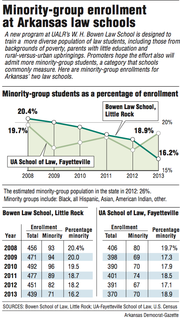

A program set to start this summer at Arkansas’ largest law school aims to offer a few prospective students from poor or disadvantaged backgrounds a second chance for admission to the W.H. Bowen School of Law at the University of Arkansas at Little Rock.

The Legal Education Advancement Program (LEAP) hopes to provide a dozen or so promising applicants who previously were denied admission a free, six-week training program in becoming better students.

Those who succeed will get a second look from the law school’s admissions committee. The best could gain entrance to the school this fall, said law school Dean Michael Hunter Schwartz, who launched the idea after joining the school July 1.

“Part of the goal is to capture those students whose [standardized test score and grade-point average] numbers do not accurately reflect their capabilities,” Schwartz said. “The larger goal is to serve Arkansas. There are communities in Arkansas - for example in the Delta region - that have among the lowest ratios of populations to lawyers in the entire country. As a result, they are not getting the legal services they need as communities.”

LEAP will be the only such effort at the state’s two law schools, say officials at the University of Arkansas School of Law at Fayetteville and the UALR law school. Both already take part in programs for disadvantaged students at the undergraduate level.

The UALR law school faculty voted overwhelmingly in January to implement LEAP, which stirred contention among some faculty and generated criticism on several conservative websites.

Among the questions:

Would LEAP overly emphasize race and risk failing court challenges? Courts have forbidden admissions based solely on that factor.

Would the program’s aim of accepting a handful of students with promising records but lower test scores and grade averages hurt the school’s national ranking?

The LEAP course aims to attract students with standardized test scores and grade-point averages too low to gain admission through regular channels, but who are outstanding in other areas such as leadership, writing, work experience or overcoming difficulties.

Experts who administer the standardized Law School Admission Test “have complained for years that law schools rely too much on LSAT scores and undergraduate grades,” Schwartz said.

And experts say the test is only about a 30 percent predictor of a student’s success. LEAP allows a candidate “a chance to say, ‘My scores don’t accurately predict my capabilities,’” he said.

For the initial effort this summer, the law school is inviting students who were denied admission since fall. Interested invitees would have to apply by April 1.

Those who are admitted to LEAP then will have to impress Schwartz and associate professor Terrence Cain, who will teach this summer’s session. Students who succeed in the summer would get a chance to persuade the admissions committee to admit them to the law school.

Schwartz envisions 10 to 14 students in the first LEAP session.

“We don’t have any projection as to the number of students who might be successful,” Schwartz said. “It’s all in whether they perform.”

UALR law school Associate Dean Theresa Beiner said she has no doubt LEAP passes constitutional tests.

“As a general matter, you can consider race among other factors for admissions,” said Beiner, who teaches constitutional law. “But [LEAP] is a race-neutral program. It is looking at [other] areas that are underrepresented, such as applicants from rural parts of the state … .”

She and Schwartz point out that LEAP is modeled on similar efforts by the nonprofit Posse Foundation of New York, which identifies public high school students “with extraordinary academic and leadership potential who may be overlooked by traditional college selection processes,” according to its website.

Another model is the Council on Legal Education Opportunity in Maryland, a nonprofit where Schwartz formerly worked as an academic curriculum consultant.

“It’s not like we’re doing something outlandish in the world of higher education,” Beiner said.

Jenifer Finney, assistant dean for admissions and scholarships at the law school, helped design the LEAP program and says the controversy is undeserved.

Because she works in admissions, Finney said, she hears “from the applicants who are denied … I hear how the [standardized] test scores or undergraduate grade points aren’t indicative of what they can do.”

But she knows the American Bar Association also requires law schools to admit only students who can successfully complete their studies.

“So it’s also our responsibility not to take their money knowing they’re likely to flunk out of law school,” she said.

Finney says it’s too early to predict the effect of LEAP on standardized test scores for next year’s class, but she looked backward and calculated the effect of adding 14 more students with lower scores than anyone in the current first-year class, which has about 139 full-time students.

“I did a spreadsheet just to see … That class still had the same median scores,” she said.

One of the biggest questions about the new LEAP program is whether it will be effective, especially in attracting lawyers to under served areas of the state, including rural, high-poverty counties in the Mississippi River Delta.

Across the nation, attorneys tend to practice in cities. The attractions include more professional opportunities, several choices for housing, higher pay, and amenities such as restaurants and entertainment.

That creates problems for rural dwellers, especially if they’re poor.

“It’s an access to justice issue,” said Cliff McKinney, a Little Rock attorney who has worked on a study for the Arkansas Bar Association’s Young Lawyers Section.

The state will appoint an attorney for anyone charged with a felony who can’t afford a lawyer, but there’s no such requirement for people facing most civil issues, including divorce, child custody and home foreclosure, McKinney said.

“If your family law case isn’t properly handled, you can lose child visitation rights,” McKinney said. “If it’s a paternity matter, someone who might owe child support may not pay or pay their fair share.”

The Young Lawyers Section study shows Arkansas with 2.04 attorneys per 1,000 people. The national average is 4.11. And the per-person rate in Arkansas’ rural counties is far lower. In the state’s 25 most rural counties, the highest concentration of attorneys in any of them is 1.38 per 1,000 residents. The average for rural counties was 0.72.

Schwartz acknowledges there’s little his law school can do to redirect graduates to under served areas, but he and others hope to graduate more attorneys who were raised in impoverished areas and might move back there.

Schwartz hopes legislators can be persuaded soon to finance a program to repay college loans for lawyers who serve in poor areas for a period of time.

“In the long run, I’m hoping I can also raise funds for a program like that from private donors,” Schwartz said. “Once I show we are admitting people, they’re succeeding and passing bar exams, I’ll have a much better case to make for private support.”

Arkansas, Pages 9 on 03/08/2014