“It’s a natural. Black people suffer externally in this country. Jewish people suffer internally. The suffering is the fulcrum for the blues.” - Mike Bloomfield, as quoted by Al Kooper

“The white commercial songwriters were quicker to notice and imitate the spirit of the blues than their musical form … but in the Negro blues it is the gaiety that is feigned, while in the white it is the grief.”

- Abbe Niles, in the introduction to the 1949 revision of Handy’s Blues: An Anthology

The blues, like the past, is a shadowy territory of uncertain boundaries and ineffable depths. The poet Langston Hughes once complained that white folks had taken his blues and “fixed them - so they don’t sound like me.”Writer and artist Randall Lyon used to say white people could play the blues, we just don’t have to listen to them.

Anyone who has suffered through a bar’s all-comers-welcome blues jam knows that it’s not all that hard to work through a I-IV-V progression in 4/4 time. What’s hard is making people believe you feel it. The blues are like the ghost dance - it’s only as authentic as the hearts of its practitioners are pure.

To define the blues as an arrangement of sound, to set certain parameters to conceptually constrain the ideal trashes an essential emotive context. Yet if we define the blues as a profound musical expression of the anguish of American black people, a form forged in the brutal segregation of the late 19th-century Mississippi Delta - that genuine blues must arise from some reservoir of injury - aren’t we raising the specter of cultural separatism?

Maybe it is one thing to cherish a music, to tap into its primal stuff, its source materials, explore its conventions and ultimately use it to voice your personal joy and sorrow in a way that other people can relate to it. It is quite another to experience being born black in America, to know that your great-grandparents were born into slavery, to experience the subtle and overt forms of racial prejudice that still permeate this culture.

Music is more than an arrangement of sounds; that experiential, ingrained knowledge allows some folks access to deeper understandings.

On the other hand, blues has never been strictly the province of black folks. Blues was born during Reconstruction, at a time when black culture was forcibly insulated and spiritually charged. The black music that anticipated the blues, the work songs and field hollers of slaves, was the result of a mingling of African and European styles. Before the turn of the 20th century there was little difference between the popular music of blacks and whites in the rural South. It was only as forced segregation caused black people to further separate from white culture that a ballad style with its own code began to evolve, a form that in time came to be called the blues. But the wall between black and white was never impermeable; black musicians adopted the AAB structure of Celtic ballads - the first line was repeated, the third line different - as the basic structure of the blues:

If you see me comin’, better heist your window high

If you see me comin’, better heist your window high

If you see me going, baby, hang your head and cry

You might not have to be miserable to play the blues, but it helps. At least you ought to understand something of the trouble that gave birth to them. You probably ought to think of the blues as something more than just another genre invented to help consumers find the right bin in the record store or the right menu to pull down on eMusic.

“Never has a white man had the blues,” Leadbelly used to say, “because he ain’t never had the trouble.”

TROUBLE ALL IN THE WORLD I SEE

But Huddie Ledbetter didn’t live long enough to see Eric Clapton or Stevie Ray Vaughan or long enough to see the Weavers score a romantic pop hit with his suicide ballad “Goodnight Irene.” He didn’t live long enough to see Johnny Winter and Mike Bloomfield.

They had the trouble.

