THE SUNKEN LANDS

This is the last of four stories about Northeast Arkansas’ Sunken Lands, areas that literally sank during the 1811-1812 New Madrid earthquakes, transforming verdant forests into mosquito-infested swamps.

TODAY: Wilson, a former corporate town, is reborn as its own municipality.

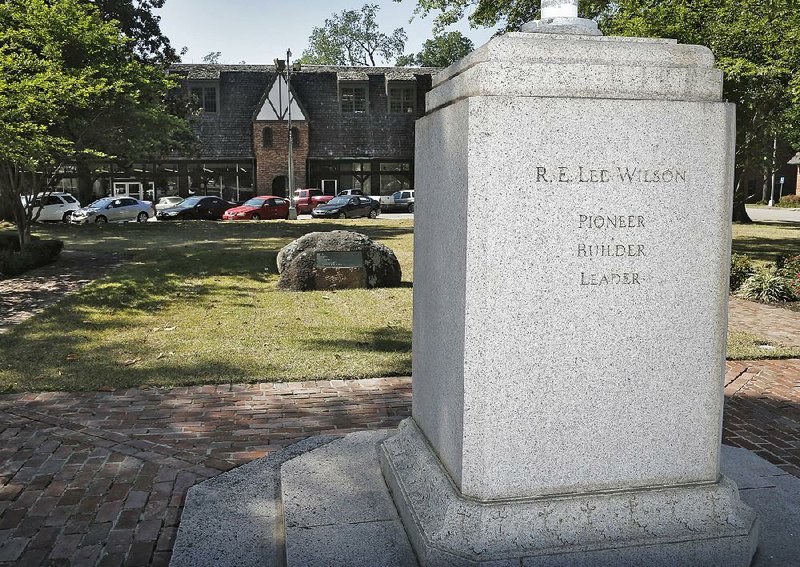

WILSON -- Spend a few days in this Mississippi County town and it will seem you've been here your entire life. You'll be greeted by name as you zigzag across the tiny square or disappear into a sprawling Tudor building encompassing the grocery store, library and city offices, as well as the headquarters of Lee Wilson & Co., the entity to which this Delta town owes its existence.

But spend a few years here and it may seem a lifetime hardly registers. Many of Wilson's 900 inhabitants are rooted five generations deep, and they're wary of change at the behest of outsiders.

In 2010 The Lawrence Group bought Lee Wilson & Co. for more than $100 million, adding it to holdings that included about 150,000 acres of land, banks, citrus groves and the world's largest private air conditioner distributor. The Lawrence Group wanted the company's nearly 30,000 acres, but the purchase also contained the commercial district of a town that apes medieval England. (Generations back, a member of the founding family honeymooned with the Redcoats, catalyzing a town face-lift.)

"At first I was trying to figure out how not to get the town," says Gaylon Lawrence Jr., 51, who heads The Lawrence Group. But after spending time in Wilson, he took a new approach.

"You start thinking, what can we do with it?"

Lawrence's tone is almost reverential as he speaks of making Wilson a place for agricultural research and home to a private school worthy of shaping the region's bright young minds and, perhaps, his future grandchildren.

“Everywhere that we can have influence, we need to be drawing people in that are knowledgeable,” he says. “The more creators we get here … the bigger mark we make, the quicker we become sustainable.”

In some ways, Lawrence’s plans echo those of Wilson’s founder, Robert E. Lee Wilson, known as “Boss Lee.” Wilson pioneered drainage and flood control, taming Mississippi River swamps into farms. In 1918 he hired a professor to teach his employees business and science. Six years later, he built a state-ofthe-art trade school for black students, to complement the academic school attended by children of his white employees.

In the beginning, Wilson was a company town, and all structures were company property. The Bank of Wilson existed largely to provide capital for the company. During the Depression, employees were paid with company currency, which limited their purchases to company retailers. When the town incorporated in 1959, elderly residents say they hardly noticed.

