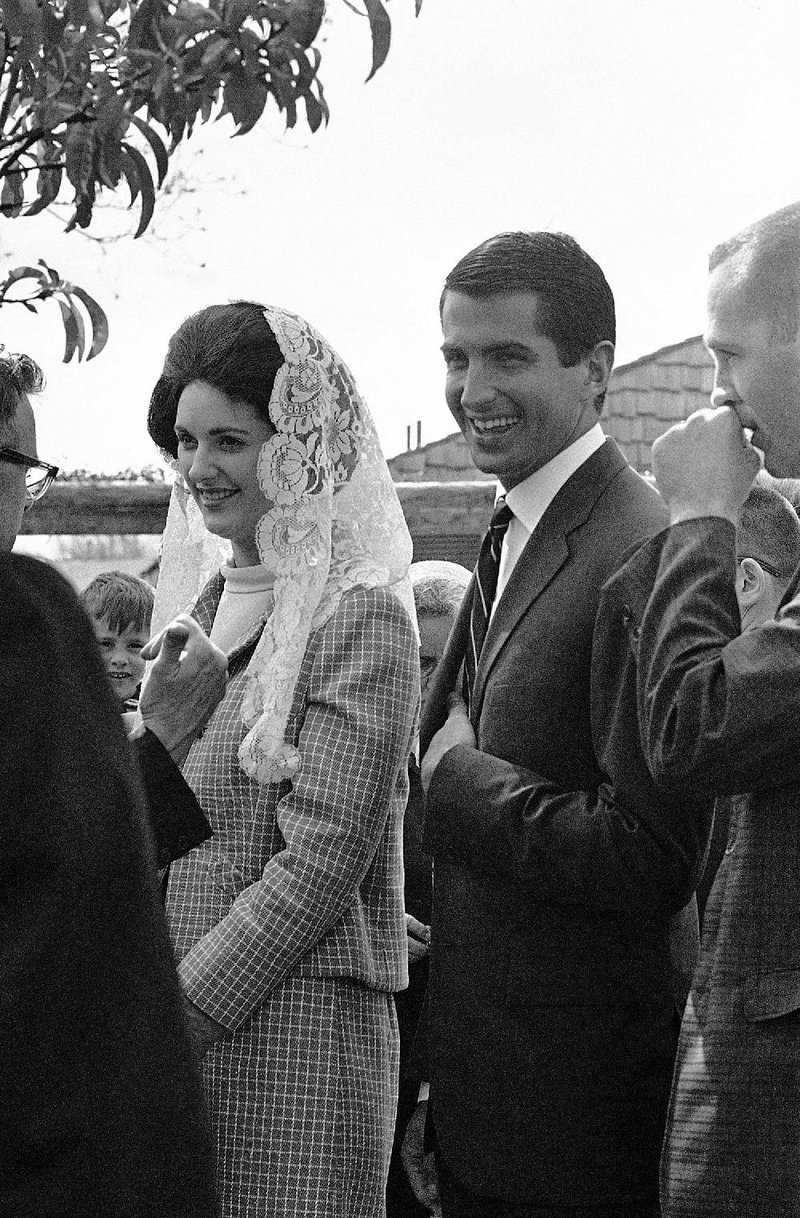

PHILADELPHIA -- For a few months in 1966, the budding romance between film star George Hamilton and Lynda Bird Johnson, daughter of the 36th president, was the talk of Washington.

Gossip columnists followed their every move as Hamilton squired her around town. The couple vacationed in Acapulco and made camera-ready appearances at the Sugar Bowl, Mardi Gras and the Oscars. The actor spent Easter at the LBJ ranch in Texas and even attended the Washington wedding of Lynda's sister, Luci.

President Lyndon Johnson made no secret of his suspicions about the handsome, patent-leather playboy, perhaps best known now for his perpetual tan, blinding smile and roles on TV shows ranging from Columbo to Dynasty to Dancing with the Stars.

But a previously confidential FBI file -- which a Philadelphia judge recently outlined in an opinion and ordered to be released -- shows for the first time how far Johnson went to protect his daughter and his presidency.

The file indicates that Johnson enlisted Supreme Court Justice Abe Fortas and J. Edgar Hoover's FBI to investigate every rumor they could find about Hamilton, including claims that he was gay and a draft dodger, in a bid to dig up dirt on the actor.

In his ruling, U.S. District Judge Eduardo Robreno called it not only an improper probe but also a "potentially illegal use of executive power."

The documents were the focus of a four-year court battle by Villanova Law School professor Tuan Samahon and his students. But they also offer a window into a presidential administration and an FBI that apparently thought little of violating the privacy of American citizens -- an accusation that has resonated for modern presidential administrations.

According to Robreno, who reviewed the controversial file, the documents ended up reflecting most poorly on the FBI itself.

"This case is about the ability of the federal government to pry into the private lives of U.S. citizens with virtual impunity," he wrote in his opinion. "The file can be read as an effort by the FBI to uncover embarrassing details about a private citizen as a personal favor to the president."

The FBI file burnishes a long-established record of the excesses of Hoover's agency and Johnson's willingness to use it to investigate perceived threats. But that wasn't what Samahon, who teaches courses on constitutional law and federal courts, initially went looking for.

He wanted to know what role the FBI may have played in the 1969 resignation of Fortas from the highest court after only four years. Fortas, a Johnson appointee to the court, had been the president's former attorney and longtime confidant.

Samahon filed a Freedom of Information Act request in 2010 to see a memo that he hoped would give him material for a book on Fortas. At the time, he believed it could indicate that the FBI used knowledge of some illicit relationship Fortas had with a man to pressure him into disclosing confidential information about a Supreme Court case.

