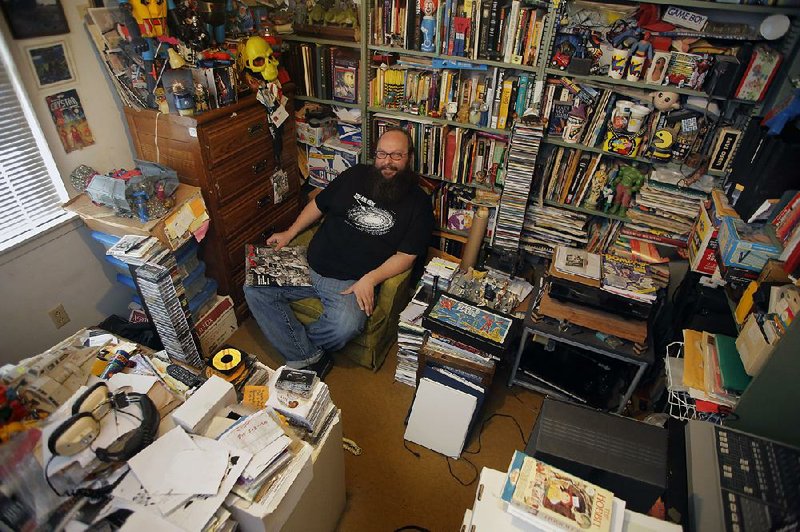

Harold Ott's childhood bedroom in Jacksonville is a curious place. It's small and square, the walls lined with industrial shelves laden with decades worth of video-game consoles, 30-year-old toys and boxes of old 45s.

Neat piles of oddities encroach upon floor space, crowding the only furniture in the room: a shrunken olive armchair, circa early '70s, and an elaborate turntable setup (a wooden brace on brass footers, on a metal shelf on brass footers, all of it designed to shoot playing vibrations to the floor).

This is where Ott, who is not a small man, sits in a small chair and listens to small records.

Listening to records is an important part of Ott's job. It's not the job he's paid to do. That would be making prints and ensuring things run smoothly at Bedford Camera's North Little Rock store, where he has been a steady presence for the past 12 years. This other business, operated out of a quirkily transformed rectangle of first-generation suburbia, the business that eats up countless after-work hours belonging to him, to his girlfriend Dakota Norsworthy, and to his sister Rachel Ott, is more unique and arguably more important.

That's because Ott is in the business of cultural preservation.

THE LOST SOULS

In 1999, when Ott was just back from studying communications at the University of Arkansas at Fayetteville, he attended a Butler Center for Arkansas Studies showcase of state-based garage bands and bought the accompanying compilation, The Little Rock Sound, 1965-69.

Six years later he bought another garage rock compilation, No No No, put out by Massachusetts-based Arf! Arf! Records. The liner notes included the songs' original 45 RPM labels and Ott noticed that one of the bands, Lost Souls, was from Jacksonville. The band hadn't made it onto the Butler Center compilation.

Ott asked around. He went to Jacksonville Guitar, in operation since 1975, and asked if anyone had heard of the Lost Souls.

Owner Steve Evans sent him to Doug Fritz at Fritz Electronics. Fritz had a phone number for Lost Souls singer/guitarist Mike Petray.

"He was kind of excited to be talking about a record he made 40 years ago, so I decided, well, maybe we should just film an interview with him ... it led to, well, let's try to find the other guys in the band," Ott says. "And this was the basis for the movie."

In 2005, Ott shot an hour-long documentary. It's essentially three of the four Lost Souls waxing nostalgic:

"We played at every Dairy Queen in town that summer," Petray says. "We tried to be as polished as we knew how."

("Polished" consisted of Mike Corbin buying a real bass, rather than playing the top four strings of a six-string guitar, and the guys adopting matching uniforms and synchronized dance moves.) They played enough skating rinks, youth centers and Air Force clubs to buy their girlfriends frequent dinners at Roy Fisher's Steak House.

"We had enough money to do that, man, we thought we was doing great," Corbin says.

PSYCH OF THE SOUTH

Ott started looking for other long-ago Arkansas bands. Bill Eginton, 61, the owner of the Arkansas Record & CD Exchange in North Little Rock, loaned Ott 45s. He found some records through estate sales or garage forums and online sites such as eBay. Sometimes he got records from former band members.

