As head of the Arkansas Economic Development Commission, Grant Tennille logs about 20,000 miles traveling the state each year.

Those trips often take Tennille to Northwest Arkansas, which has been a standout in the state and nation for its economic growth. But no matter how many times Tennille travels into Benton and Washington counties, he said, it always feels a bit foreign.

"I'm like most people, and I'm up there a lot, but I still drive through the tunnel and feel like I've entered a completely different world," Tennille said. "It doesn't feel like the rest of Arkansas. Not in any bad way or good way. It's just different."

For the past 15 years, the Bobby Hopper Tunnel on Interstate 49 has provided a tangible, brick and concrete, dividing line between Northwest Arkansas and the rest of the state. With its hills, proximity to the borders of Oklahoma and Missouri, and a feel that is more Midwestern than Southern, there can be a noticeable disconnect between the region and portions of the state that exist south and east of the Washington County line.

Tension between central and Northwest Arkansas, currently the state's largest and most thriving economic regions, has existed for decades. Often the friction bubbles just below the surface, occasionally making its way to the top in battles as major as the Civil War or in less life-and-death skirmishes like the ever-present debate over where the University of Arkansas plays its Razorbacks football games. Even the university itself has served as the center of a fight between two regions that historically have been at odds politically, geographically and economically.

Warwick Sabin, director of the Arkansas Regional Innovation Hub and a state representative, moved to Arkansas from New York when he was 17 to attend the University of Arkansas. He eventually landed in Little Rock, and as an outsider who came of age in the state, he said there is little doubt a friction exists, sometimes to the detriment of the state's fewer than 3 million residents.

"It's definitely real, and it needs to be overcome," Sabin said. "I definitely acknowledge that. It's easier to overcome once everybody lets their guard down and has a long-term vision instead of trying to secure short-term wins."

Regional Snapshot

While the two may compete for bragging rights over job creation or cultural amenities, they both have clearly established places within the state's economy. They each fill their own niches, often with little overlap between them.

Both regions -- defined for the purposes of this article as the Little Rock-North Little Rock-Conway and Fayetteville-Rogers-Springdale metropolitan statistical areas -- have their own personalities and strengths.

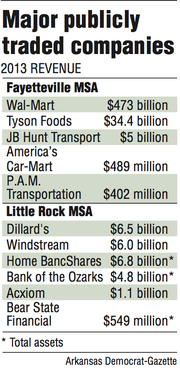

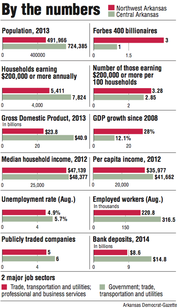

Home to three Fortune 500 companies and five major publicly traded companies, Northwest Arkansas has experienced rapid economic growth, especially since 2008, as its gross domestic product -- the measure of the value of services and finished goods produced -- has grown 28 percent. For 2013, the GDP was $23.8 billion.

Unemployment in Northwest Arkansas is less than 4.9 percent, and for every 100 households, 3.28 are earning more than $200,000 annually. Among its 491,966 residents are three of Forbes' 400 billionaires, Johnelle Hunt (J.B. Hunt Transportation Services Inc.) and Rob and Jim Walton (Wal-Mart Stores Inc.).

"It's hard to say something about Northwest Arkansas that hasn't been said, but it's an impressive track record," said Greg Kaza, executive director of the Arkansas Policy Foundation.

Still, there are areas where the region lags behind its big brother to the south. Little Rock, established as the state's capital in 1836, has a significant head start.

Little Rock's metropolitan statistical area has fewer Forbes billionaires among its 724,385 residents -- Warren Stephens (Stephens Inc.) is the only one -- but there are more residents earning $200,000 annually with 7,824. Little Rock also leads the way in major publicly traded companies with six, although it has a 5.7 percent unemployment rate. Still, the central Arkansas region has a lower unemployment rate than many of its peer regions throughout the country and the national average of 5.9 percent.

A look at the two major employment sectors provides a more detailed snapshot of the differences between the two. Little Rock and its metropolitan statistical area, a six-county collection of towns, thrive on the strength of government and health care support and information technology-focused employers like Acxiom Corp. and Windstream Corp.

Government, education and health care make up about 35 percent of the central Arkansas workforce. That number is 24 percent in Northwest Arkansas, where the strength lies in trade, transportation and utilities, employing about 22 percent of the workforce, thanks to Wal-Mart, J.B. Hunt and Tyson Foods Inc. Little Rock's workforce in the sector is about 19 percent.

Leaders in both regions are working to expand their economies, but their strengths will remain just as they are now for the foreseeable future. Little Rock is no more likely to become a retail hub than Northwest Arkansas is to become a destination for health care.