The Department of Justice released the memo but redacted a single name, saying it could reveal embarrassing details about a private citizen.

Samahon rejected the argument, saying there was no legal reason to keep the name confidential, but the FBI didn't budge. So Samahon put his students to work and in 2012 sued for the documents' release, as well as for the release of the file containing the memo. Samahon said 19 students and Beth Lyon, another Villanova professor, devoted many hours to the case over two years.

The memo Samahon wanted was a two-page report by Cartha DeLoach, deputy director of the FBI and Hoover's right-hand man.

DeLoach, then the third-highest-ranking official in the FBI, had investigated some of the nation's most notorious crimes, including the assassinations of President John F. Kennedy and the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. He was a Hoover loyalist with close ties to Johnson, and many believed he regularly leaked information to the White House about the most salacious FBI investigations.

As the romance blossomed between Hamilton and the president's daughter in early 1966, DeLoach and Fortas were given the uncommon task of sabotaging the relationship. The president, DeLoach wrote in his memoir, also wanted "a full rundown" on Hamilton.

"As far as the president was concerned, Fortas' seat on the Supreme Court didn't preclude him from doing a little moonlighting for the president," DeLoach wrote.

DeLoach and Fortas had a laugh over it, according to DeLoach, then began what DeLoach called a "discreet background check," reviewing the actor's family, friends, credit history, draft deferment and more.

DeLoach became anxious as they failed to turn up anything damaging.

"Every few days I would hustle over to Abe's office in the Supreme Court building," he wrote in his 1995 memoir, Hoover's FBI: The Inside Story by Hoover's Trusted Lieutenant. "He would sweep in, his robes fluttering, and the two of us would pore over the gossip columns and try to think of ways to break up a young couple in love. ... Each day we expected the president to call and chew us out."

When it was clear there was no more to be done, Fortas called to thank DeLoach for his help. DeLoach preserved the conversation in a memo to his boss.

"Justice Fortas called at 10:30 this morning to express appreciation for the information the Director had me furnish him concerning the George Hamilton matter," the memo states. "Justice Fortas advised he agreed with the Director that no further action need be taken at this time."

The memo became part of Hamilton's background-check file, which Robreno described in his Aug. 25 opinion as "pages of gossip." Rumors cited in it ranged from scurrilous to outright false, including the allegation that Lynda Bird Johnson was "running around with a bunch of homosexuals," that Hamilton was a draft dodger, and that the actor was gay and had been seen with someone described as "little more than a prostitute."

In retrospect, the focus on Hamilton's sexual orientation might seem surprising. Outside of his acting career, Hamilton, now 75, is known as a lady-killer with a string of high-profile exes, including Elizabeth Taylor and actress Alana Stewart. He once said, "I don't think anyone in Hollywood has had more dates than me," and in 2008 he made headlines by saying he lost his virginity at age 12 to his own stepmother.

But the Johnson White House of 1966 was gripped by gay paranoia.

Allegations of homosexuality could end careers -- a reality of which the president was uncomfortably aware. In 1964, one of his senior aides, Walter Jenkins, was arrested for allegedly having sex in the men's room of a YMCA. The news leaked on the eve of the presidential election, and Johnson cut Jenkins from his staff to stem the political damage.

Indeed Fortas later confronted claims that he had a dalliance with a male prostitute. In 1967, DeLoach informed Fortas that the prostitute had alleged having a sexual relationship with the justice. Fortas, according to the FBI memo on the incident, denied the allegation and thanked DeLoach for informing him.

DeLoach, who died last year, described Johnson's particular mistrust of Hamilton in his memoir.

"When Lynda Bird became involved with the actor George Hamilton, Johnson became an anxious father," he wrote. "To him, Hamilton seemed no more than a slick opportunist, an upstart taking advantage of his movie fame to charm the daughter of a rich and powerful man."

Hamilton was on vacation and not available for comment, a spokesman said.

But he has acknowledged being aware of those suspicions. It is unclear whether he knew Johnson had enlisted allies on the U.S. Supreme Court and in the nation's top investigative agency to confirm them.

"Gay was the dirtiest word anyone could have used in and around the Johnson White House," Hamilton wrote in his autobiography, Don't Mind If I Do. "As the putative LBJ son-in-law, I was subject to incredible scrutiny."

Federal prosecutors fought the Villanova professor's request for the information for years.

In November 2012, Zane David Memeger, the U.S. attorney in Philadelphia, argued in a filing that releasing the redacted name in the file could stigmatize the person, who had once been the subject of a federal investigation. Concern over privacy, he said, trumped the public's interest.

Memeger's office declined to comment after the judge's ruling last week.

Learning that the redacted name had little to do with his research goal was slightly disappointing, Samahon acknowledged.

"I really don't know why the Obama administration thought this was fit to withhold," he said. "But it's certainly embarrassing that under J. Edgar Hoover, the FBI allowed itself to be used as a personal lackey for the president to run family errands and vet potential sons-in-law. And it's embarrassing that they tried to use privacy interests as a way to hide things that were embarrassing to the agency."

Samahon said he hoped his victory in the case would encourage agencies to comply with open-records laws. The court battle could have been avoided, he said, had the FBI just released the documents and distanced itself from the previous administration. The decision orders the FBI to pay attorneys' fees in the case, which means Samahon's students can prepare an expense report.

"The FBI attorney who decided to withhold this has just cost the agency a lot of money," Samahon said.

SundayMonday on 09/07/2014