Each night, Vernon Holden sent up a prayer from the Arkansas prison in which he was incarcerated: Please, God, take care of my kids. Help them find a good home.

Far away, in the little town of Alma, three little girls also prayed each evening at bedtime: Take care of our daddies, wherever they are. And please take care of our mom, too.

The girls shared a mother. But at least one -- maybe two -- of the sisters had different dads. Their parents' rights had been terminated.

The sisters lived with their adoptive parents Clay and Becky Warnock, now both 58. The Warnocks encouraged the girls to pray daily for their biological parents.

Clay often thought of Malachi 4:6 when pondering his daughters' situation: "And he shall turn the heart of the fathers to the children, and the heart of the children to their fathers, lest I come and smite the earth with a curse."

Clay didn't know much about his youngest daughter's biological dad -- only that his name was Vernon Holden and that he was locked up somewhere in a state prison.

Clay had been told that this same Vernon Holden also had fathered the middle sister. But the oldest girl cast doubt on this assertion, saying that no one really knew for sure.

Nine years after the Warnocks took in the girls, Clay felt called by God to minister to inmates. So in September 2012, he went with two friends to the J. Aaron Hawkins Sr. Center, a state prison in Wrightsville.

The three men had agreed to participate in a Christian program there. The program, Pathway to Freedom, prepares male inmates for their eventual release from prison. It also uses mentors -- like Clay and his friends -- to help newly paroled men reintegrate into society.

When the trio arrived at the prison, they learned there would be a church service before everyone broke into small groups.

Clay managed to snag a seat in the second row of chairs that had been set up for the service.

A few minutes later, a group of inmates filed in, claiming seats in the front row. The prisoner sitting directly in front of Warnock turned around and shook Warnock's hand.

"Hi," the inmate said. "My name is Vernon."

Vernon's story

Vernon Holden's marriage was a turbulent union. Sometimes, the fights turned physical and Vernon was arrested.

When the couple wed, Vernon's wife already had a daughter -- Daliesha -- from another relationship. The Holdens soon added two more girls to the family: Eve and Lillie.

Over the years, Vernon picked up several assault and drug charges. He spent a lot of time in jail, so he didn't see much of his children.

When he was around, Vernon would watch movies with the three girls. The Lion King was a particular favorite, mainly because Vernon sang along with all of the songs. His daughters found that hilarious, he said.

The first time Vernon went to prison, the younger girls were barely toddling. They weren't much older when he was sentenced yet again.

During one of his two stints in lockup, Vernon participated in a program targeting domestic violence and anger management. He did so because the Department of Human Services told him to.

The agency had been keeping an eye on the troubled family, said Vernon, now 45. Part of the problem was Vernon's numerous arrests and jail bookings.

The children were put into foster care after a family member left them unattended in her second-story apartment. The younger girls, still toddlers at the time, crawled out an open window and toppled onto an awning below, Vernon said, prompting a neighbor to call the state's Human Services Department.

The investigators who arrived grew even more disturbed when they couldn't get anyone to answer the door.

Vernon thinks his wife was able to get the kids out of foster care at some point. But he had no idea what happened to his daughters after that -- until the letter from Human Services arrived in the prison mail.

The letter said the agency intended to seek the termination of Vernon and his wife's parental rights.

"Wasn't nothing I could do about it," he recalls now.

Nothing, that is, except pray, and Vernon was doing a lot of that since being accepted into the Pathway to Freedom program.

Inmates in the program spend all day and most of the evening in classes or worship. They're not allowed to watch television because it's a distraction. Instead, these inmates must focus on themselves -- their pasts and their futures, their spouses and children.

Vernon applied to the program on a whim. Nothing else had worked out for him. Maybe it was time to try God.

"I was just looking for something different," he said. "I felt I could make it through that program."

Vernon didn't mind the long days or lack of television. He realized he needed this kind of setting to "get himself together," especially if he wanted to make it in the free world this time.

Occasionally, he heard from his wife, who was appealing the termination of her parental rights. She offered brief dispatches about their daughters, but offered no clues to their whereabouts.

Lord, if it's your will, let me see my kids, Vernon prayed. Please let them be in a good place with good people.

Clay's story

In 2002, Clay Warnock and his wife, Becky, decided that their nest was too empty. Their three children were adults and had long since left the couple's Alma home.

The Warnocks decided that fostering kids would be a good way to fill their house with the sounds of children that they so missed. And they knew that there was a desperate need for foster parents.

Becky was a first-grade teacher, and Clay worked in real estate. Still, they were certain they had the time and energy to devote to young children.

When filling out forms, the couple left one portion blank. It was the part: "Who We Would Not Accept."

"We just trusted that whoever God wanted us to have, we would have," Clay said.

In July 2003, the Warnocks opened their home to foster children. Several kids later, the call came: Could they take in two young sisters?

There also was a third sibling -- an older sister -- but she had been placed elsewhere.

Clay called his wife and asked her what she thought.

"Absolutely," Becky said.

Lillie was nearly 2. Eve was 3.

The Warnocks often invited the girls' older sister, Daliesha, 12, over for visits. "When the visits were over, the younger girls were just heartbroken," Clay said.

Soon, the state closed the foster home where Daliesha had been living. So the Warnocks agreed to foster her, too. But they knew this would be only a temporary situation because Daliesha had asked to be placed separately from her much younger sisters.

This puzzled Clay. The three girls had such a loving relationship.

One day, he pulled Daliesha aside.

"Can you tell me why you don't want to be in the same home as your sisters?" he asked.

Daliesha told him that before going into foster care, she had spent the last few years as the primary caregiver for her little sisters.

"I just wanted a chance to be a kid," she explained.