"Major changes to employment sectors aren't made on a dime," said Kathy Deck, head of the Center for Business and Economic Research at the University of Arkansas. "There is a great challenge for all regions to foster the industries that you have, while not being so dependent on them that if something happens, the whole economy tanks. ... Economic developers everywhere want to diversify their portfolios. They all have limited resources, so there is tension between further clusters of growth you have to try and diversify and make riskier bets on economic sectors you might not have a strength in."

Detailed Differences

Even the emerging startup scenes in central and Northwest Arkansas highlight the differences between the regions.

Take, for example, the work being done in data analytics. Entrepreneurs at startups in both regions are working to find solutions for harnessing "big data," but innovations in Northwest Arkansas tend to focus on retail and logistics. These are the sectors that are major strengths for the economy. Little Rock, on the other hand, is seeing startup growth in areas of finance, government and health care services.

Tennille notes a similar dividing line in how data analytics will be taught in the state's two- and four-year schools. Those differences, though, make Arkansas more attractive for companies looking to relocate.

"There is already talk outside the state and among academics that if you need big data solutions, Arkansas is a place to go," Tennille said. "Those jobs just take on different forms whether they're in central Arkansas or Northwest Arkansas."

Collaboration, not competition, will be key to substantial and sustainable growth in the regions going forward, he said.

It is no coincidence that the rise of Northwest Arkansas has occurred as local leaders began taking a more regional approach. Instead of assigning its major airport to one city, the conscious decision was made to name it the Northwest Arkansas Regional Airport. A similar philosophy led to the minor league baseball team in Springdale being named the Northwest Arkansas Naturals and not being town-specific.

Professor Jay Barth, who teaches political science at Hendrix College in Conway, said that in recent times the municipalities in Northwest Arkansas have done a better job of planning and acting in concert, mostly due to lessons learned in the boom times. Little Rock and the communities that surround it have grown at a more steady pace over a longer period and, as a result, have developed more independently of one another. The result is less cooperation.

"There is no doubt that central Arkansas has to use regional solutions to more of its challenges," Barth said.

Competition Isn't Bad

Those on the front line of economic development in Little Rock agree. Sabin said the state needs to remember that with fewer than 3 million people, Arkansas as a whole is smaller than many major metropolitan areas.

"It's a very simple concept," Sabin said. "Northwest Arkansas really is leading the way in terms of local leaders building cooperative efforts to increase productivity. We need more of that here. We also need more of that statewide. We are blessed with a diversity of resources across the state, whether it's Northwest Arkansas or central Arkansas or northeast Arkansas and the Delta. We're really shooting ourselves in the foot when we don't work together."

Representatives from the Northwest Arkansas Council and Little Rock's 50 For the Future periodically collaborate. Most recently, the cooperation has included discussions on how to better market the walking and bicycle trail systems in each region that are gaining outside attention.

Less friction seems to exist today, several Little Rock businessmen said.

Bill Holmes, president of the Arkansas Bankers Association, said he can't see a split or perceived rivalry between the two areas. There are now almost 40 different banks located in Benton and Washington counties, Holmes said. Little Rock's metropolitan statistical area has $14.8 billion in bank deposits, compared to $8.6 billion for the Fayetteville area, but there is often overlap.

"So many of the [banks] that are up there are [in central Arkansas], too," said Holmes, whose office is in Little Rock. "I'm sure the [bankers] who started out up there and have been there all the time are wondering when everyone is going to quit coming up to their backyard.

"But day in and day out, I haven't heard anything [about a rivalry] in years, honestly."

John Flake, an owner of Little Rock-based commercial real-estate firm Flake & Kelley Commercial, said the two areas actually are complementary. Flake & Kelley also has an office in Northwest Arkansas. Often when a business locates in either Northwest or central Arkansas, it soon adds an office in the other region, Flake said.

Tennille said he likes to the see collaboration between the two but acknowledged that the differences, when manifested in ways that aren't destructive, can be good for the state.

There might be sniping or accusations of favoritism from one region or the other, but the focus of economic developers in the state is luring businesses who might be considering places like Kansas City, Mo.; Tulsa; Huntsville or Mobile, Ala.; Baton Rouge; or Memphis. Those other cities and states are the real competition, Tennille said. No matter how foreign the regions might feel in comparison, they are still Arkansas. A healthy competition between the two, as well as emerging collaborations, will make the state even more attractive than it already is, he said.

"There is an increasing feeling among citizens of Northwest Arkansas that they are the real economic engine of the state, and they're toting the note for a whole bunch of people," Tennille said. "To some degree that is right, but the real truth is these two MSAs have got to begin to collaborate and understand neither one is toting the note for the whole state. We're doing it together. We've got to work together to ensure both sides grow in a healthy way.

"Locals can push hard to try to distinguish themselves. I'm all for that," he added. "It gives us a better product."

SundayMonday Business on 10/19/2014