The company retained commercial property, but sold employees the houses they had been renting — some for decades — and began to receive county monies for infrastructure. A Wilson always ran for mayor unopposed, and town patriarchs still arbitrated civil and criminal disputes.

“This was Complaint City, USA,” says Boss Lee Wilson’s great-grandson, Steve Wilson, 66, from the dark-paneled office he used to occupy. “That might be anything from spousal abuse to dogs digging up flowers. … People didn’t know anybody to go to anywhere else.”

Billy Joe McAfee, 76, worked at the company equipment plant. He remembers when the public school needed a bus. Steve’s father, Robert “Bobby” E. Lee Wilson IV, asked McAfee to buy two and send him the bill. In the early 1980s when a Saturday at the Wilson Tavern got out of hand, Bobby Wilson cut off alcohol indefinitely — the company held the liquor license.

REVAMPING WILSON

“We don’t own the city … we own property inside the city limits,” says Steve Wilson. He was the last Wilson remaining at Lee Wilson & Co. when he retired in December. “Rural income for buildings is not near enough to maintain them. So it was our insistence that anybody who looked at buying the land would take all the assets.”

Lawrence is no stranger to farming towns. His parents grew up near Pollard, Ark., and he was born just over the border, in Poplar Bluff, Mo. His father, Gaylon Lawrence Sr., grew the The Lawrence Group from a small farm that was bought with the backing of his own father’s mortgaged land.

Lawrence’s father died in 2012, and Lawrence moved The Lawrence Group’s headquarters to Wilson. He commutes from Memphis each day, but his son Drew, 24, resides in Wilson full time, overseeing the farms. “We’re trying to stimulate the town where eventually it will be self-sustaining,” Lawrence says. “That really is all about giving people the ideas and the ability and the beginning.”

Under the guidance of John Faulkner, a prep-school teacher Lawrence hired as town planner in July, Wilson’s only sit-down restaurant reopened; the square was sodded, repainted and set up with Wi-Fi, and the town water supply was flushed. Land has been leveled for a community garden, a monthly concert series is underway and Faulkner hounded communications companies into repositioning towers, improving cellular service.

He also oversaw plans for a new facility for the Hampson Museum, an archaeological collection owned by the state but housed in Wilson. Groundbreaking is slated for August and the project, like the restaurant, proposed school and garden, has received funds from The Lawrence Group.

Locals gush about new conveniences, but lament what they say is a lack of information. Linda Bridges has been town pharmacist since 1986. She doesn’t know why there’s construction next door, behind the Wilson Cafe.

“We’re assuming it’s a parking lot,” she says, because parking gets tight at the square on the two nights the cafe stays open for dinner. Joe Cartwright, who runs the cafe, says the space will be a picnic/event area.

According to councilman Justin Cissell, 35, he and 34-year-old Becton Bell, a fifth-generation farmer and mayor of Wilson, are working “to bridge that gap” between locals and newcomers.

“We’ve been waiting for an opportunity like this, and we’re truly blessed and grateful, but we just want people to realize that we didn’t give up on Wilson,” Cissell says. “When they talk about how Gaylon’s going to save the town because it’s his dream … it’s my dream, it’s others who’ve lived in this town for years. But when you don’t have the money to back you, people won’t even talk to you.”

The city has no employees and contracts Lee Wilson & Co. to handle trash, water, sewer and maintenance. Otto Warhurst, city clerk and former mayor (in 2008, he became the first mayor who didn’t share the town’s name), is paid by the company. Faulkner, 59, says he’s the “only full-time person who thinks about the problems continually. That’s why Gaylon hired me, because he didn’t want the town and the town’s problems to always be on the side of the desk for everyone.”

The four-member city council meets in the company boardroom and receives a small stipend from county taxes, which also fund the volunteer fire department.

“Over the years, if a council person decided they didn’t want to be on here anymore, they would still run and probably be unopposed, and then they would resign and the council would appoint who they wanted,” Bell says.

According to the Arkansas Municipal League, this kind of situation is unusual but not illegal.

