DARBANDIKHAN, Iraq -- As Sunni rebels advanced across Iraq in recent weeks, hundreds of thousands of Iraqis were driven from their homes. For many, it was not the first time.

RELATED ARTICLES

http://www.arkansas…">Iraq forces aim to oust militantshttp://www.arkansas…">Protesters raise fears in Jordanhttp://www.arkansas…">Islamic State use of social media in battle plans

There have been few prolonged periods of peace in Iraq over the past several decades, and for civilians seemingly perpetual flight. More than a million Iraqis have been displaced this year, half within the past couple of weeks, the United Nations said.

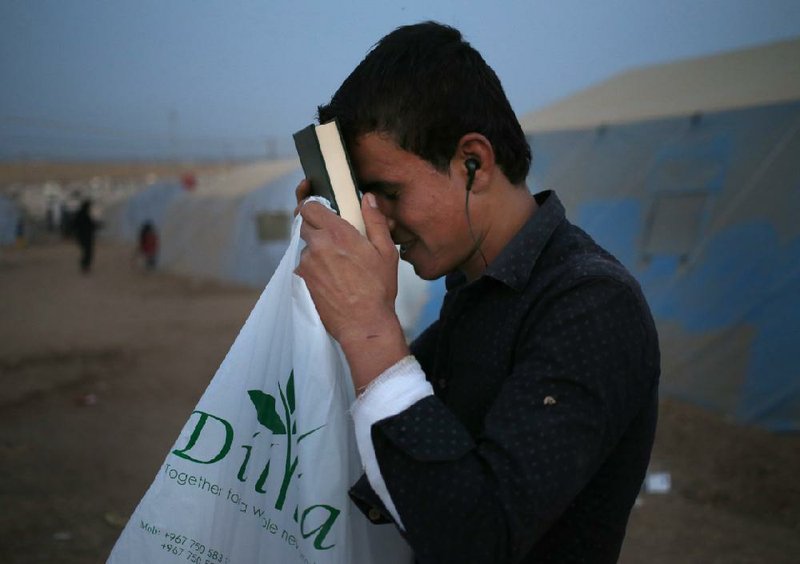

For Akheel Ahmed, a Sunni Arab who fled his home in the central Iraq town of Balad, fear and uncertainty were accompanied by familiarity. He arrived in Darbandikhan, a mountain village along the Iranian border, a few days ago with his three sons. It was the second time in recent years that he had become a refugee in his own country.

Using hand gestures, he described the battlefield that his hometown had become.

"Here is ISIS," he said, referring to another name for the Sunni militant group the Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant, "and here are the Shiite militias. We are in between."

He then checked off the names of his sons, to emphasize the urgency of his exodus.

"I have an Omar, an Othman and an Asha," he said, all recognizable as Sunni names, making them targets for the Shiite militias now working alongside the Iraqi army, he said. "They will slaughter them."

The rapid advances of the Islamic State and other Sunni militant groups across Iraq have increasingly merged the civil war in Syria and the violent Sunni uprising in Iraq into a single battle zone. Now, the humanitarian crises gripping both countries are converging. Millions of Syrians have already fled to Iraq, Jordan, Lebanon and Turkey, and now Iraqis are on the move, too.

Iraqis endured another refugee crisis after the U.S. invasion in 2003. In those years, many fled to Syria, but that is no longer an option. Jordan, another past destination for Iraqi refugees, is facing difficulty caring for the huge numbers of displaced Syrians.

"The situation is reaching a critical point," said a U.N. official who spoke on the condition of anonymity as a matter of official policy. "As bad as Syria is, the crisis [in Iraq] is growing by day and exceeding the capabilities of the government. Effectively, there is no centralized government over all of Iraq now, and in past years, they were already relatively weak."

This year, the United Nations appealed to donors for $106 million to care for nearly 500,000 civilians displaced from Anbar province, where militants began capturing territory in late December. Only a small portion of that amount was raised, and now the United Nations is planning to ask donors for another $312 million to face the new wave of displaced people.

Many of the displaced Iraqis have gone to the autonomous Kurdish region here in the north. Spread across the region are tens of thousands of Syrian refugees, some of them children who beg at traffic circles in the capital, Irbil.

The region, though relatively peaceful and prosperous, has been locked in a fight over oil revenue with Baghdad, which has cut its budget payments to the Kurdish government. That has produced a fiscal crisis and sharply limited the ability of the region to meet the refugee challenge. Kurdish leaders, while receiving praise for their open doors, are also wary of allowing too many Arabs into the territory, especially if they are single men of fighting age.

Iraq's Kurds have long been in conflict with the Arab populations over territory, and during the the current fighting have tried to expand their autonomous enclave and increase their control over it.

"They won't let me in because I am an Arab," said one man, near a checkpoint on the road between Irbil and Mosul, Iraq's second-largest city, which has been in the hands of militants for more than two weeks.

In Darbandikhan, most of the displaced are Sunni Arabs fleeing the militias or government airstrikes. They are angry over their present circumstances, but express deeper grievances, rooted in history, that leave little space for reconciliation between Iraq's Sunni minority and its Shiite majority.

Ahmed, reflecting a widely held belief in the country's Sunni population, said in defiance of the facts that his sect is a majority in Iraq. In many ways, Iraq's Sunnis have never accepted the new political order that came after the U.S. invasion, which forced out the Sunni-dominated government of Saddam Hussein and led, through democratic elections, to Shiite domination.

For a new leader of Iraq, he said, "We would accept a Kurd, a Christian or even a Jew."

But not, he said, a Shiite.

"They consider us infidels," he said. "And we consider them infidels."

Information for this article was contributed by Falih Hassan and Rod Nordland of The New York Times.

A Section on 06/29/2014