"The same things people use to stalk people online, I use to find old musicians," Ott says. He often pays for searches on whitepages.com, peoplefinder.com and classmates.com.

"Classmates is really handy because they posted all these yearbooks .... Most of these bands are in high school," he says. Some of them were younger. Ott found one group, Electric Sunshine, that was made up of Jonesboro fourth-graders.

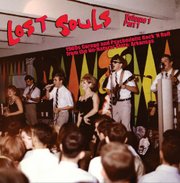

In 2007, Ott put together Lost Souls, Volume 1: 1960s Garage and Psychedelic Rock 'n' Roll From the Un-Natural State, a 29-song compilation, released on his own Psych of the South label. But there were unforeseen challenges.

Firstly, there was the legal problem of figuring out who had the authority to release these songs. Sometimes Ott didn't even know the names of band members. "The studio owner owns master rights, usually, but if the song wasn't published, it's in murky territory. And a lot of this was not published," Ott says. "What usually happens is, someone just says I'll put my name on it, it's close enough, and you pray."

Ott would be more worried if Psych of the South turns a profit. It doesn't. Even so, he faced competition.

"I said [on the online forums], 'Hey, I know about the Lost Souls'... And when I did that, a guy from England wrote me and was like, yeah, you know, I've been doing each state ... So they basically went ahead and put out an Arkansas compilation, right after I said that," Ott says.

The bloke was Max Waller, who works with a 17-year-old Florida label called Gear Fab Records on a Psychedelic States collection. It covers 13 states thus far.

"It was a roadblock for me because I'd already put together a list of stuff I was going to put out, and most of it was on their CD. So I kind of had to start from scratch," Ott says. "I just hunkered down and dug deeper."

BEHIND THE MAN

Many people are surprised when they meet Ott. They expect him to be two decades older than his 39 years. They expect his obsession to be fueled by personal reminiscence. But Ott's teenage soundtrack went something like this: Metallica, Megadeth, Iron Maiden, Anthrax, Slayer.

"If you were a rebellious teen in Jacksonville, it was metal," he says.

He started playing guitar at 14, spurred by his friend William ''Rocky'' Gray. The future drummer of Evanescence would come over and play Ott's mother's acoustic.

Ott has been in several bands -- the grunge-saturated Lollygadget, the hard rocking Kill Switch and most recently, the synthesizer-heavy Exit Human. He remembers the Little Rock punk scene of the '80s and '90s, immortalized in the documentary Towncraft.

"We'd go down by the river [today's River Market], they'd have that 50-gallon bucket burning for your heat and light, and they'd just plug into city power and play ... but there was segregation between the punks [Little Rock] and the metal kids [north of the river] .... We mixed in a little, but we had our own thing," he says.

He discovered underground garage in the early '90s, when he bought the compilation Back From the Grave, Volume 4.

"You've got a band in the mid-'60s putting out a record. There's one side that they think may play on the radio, so that was a little tamed down ... and on the other side they just did whatever they wanted," he says. "It's whatever they wanted where they sometimes hit that nerve, that sounds like punk from the '70s, a good 10, 12 years early."

BEHIND THE MUSIC

Ott's favorite local garage track, "Don't Send Me No Flowers," is a cover of a Memphis band, The Breakers, recorded in Batesville by The Blue & the Gray. Wolfgang Volkel, with the German Break-a-way Records (Psych's biggest distributor), and Mike Dugo of 60sgarageband.com count it among their top tracks.

It opens with a simple beat, before tambourine jangle and bratty vocals kick in. In the liner notes, Ott calls it "a slab of primordial garage-punk." He hasn't been able to figure out who was in The Blue & the Gray or even where they were from. What he does know, or at least suspects, is that only two original copies of this track exist, and he can locate both of them.

"One was over at Bill's house in one of his boxes. The second record, a buddy of mine, he used to live in Batesville and work at the radio station where George Whitaker [owner of Zay-Dee Records] operated out of. He had one of those records in a shed that was getting rained in," Ott says.

Probably the most valuable record he owns is by a Little Rock group called Federal Union.