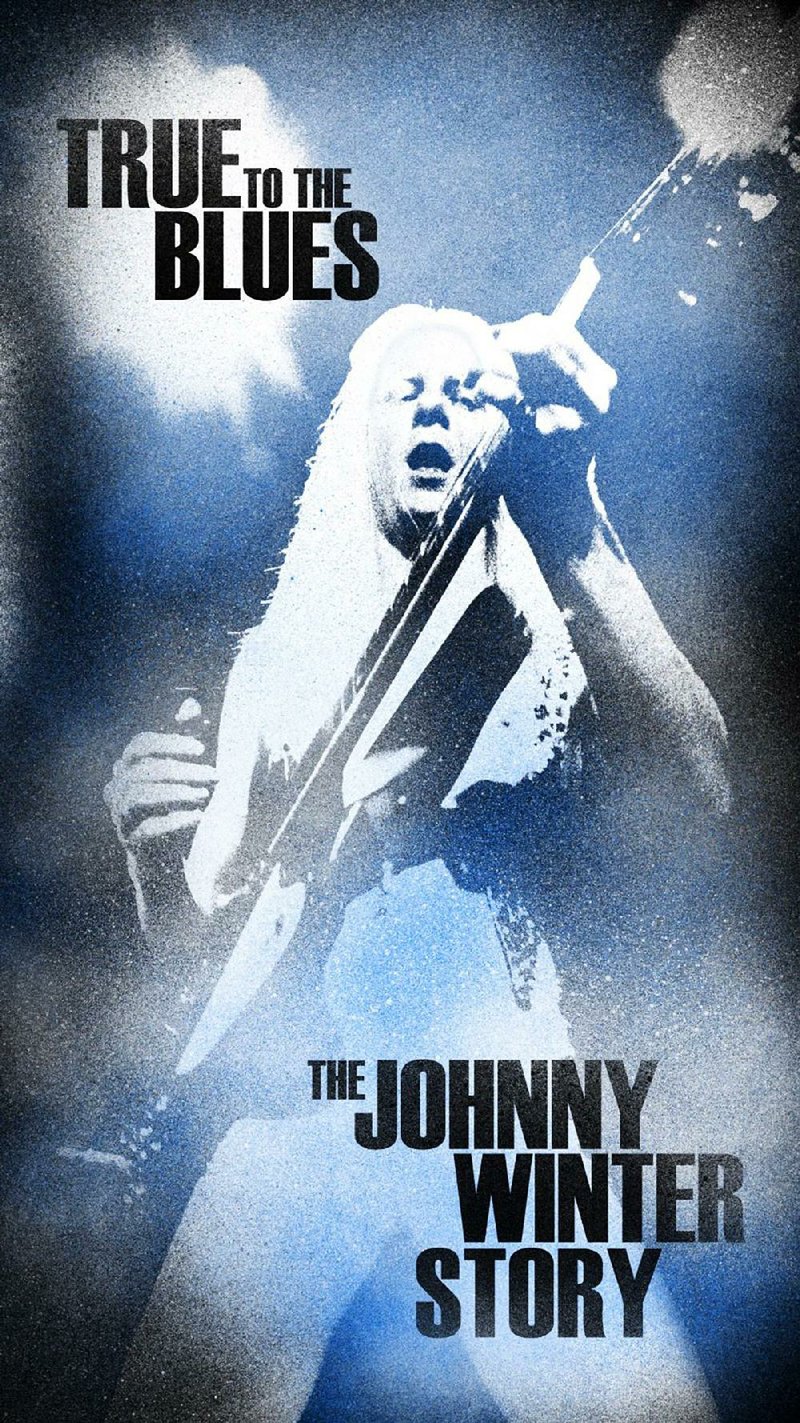

Boxed sets dedicated to Winter and Bloomfield are in stores now. True to the Blues: The Johnny Winter Story, a four-CD set comprising 56 tracks taken from 27 albums on several labels, spans Winter’s career. From His Head to His Heart to His Hands, a three-CD/one-DVD package, is devoted to Bloomfield’s truncated career. Both have been recently released by Columbia/Legacy.

If you still wonder if white folks can play the blues, then consider there’s no one whiter than Johnny Winter, the albino guitarist and vocalist who emerged from south Texas in the late ’60s. Winter, 70, is still touring and recording a new album. Step Back, a follow-up to 2011’s Roots, will reportedly feature guest appearances from Clapton, Dr. John, Mark Knopfler and other notables.As it turns out, Winter’s story is linked with Bloomfield’s. The Jewish kid from Chicago gave Winter his big break when, in December 1968, Bloomfield invited him onstage at New York’s Fillmore East to sing and play B.B. King’s “It’s My Own Fault” (a performance included in the new set). A friend of Columbia Records executive Clive Davis was in the audience that night. A few days later, Davis signed Winter to what was reportedly then the largest advance in the history of the recording industry-$600,000.

You can argue that Bloomfield’s star was already in decline by the time he introduced Winter at the Fillmore. Bloomfield, who had been part of the Chicago blues scene since his early teens, was offered a chance to join Bob Dylan’s band after his magnificent playing on “Like a Rolling Stone” and the Highway 61 Revisited sessions, but turned it down to continue playing with the Paul Butterfield Blues Band (which also included guitarist Elvin Bishop). He later founded the short-lived “American music” outfit Electric Flag before working with keyboardist Al Kooper (whom he met during the Dylan sessions) on Super Session, an album that was deliberately patterned after jazz albums of the period in which a leader (or co-leaders)would hire sidemen, pick a few tunes and record them over the course of a few days.

Kooper says Super Session was conceived in part to provide Bloomfield a setting conducive to his improvisational gifts. Kooper believed that - apart from the sessions with Dylan - Bloomfield’s studio work compared unfavorably with his incendiary live playing. (Even playing with the Butterfield Band, which apart from Highway 61 may be his most critically acclaimed work, Bloomfield at times seems to be holding back, content to play tasteful solos grounded in pentatonic - five note - scale.) Though Super Session would prove to be the most successful album of Bloomfield’s career, during its recording he was beginning to have problems with chronic insomnia, exacerbated by what his family believes was bipolar disorder. He only appears on side one of the record. Eventually his health caused him to withdraw and Stephen Stills was called in.

