonshine, Arkansans are more attracted to nostalgic mystique than taste or quality.

As a legal distiller, the allure of a forbidden fruit is lost on him; Wyatt says he prefers most other forms of alcohol.

"If I drink, I'll drink some whiskey or vodka."

Wyatt doesn't take a shine to 'shine.

Style on 07/27/2014