"They played very few live shows but it became legendary, because this hardcore collector, Barry Wickham, he put out this book a few years ago and talked about this Federal Union acetate ... just a killer punk track, and they were going to hoard it, and you're never going to hear it," Ott says.

Ott convinced Wickham to let him borrow the acetate (a record not intended for repeat plays) to release "Can't Stop, Can't Go" and its B-side,"I Really Need You."

A second California collector, Joey Dryka, answered a classified ad to dig through crates in a Sacramento garage. He found two more Federal Union acetates, with a different version of "Can't Stop, Can't Go," and with another song, "A Day Without Time." He sold one copy to Ott and the other to an Australian named Mark Taylor, one of the top collectors in the world. The latter went for $1,500. All four recordings landed on the fourth and latest volume in the Lost Souls series, released in May 2013.

In addition to the compilations, Psych of the South offers records -- an EP and a few singles -- with help from Break-a-way and two American distributors. Ott finds the songs, writes liner notes and designs packages, and his affiliated labels press the records and send Ott a share to sell.

"Basically I do all the work and they pay for it," Ott says.

He supports Psych of the South through freelance transfers from reel-to-reel tapes, a task that gobbles a portion of most evenings. Altogether he has sold about 1,200 CDs. Almost all the buyers are from outside Arkansas.

"It even goes back to the blues guys, same with rockabilly and soul .... There's just more appreciation for historic music in Europe," Ott says.

BEHIND THE SOUND

Volkel and Dugo like The Problem of Tyme's "Back of My Mind" (Lost Souls, Volume 1), which Volkel describes as "folk-garage with great vocals" and Dugo calls "a Byrds-like track with jangling, ringing guitars."

Additionally, Volkel digs "the Barefacts, Yardleys, Lost Souls and especially The Coachmen." He calls the latter "snotty Stones/Kinks-style '60s-punk."

"Nothing was original," says Tom Roberts, 66, a semiretired dentist who plays with the band Kavanaugh and played rhythm guitar for The Coachmen. "One song, we tried to make it sound like we were a Stax soul group and there were others where we tried to emulate English ballad-type songs."

The Coachmen's "You're My Girl" (Volume 1) features a cool, punchy rhythm, R&B vocals and a psychedelic guitar break. They played frat parties and proms in Memphis and Arkansas, and their stage show featured go-go dancers.

Eginton and Rachel Ott like the Lost Souls' "Lost Love," a dreamy tune with surf undertones and a bluesy break. But Eginton didn't discover the song through Ott. He found the original record at a flea market 20 years ago and later realized that the singer was Fil Griggs, his longtime barber.

David Grace, 63, a Little Rock lawyer, has lent a few records to the Lost Souls compilations. As a teenager in El Dorado, Grace played horns in garage bands that never recorded. But another band from his hometown, Mystical Illusion, has a funky keyboard song called "Colour of My Daye" on Volume 1.

Grace prefers "Your Love Is Gone" by the Trouble Brothers (Volume 1), and "Tired of Working for the Other Man" by Danny Johnson and The Rhythm Makers (Volume 3).

"The Trouble Brothers were a complete, astonishing revelation .... They don't sound like anybody else," he says. The song is uptempo, employing tinny guitar percussion. It sounds a bit like a psychedelic take on mariachi.

Grace describes "Tired of Working for the Other Man" as "a rockabilly-ish type record .... It's kind of political ... about a guy expressing his desire to get out from under the thumb of some employer and be treated fairly and do his own thing."

According to Roberts, in the '60s it seemed everyone was in a band. "We had Stax over in Memphis ... you had Detroit and Motown and Philly, the British, the Beatles and in America, the Beach Boys. Music was really diverse and rich, and you know, not everybody wanted to play football," he says.

For Eginton, garage music is about universal themes and unique sounds: "They each had their own heartbreak song or their own I-met-this-girl song."

"It's amateur, in the best sense of the word," Grace says. "It's people who are doing it because they like it, and they're trying to learn how to do it, and they're inspired by something, as opposed to doing it for a calculated reason such as making money. It's more direct and immediate."

Information: psychofthesouth.com.

Style on 11/30/2014