SHAW AIR FORCE BASE, S.C. -- The United States is shifting more attack and surveillance aircraft from Afghanistan to the air war against the Islamic State extremist group, deepening U.S. involvement in the conflict and raising new challenges for the military planners who work in central South Carolina, far from the targets they will pick for those aircraft.

A dozen A-10 ground-attack planes have recently moved from Afghanistan to Kuwait, where they are to start flying missions supporting Iraqi ground troops as early as this week, military officials said. About half a dozen missile-firing Reaper drones also will be redeployed from Afghanistan in the next several weeks.

Perhaps nowhere outside the Middle East do the additional aircraft have a more direct effect than at Shaw Air Force Base, which has become a leading symbol of the military's ability to carry out global operations from afar.

But while the Air Force personnel who help plan strikes against the Islamic State from South Carolina will have more firepower to bring to bear, they face an unusual enemy -- a hybrid between a conventional army and a terrorist network that has not proved to be an easy target for American air power.

"When we target a nation-state, we've typically been looking at their capability for decades and have extensive target sets," said Maj. Sonny Alberdeston, the targeting chief at Shaw Air Force Base. "But these guys are moving around. They can be in one place, and then a week later, they're gone."

Just as the Pentagon flies its wartime fleet of Predator and Reaper drones from bases in Nevada and elsewhere across the United States, the rear headquarters of Central Command's air forces carries out the bulk of the work to analyze and select planned, or deliberate, targets that allied warplanes strike in Syria and Iraq.

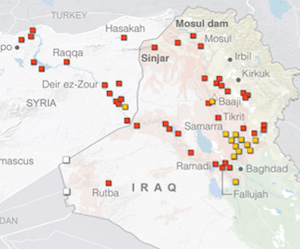

The targets are fixed sites such as military headquarters and communications centers, oil refineries, training camps, troop barracks and weapons depots -- in short, everything the Islamic State needs to sustain its fight.

More than 7,000 miles away at Al Udeid Air Base in Qatar, in the Persian Gulf, another group of analysts and targeting specialists focuses on so-called pop-up targets -- convoys of militants or heavy weaponry on the move.

These have been the top priority of the three-month campaign, even though only about one out of every four aircraft missions sent to attack them has dropped its bombs.

The rest of the missions have returned to the base, failing to find a target they were permitted to hit under the strict rules of engagement designed to avoid civilian casualties.

Of the 450 strikes in Syria through last week, about 25 percent were planned, military officials said. Of the 540 strikes in Iraq through the same period, there were even fewer -- only 5 percent of the total.

Critics complain that the air campaign is flagging against an adaptive enemy.

"We need to have more targeting capability than they have right now," said Sen. James Inhofe of Oklahoma, the senior Republican on the Armed Services Committee, who recently returned from Jordan, where several countries are using a base to fly combat missions against the Islamic State.

Every afternoon in South Carolina, Col. Scott Murray, the senior intelligence officer at the base and a veteran of earlier air campaigns in Iraq, Afghanistan and Kosovo, convenes his top staff members to review targets: just completed, about to happen and future strikes.

Some targets are automatically off-limits, such as dams, schools and hospitals. Several dozen come with restrictions, like rules that say they can be attacked only at night, when presumably no people are around. At any given time, there are fewer than 100 targets on the list that have been approved to be hit.

Planners at Al Udeid work down that list, matching up specific aircraft and specific weapons best suited to destroy or disable a target with minimum risk to civilians, officials said.

Working at computers in cubicles in nondescript offices, analysts examine lists of suggested targets or other "points of interest" offered by the CIA, U.S. military intelligence agencies, allied spy organizations or Iraqi forces.

The analysts check to see if the targets are legitimate, fit the priorities of Gen. Lloyd J. Austin III, the head of Central Command, and can be struck without risking civilian casualties. They use sophisticated computer programs to determine which weapon and which approach to the target will cause the least risk to civilians.

Human-rights groups concur that the U.S. military has taken steps to reduce the risk of civilian casualties in the air campaign but said the dangers would increase when allied-backed Iraqi ground forces seek to retake cities such Mosul.

"When they're actually fighting in urban areas, the challenges will be harder to make sure they're not causing harm," said Federico Borello, the executive director of the Center for Civilians in Conflict, an advocacy group. "The U.S. and coalition forces will need to have processes in place to investigate and respond to any allegations of civilian casualties."

A Section on 11/28/2014