Turner Grain Merchandising is far from alone in defending itself from lawsuits in the storm that has shaken the $3.7 billion grain industry in Arkansas.

Three lawsuits name the Brinkley-based company as one of 15 Arkansas firms.

The suits seek a total of $14 million. Farmers and others in the grain industry say they have not been paid for their crops. The whereabouts of their grain is unknown, the plaintiffs say.

Other lawsuits are expected. The lawyer for six Mississippi farmers, who had not filed suit by Friday afternoon, contends Turner Grain Merchandising received corn from them valued at $1.7 million.

State agriculture officials have voiced fears that losses could go well beyond $15.7 million. Secretary of Agriculture Butch Calhoun said the total could range from $20 million to $50 million.

In Arkansas, grain dealers are not regulated by the state. They do not need licenses, and they are not required to be bonded. Dealers buy grain from a producer and sell it to a third party.

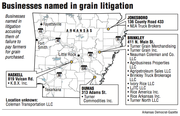

The suit filed in Lonoke County Circuit Court on behalf of rice farmers lists an address for 11 of the 15 companies as 411 North Main St. in Brinkley, a 1,200-square-foot building with a red brick facade. The lawsuit says that is the address of the headquarters for Turner Grain Merchandising, Turner Grain Inc., Neauman Coleman and Co. LLC, Agribusiness Properties LLC, Agripetroleum Sales LLC, Brinkley Truck Brokerage LLC, Ivory Rice LLC, LJTC LLC, Rice America Inc., Rice Arkansas Inc. and Turner North LLC.

The Lonoke suit also names as defendants Turner Commodities Inc. in Dumas, K.B.X. Inc. in Saline County; NEA Truck Brokers in Jonesboro, and Coleman Transportation LLC, location unknown.

A suit filed in Lee County for eight farmers names nine of those companies. One filed in Monroe County for two grain processors in Louisiana names two of them.

The nature of the relationships among the businesses is not clear, but three of the four individuals who have been sued in the complaints have roles in more than one of them.

Turner Grain Merchandising was formed in 2002, with Dale Bartlett as president and Jason Coleman as vice president and secretary, according to the Arkansas secretary of state's website.

Jason Coleman is the registered agent for Agribusiness Properties, a grain storage facility near Brinkley that was established in 2004, according to the website.

Coleman was a "principal" in Neauman Coleman and Co. LLC until he resigned Aug. 19, according to records at the National Futures Association, a self-regulatory group. A principal in this instance meant that he owned at least 10 percent of the company. Bartlett, another principal, resigned the same day. Neauman Coleman, Jason Coleman's uncle, owns Neauman Coleman and Co.

Jason Coleman and Bartlett were deeply involved in the running of Dumas-based Turner Commodities Inc., according to testimony by its president, Gerald Loyd. Loyd testified in a hearing related to a suit in Lee County Circuit Court against him and Turner Commodities that its operations -- including record keeping, money and grain -- were mixed with those of Turner Grain Merchandising.

Turner Commodities' website says that Loyd is owner and president. There is no mention of Coleman or Bartlett. There is no record of its incorporation on the Arkansas secretary of state's office website.

The Lonoke County Circuit Court lawsuit also lists four men -- Bartlett, Jason Coleman, Neauman Coleman and Christopher Taylor, who is assigned no role in the suit, but who signed contracts for Turner Grain Inc., according to Lonoke County plaintiffs' attorney Don Campbell of Little Rock.

Instead of "separate and distinct corporations, partnerships and limited liability companies," they are just stand-ins for those four men, the Lonoke County suit contends.

Turner Grain Merchandising is tiny compared with the grain-trading giants such as Bunge and Archer Daniels Midland.

A complex alliance of so many firms with the relatively small Brinkley grain dealer "at a minimum raises some red flags about why there are that many," said Susan Schneider, director of the Agricultural and Food Law degree program at the University of Arkansas School of Law in Fayetteville.

