Crude oil shipments through Arkansas aren’t regularly monitored by the state’s environmental, transportation and emergency responders even as the numbers of rail cars carrying oil south to Gulf Coast refineries are on the rise in Arkansas and around the nation.

Spokesmen for the Arkansas Department of Emergency Management, the Department of Environmental Quality and the Arkansas Highway and Transportation Department all said that the responsibility for rail car safety and content inspections belongs to federal authorities, mainly with the Federal Railroad Administration.

“The only time we get involved is if there’s an incident and the locals request resources,” said Kenny Harmon, manager of the Hazardous Materials Program for the state Emergency Management Department.

Exactly how much crude is moving by rail through Arkansas is known only by the railroads, which consider the information proprietary for competitive reasons as well as security. With the surge in oil production in North Dakota’s Bakken Shale, as well as the oil sands of Alberta, Canada, producers are relying heavily on rail since pipelines can’t handle the demand.

While spokesmen for the state’s two biggest railroads, Union Pacific Corp. and BNSF Railway, confirmed the shipments occur, they also said the railroads are actively taking steps to improve safety in the wake of three accidents involving tank cars carrying crude - one in a Canadian province and two in the U.S.

On Feb. 21, the U.S. Department of Transportation sent a letter to the Association of American Railroads, which represents U.S. railroads, outlining an eight-point plan requiring railroads that transport crude oil to do things such as analyze routes, impose speed limits and increase track and mechanical inspections, as well as inventory “emergency response resources,” develop contacts along routes and work more closely with communities to address specific safety concerns.

The Transportation Department created the plan in response to a sharp increase in the number of rail tank cars being used to transport crude oil around the nation, as well as several accidents that have resulted in crude oil spills, fires and fatalities in recent months.

Four days later, the DOT also issued an emergency order requiring shippers to test crude oil and properly classify crude oil to ensure that it is placed in the right kind of tank car for shipment.

Concerns about the safety of crude oil shipments have spiked in recent months after three fiery derailments. On July 6, 2013, 47 people died when several tank cars carrying crude derailed in Lac Megantic, Quebec. On Nov. 8, a derailment in Aliceville, Ala., resulted in an intense fire and spilled about 748,000 gallons of crude. And a Dec. 30fire broke out after cars from a BNSF train derailed near Casselton, N.D., spilling about 475,000 gallons of crude.

Kevin Thompson, a spokesman for the Federal Railroad Administration, which is responsible for inspecting and monitoring rail safety, said about 30 states conduct their own rail inspections as part of the federal “Rail State Safety Participation Program.” Arkansas does not participate in the program, he said.

Thompson said his agency, along with the federal Pipeline and Hazardous Materials Safety Administration, retains jurisdiction over setting and enforcing safety standards.

“It’s our preference to have a state as a partner in doing this sort of inspection,” Thompson said. “The federal activity would always be more dominant because we would have more inspectors than most states would have.” Federal efforts include both actual equipment inspections as well as audits of safety reports filed by the railroads.

State-run rail safety programs involve a multi-year agreement with the Federal Railroad Administration, allowing state inspectors to monitor and investigate potential violations of federal rail safety laws. The administration helps cover the cost to train inspectors, as well as provides on-the-job training, which emphasizes “planned, routing compliance inspections.”

States adjacent to Arkansas with their own inspection programs include Mississippi, Missouri, Tennessee and Texas.

The Association of American Railroads, based in Washington, D.C., estimates that nationally, about 92,000 tank cars are used to move flammable liquids, of which about 78,000 need to be retrofitted to meet updated safety standards or phased out. A tank car holds about 30,000 gallons, or more than 714 42-gallon barrels of oil, and are typically connected in what is called “unit trains” of 50 to 120 or more cars that are used to ship a single commodity.

In a March 13 report on crude oil shipments by rail, the association said that 434,042 carloads were shipped nationally in 2013 - nearly double the 234,000 carloads shipped in 2012.

Typically, the tank cars used to ship crude are owned by leasing companies or the shippers.

Railroads are working to phase out the use of older DOT-111 cars used to ship crude. The industry adopted tougher tank car standards in October, 2011, which include thicker steel shells, extra shielding at both ends of the car, additional protection for top fittings and improved pressure relief valves.

While they don’t actively monitor crude oil shipments, state officials are trained to respond to rail emergencies, such as a derailments involving hazardous materials.

Harmon said that while there is a greater awareness of crude oil issues, it’s just one of many training areas.

Katherine Benenati, a spokesman for the state Environmental Quality Department, agreed, saying that agency employees train on a regular basis with Emergency Management employees and other emergency responders from around the state.

“ADEQ emergency response officials work closely with our counterparts at ADEM as well as local officials around the state on such responses,” Benenati wrote in an email. “Those responses also have us coordinate with responsible parties.”

The training includes refresher courses on hazardous materials, which include crude oil.

Randy Ort, spokesman for the Arkansas Highway and Transportation Department, said that while the department works with individual railroad companies and the Federal Highway Administration regarding railroad crossing safety issues, it doesn’t monitor cargos.

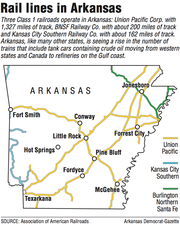

Arkansas is served by three Class 1 railroads, according to the Association of American Railroads.

The largest, Union Pacific Railroad Co., operates on 1,327 miles of track that connect Little Rock and Pine Bluff with Fort Smith, Texarkana, West Memphis and northeast Arkansas. It also has a locomotive repair and assembly shop as well as a rail classification yard in North Little Rock.

Burlington Northern Santa Fe Co. owns less than 200 miles of track concentrated in northeast Arkansas. UP and BNSF have trackage rights over portions of each other’s networks.

“BNSF strongly supports the new voluntary commitments to further reduce risk in the movement of crude oil by rail,” said spokesman Joseph Faust in an email. “The rail and petroleum industries, and U.S. Department of Transportation agencies have agreed to undertake several major actions to ensure shipping crude oil and other flammable liquids by rail is safe.”

Faust said BNSF is soliciting bids for 5,000 “Next Generation” tank cars. Two Canadian-based railroads are imposing a surcharge on shippers who use older tank cars.

Railroads, including Union Pacific and BNSF, have committed to providing $5 million in 2014 to develop a specialized crude-by-rail-related training and tuition assistance program for local first responders, said Union Pacific spokesman Raquel Espinoza. UP and other railroads are also developing a comprehensive emergency response resource inventory, but there is no specific time frame for it to be completed, she said.

Union Pacific annually trains about 2,500 local, state and federal first-responders on ways to handle a derailment, Espinoza said in an email. The sessions include training on tank car anatomy, hazmat shipping documentation and locomotive safety.

North Little Rock Fire Department Battalion Chief Phil Pounders said crude oil shipments are just one of many hazardous cargos that emergency responders must prepare for in the event of an accident. He said that while railroads such as Union Pacific routinely contact departments about derailments or other accidents, he doesn’t believe the department needs to be involved in pre-shipment monitoring.

“Canada shows what can happen in an event that’s out of the ordinary. But crude oil is not the only hazardous material shipped through here,” Pounder said. Hazardous materials training involves a variety of scenarios, including rail and truck accidents and familiarity with the containers holding the material.

As far as oversight, ensuring the cargo is in a proper container, inspected and correctly labeled, is handled by other agencies, Pounders said. “There’s really no point of us going down there and just sitting in the rail yard and counting cars or saying, ‘Ooh, that could spill.’”

Business, Pages 73 on 03/23/2014