After that, Bloomfield cut an indifferent album that seemed to showcase his mediocre voice more than his playing (1969’s It’s Not Killing Me) and an ill-fated collaboration with John Hammond Jr. and Dr. John (1973’s Triumvirate), which in retrospect sounds like an album conceived by a record company executive desperate to squeeze some value out of an expiring contract. After that, Bloomfield was essentially out of the rock star business. He cut a lot of fine sides for Takoma; two rather endearing instructional LPs for Guitar Player magazine, The Root of Blues and If You Love These Blues, Play ’Em As You Please; and an inspired concert album - Live at the Old Waldorf. But he never really made much of an impression on the collective American consciousness again. He died at 37 under somewhat mysterious circumstances in 1981. His body was found in a parked car on a San Francisco side street and taken to the morgue as a John Doe. It was a few days before he was identified.

Meanwhile, Winter - whose growling rock voice married perfectly to his piercing, precise guitar attack - followed a somewhat similar if not so dramatic trajectory. His first Columbia album, Johnny Winter, featured the backing musicians with whom he had recorded in Texas: bassist Tommy Shannon and drummer Uncle John Turner, plus his younger brother Edgar Winter on keyboards and saxophone. (Willie Dixon played upright bass and Walter Horton added harmonica on “Mean Mistreater.”) The album also included Winter’s own “Dallas,” an acoustic number on which he played a steel-bodied resonator guitar; John Lee “Sonny Boy” Williamson’s “Good Morning Little School Girl” and B.B.King’s “Be Careful With A Fool.”

Winter’s version of the blues was something different from that applied by various British invaders. His solos were incisive and quick and, while charges of cultural appropriation can be (and have been) made, they retain the flavor of the original. Winter’s strain of blues flowed from Blind Lemon Jefferson’s needle-neat acoustic flourishes and bottom of the ocean howls through T-Bone Walker’s elegant electric glissando (and were echoed in the doomed bent-note shriek back of his follower Stevie Ray Vaughan).

Second Winter, recorded in Nashville in 1969, was a two disc album that had only three recorded sides (the fourth was blank). More importantly, it moved out of the fields with remarkable covers of Chuck Berry’s “Johnny B. Goode” and Dylan’s “Highway 61 Revisited.” (Another Bloomfield link: About this time Winter was having a brief affair with Janis Joplin while Bloomfield was helping her assemble her Kozmic Blues Band.) Winter moved more toward rock ’n’ roll, working with Rick Derringer and the rest of the McCoys (“Hang On Sloopy”) as Johnny Winter And. After a bout with heroin addiction, he came back in 1973 with a series of excellent records starting with Still Alive and Well. In 1977, he produced Muddy Waters’ Hard Again, which sparked a late career renaissance for the bluesman, but Winter never regained the commercial momentum of the first album.

SO MUCH TROUBLE FLOATING IN THE AIR

Can white people play the blues? Maybe that’s a needless provocation. It’s obvious white people do play the blues, and that some of them, like Winter and Bloomfield, have done it with credibility and even authority. Clapton humbly resists calling himself a “bluesman,” but has anyone ever played guitar with more economy and emotion?

Look at it another way, you might not take blues so seriously. After all, Leadbelly was a showman - he played reels and jigs, whatever would get people to dance. He was a “songster,” a human jukebox. The blues have always been malleable: W.C. Handy only heard “that weird music” a little over a century ago. Depending on your perspective, the blues - whatever it is - is dying young. Because, as Pete Townshend says, music must change.

Sure, the blues has been yanked from its original context and hijacked by artists who incompletely understood its cultural underpinnings. Sure, they play it for tourists in Chicago, New Orleans and Memphis. Sure, people think Dan Aykroyd and John Belushi started it.

There are holdouts. There are a few small labels - Alligator, Arhoolie, Black Top, Blind Pig, Fat Possum, High-Tone, Rounder, Yazoo - that still sell it. But “blues” is often a meaningless adjective, with little currency as a noun.

A guitar string doesn’t know who - or what - strikes it. If you are not superstitious, you understand it all comes down to vibrating columns of air. Intent and disposition have nothing to do with it; it is all physics.

But if you are not superstitious you cannot imagine the human soul, or the possibility of forgiveness, or even any reason for striking that guitar string in the first place. So maybe it does matter where you come from, what you have experienced and what you have lost. Maybe it even matters what trouble you’ve seen.

Email: pmartin@arkansasonline.com

blooddirtangels.com

Style, Pages 45 on 03/02/2014