There can be legitimate business reasons for that number, Schneider said, but it lends itself to obscuring the "accountability ... for the funding structure," Schneider said.

Responses from defendants are incomplete and trial dates have not been set for the cases.

Thirty-five states require licenses and bonding for grain dealers. In 1991, a bill in the Arkansas Legislature to provide for licensing and bonding of grain dealers died after a hostile amendment was introduced in a House committee, despite unanimous passage in the Senate.

The Arkansas Legislature is to take up the issue again in January.

Some of the companies named as defendants have a name common to them, Turner, which may raise the question: who is that?

It's not a person. It's a place, not even a village, in western Phillips County that has a sentimental value to Bartlett and Jason Coleman, according to Loyd. Yet the crossroads in a sea of cropland has a name today that has far transcended its origins.

The negative impact on a $20 million default would be $10.5 million on the state's economy, especially in the eastern Arkansas counties where the grain was produced, according to a researcher at the University of Arkansas at Little Rock.

Schneider applauded efforts by the U.S. Department of Agriculture and Arkansas' congressional delegation to give farmers affected by the Turner Grain collapse more time to pay back federal crop loans.

Schneider, who said she has been involved in agricultural law in one capacity or another for 25 years, advised the state of Ohio on setting up a law to provide protection for farmers in financial collapses of large grain elevator operations, which were common in the Midwest in the late '80s and early '90s.

She cited grain operation shutdowns in other states. But those cases were fairly straightforward -- either a bankruptcy or voluntary shutdown of an elevator operation -- with the grain in hand.

By contrast, Agribusiness Properties, the grain storage facility near Brinkley, was shut down Aug. 14 when USDA agents found no grain in the elevators despite certificates on the premises saying there was.

Storage facilities in Arkansas are regulated by the State Plant Board or the USDA. The federal agency set a 20-cents-per bushel bonding limit for grain in storage at the 241,000-bushel Agribusiness Properties elevators used by Turner Grain -- in other words, 0nly a small fraction of the value of the grain.

A grain elevator in Pierce, Neb., shut down in March, still holding unsold soybeans and corn. Two hundred and 12 farmers filed claims of $9.7 million.

The Nebraska Public Service Commission ruled Sept. 3 that farmers with legitimate claims on unsold grain would get $4.8 million. Farmers whose grain had already been sold but hadn't been paid had to fend for themselves, according to John Fecht, director of the commission's Grain Department.

A storage facility is one thing, but all a grain dealer needs in Arkansas is "an office, a computer and a pickup," as Calhoun, the state's agriculture secretary, put it.

Which can make a dealer hard to find in some cases.

The suit filed in Lonoke County on behalf of rice growers named among the defendants K.B.X. Inc., which had bought the rice from Turner Grain, according to supporting documents.

The scant website for K.B.X. lists its address as 819 Vulcan Road in Haskell, a town in Saline County. The phone number is answered with a K.B.X. greeting.

But that is the address for Rineco Chemicals Enterprises. Rineco converts hazardous waste into fuel, and, according to its website, has been at the address since 1986.

One of the owners of Rineco is Steven Keith, according to its permit issued by the Arkansas Department of Environmental Quality. He is also listed as president of K.B.X., according to the secretary of state's office website. He is not named in the farmers' suit as an individual defendant.

Ernest Harper, attorney for K.B.X. and Rineco, said that while K.B.X. is headquartered on the Rineco property, "K.B.X. and Rineco have nothing to do with each other. They have totally different business plans, totally different business operations. Rineco is a recycling company and K.B.X. deals with agricultural commodities."

Thus far, there has been no corporate bankruptcy filing in the Turner Grain episode.

Bartlett has filed a petition in U.S. Bankruptcy Court for Eastern Arkansas for individual protection under Chapter 12 as a farmer.

Bartlett's Sept. 5 petition lists liabilities and assets, each in a range between $1 million and $10 million. He got an extension until Monday to file the particulars of his case.

SundayMonday Business on 10/05/2014