When Warhurst stepped down as mayor, Bell was appointed by the council. To keep the office, he’ll have to run for election in November. He says when Warhurst retires at the end of the year, the city plans to hire and fund its own clerk.

ARKANSAS’ MAYBERRY

“If you’ve grown up here, you’re pretty much with everybody else. You can go to somebody’s front door, just show up at their house and they’re OK with it,” says Kelsie Wilson, 17, president of the senior class at Rivercrest High School and no relation to the town’s founding family.

She plans to attend Arkansas State University at Jonesboro and settle in Wilson, where violent crime is non-existent, where people walk to the grocery store and church and where, on crisp Friday nights, most of the town heads to a field called Cotton Patch to celebrate high school football.

“People back trucks up to the fence and get fires going. … It gets crazy out there,” she says. Bell is proud that Wilson has fewer boarded buildings than many small towns.

“The Wilson family … left the town in pristine condition. It was like you went back in time 50 years,” Bell says.

But Sam Yankaway remembers what Wilson was like 50 years ago, and he wouldn’t trade today.

“This town has improved 100 percent since I first come up,” he says.

Yankaway, 75, was born to tenant farmers who worked Wilson land. His family of 11 lived in four rooms, where “it was raining in on you, snowing in on you.”

But he felt safe in Wilson. “It used to be high racial, but Wilson, he was the town boss and the mayor … if a riot come up, he would stop it,” Yankaway says.

Wilson remains segregated. Most white residents live behind the town square; most black residents live across the railroad tracks in a neighborhood dominated by a public housing complex.

A BLANK PAGE

Bryant Whitted, 40, is pastor of Greater Macedonia Missionary Baptist Church. His congregation has grown from 30 to 100 since moving eight years ago from the outskirts of town. The church was founded by field hands over a century ago; most of its members work at the American Greetings Corp. in Osceola, 14 miles north, or make knock-off Kool-Aid and other products at Wilson’s Gilster-Mary Lee Corp.

“The church owns a block. We basically sit on the corner of a new neighborhood when it springs up. That’s what they said when they showed me the town plans,” says Whitted, who negotiated the land with the Wilsons. But for now, the lots around the church remain empty, affording a spectacular sunset view.

According to Bell, there’s not a single house on the market. “Mr. Lawrence owns all the land in a circle around Wilson, so if there’s going to be any development, he has to do it.”

Big River Steel, LLC plans to build a billion-dollar mill in Osceola next year. If Wilson is to benefit, it needs more housing. Faulkner says a subdivision will be developed in an area he touts as “a natural arboretum,” with nearly two dozen tree species.

People are hesitant to speak on record, since many are tenants or employees of Lawrence’s. But they complain about clusters of forest being cleared and a pecan grove that was razed. They worry that newcomers will transform the culture of the town.

Tess Pruett runs the Hampson Museum. “I’m hoping the growth … will bring, more than anything, tourists that will come see what we have and then go back home,” she says. To Bridges, Wilson isn’t about the Wilson family or Gaylon Lawrence.

“The people are always going to be genuine and sincere. Even if you want to make them cultured and artsy, they may accept some of that, but they’re still going to be basic, honest, Bible-belt people.”

Locals take complaints to Steve Wilson, but he tells them his hands are tied. He wasn’t thrilled to sell, but his family’s younger generation had little interest in agriculture or managing a town.

“There’s nothing here that’s sacrosanct, other than that grave out there,” he says. A rock in the center of the square marks Boss Lee’s final resting place. Steve Wilson has a house in town, but spends a lot of time in Memphis with his wife, daughter and grandchildren. The town is an epistle from his forefathers, wood and brick inked in deeds glorious and shameful, the cottonwoods and stranded cypresses rustling with stories epic and tiny.

For Lawrence, Wilson is something else.

“When you have to change everything and catch back up, that’s twice as much work as starting with a clean sheet of paper … Wilson is the closest thing to a clean sheet of paper that there is, with something already here.”

Keep up with Wilson happenings on Facebook, at facebook.com/ WilsonArkansas.

Style on 05/25/2014