"I'll make you a promise," Clay said. "You stay with your sisters, and we will never make you have to be their mom again."

Daliesha agreed to stay.

A few years later, in 2006, the Warnocks learned that the girls wouldn't be returned to their parents -- ever. The Holdens' parental rights had been terminated.

The Warnocks had never planned to adopt children. But when Human Services officials told the couple that the girls wouldn't be going home, Clay and Becky had the same reaction: "They are home."

"We just knew they needed to stay together," Clay said. "And we already loved them."

The adoption was finalized in 2008.

In 2011, the Warnocks decided to stop fostering additional children. They felt that their three girls needed stability and consistency -- a normal and uneventful family life.

With that decision made, Clay figured he needed to find another way to give back to society. Now retired, he certainly had the time.

In 2012, Clay approached a friend who volunteered as an associate chaplain at the Crawford County jail.

"Bryan, could I go to jail with you sometime?" Clay asked.

That's when Bryan Tabakian told Clay about the Pathway to Freedom program and how it needed mentors for inmates who were about to be paroled.

So in September 2012, they drove to Wrightsville to learn about the program.

And that's when Vernon Holden turned around from his seat in the front row and introduced himself to Clay.

A chance encounter

"My name is Vernon," he said.

Clay glanced at the inmates' attire. The name "Holden" was printed on the left side.

Still, he had to ask. Surely it couldn't be.

"What's your last name?"

"Holden."

At that moment, the chapel service began.

Clay sat there, stunned.

Later, after the service, he tapped the inmate on the shoulder.

"Vernon?"

The inmate grinned. "You remembered my name."

"Yeah," Clay said. "I'm thinking you and me are about to become really good friends. Your daughter, Lillie -- I fostered and adopted her."

"What about Eve?" Vernon asked.

"We adopted her, too. We weren't sure if you were her father."

"Eve's my daughter, too," Vernon confirmed, thumping his chest for emphasis.

Clay had just enough time to tell Vernon that Daliesha also was part of their family before Vernon had to return to his barracks.

Vernon cried as he and the other inmates filed out.

"What's wrong?" they asked him.

Vernon told them what had just happened. His story circulated rapid-fire throughout the barracks.

For the inmates, Vernon's encounter with Clay was confirmation of what they had learned during the 18-month Pathway to Freedom program: God makes his presence known in prison.

A new normal

On the way home that day, Clay called his wife and told her what had happened. Becky was shocked.

"Is it OK, if I go ahead and tell the girls?" he asked.

"Well, of course," Becky replied.

That night, Clay sat down in the living room with Lillie and Eve.

"The prayer you've been praying -- well, God showed me today that he was listening. He introduced me to your dad, and he showed me that Vernon is saved and that he has a relationship with Jesus."

Clay continued: "Eve, Vernon's your dad, too. He still loves y'all. He misses you, and he wants to be part of your life."

Vernon paroled out of prison in March 2013 and returned to Fort Smith. Clay and another man in the area served as Vernon's mentors after his release.

A month later, Vernon saw his daughters for the first time since they were toddlers. Lillie was almost 11; Eve almost 13. They met at Clay and Becky's church to watch a concert featuring orphans from Uganda.

Vernon felt such joy, knowing that his girls were being raised by the Warnocks. He'd asked God to find a good home for his daughters, and God had done exactly that.

"It made me feel good, how they were participating in church," Vernon said.

Vernon respected the boundaries set by the Warnocks' adoption of Eve and Lillie, Clay said. "He's not got an agenda to get the girls back."

Explained Vernon: "I'm just trying to get their trust back. This is restoration for them and for me. I want my family to be proud of me. The things I used to do, I don't do no more."

Clay cries when he describes how Eve and Lillie made the traveling basketball team. And he cries when he recalls the night that Daliesha was named Miss Alma High. Daliesha, now 21, lives in Florida and is the mother of a 1-year-old son named Troy.

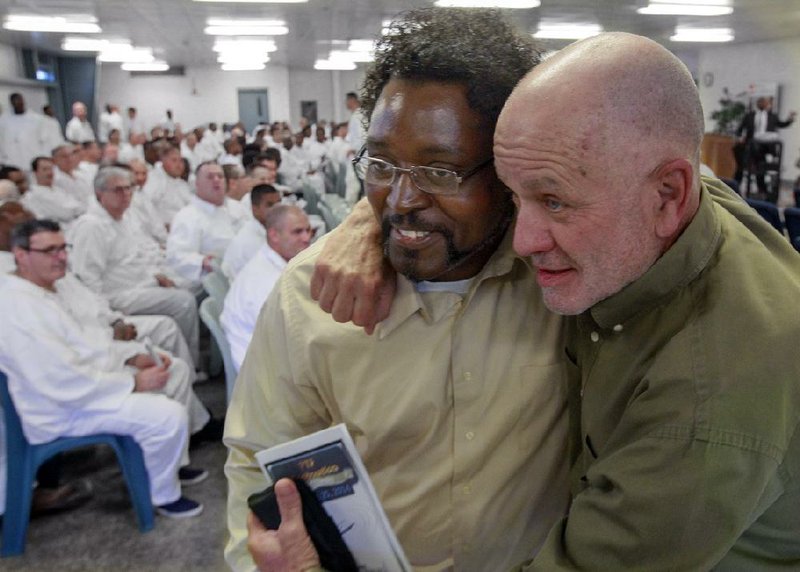

Clay also got a little teary on April 25, when he and Vernon returned to the Wrightsville Unit for the Pathway to Freedom graduation.

This time, Vernon walked through the gates in dress clothes. He grinned broadly while accepting his plaque.

And then the two men embraced -- the adoptive father and the biological father -- who found each other under the most unlikely of circumstances.

SundayMonday on 05/18/2014