The Rev. Ian Paisley, Northern Ireland's firebrand Protestant leader who vowed never to compromise with Irish Catholic nationalists, then, in his twilight, accepted a power-sharing agreement that envisioned a new era of peace after decades of sectarian violence, died Friday in Belfast. He was 88.

Paisley had been fitted with a pacemaker in 2011 after falling ill in London and had retired from politics and the pulpit. His wife, Eileen, confirmed his death in a statement.

The day many thought would never come arrived in Belfast on May 8, 2007. Paisley, founder of the Democratic Unionist party, which sought continued association with Britain, and Martin McGuinness, a Sinn Fein leader and former commander of the Irish Republican Army, which had fought for a united Ireland, took oaths as the leader and deputy leader, respectively, of Northern Ireland's power-sharing government.

As Prime Ministers Tony Blair of Britain and Bertie Ahern of Ireland looked on, the proceedings ended British governance and reinstated home rule in Belfast. It bridged the chasm between Paisley and Gerry Adams, the Sinn Fein leader who had negotiated the agreement. And it relegated to the past civil strife that had raged from the 1960s into the 1990s and cost 3,700 lives.

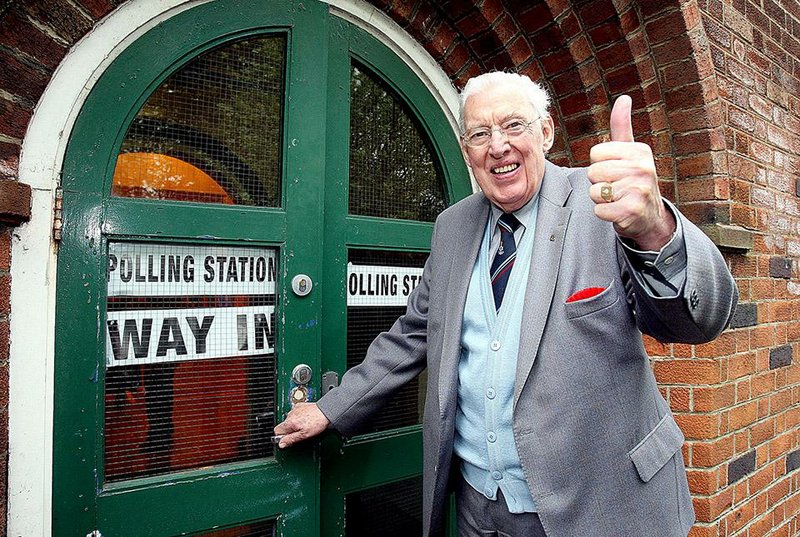

The next year, Paisley -- white-haired, 82 and seemingly mellowed -- resigned as Northern Ireland's first minister and as leader of the Democratic Unionists, by then the dominant party of Protestants in Northern Ireland. He founded the party in 1971.

Paisley had already stepped down as head of the Free Presbyterian Church, which he founded in 1951, and had given up a seat he had held for 28 years in the European Parliament in Strasbourg, France. In 2010 he gave up a seat in the British House of Commons that he had held for 40 years.

It was the winding down of a tumultuous career as a rabble-rousing minister-politician whose single-minded objective had been to preserve Protestant power and repress the Roman Catholic minority, keeping Northern Ireland aligned with Britain, across the Irish Sea, and out of the reach of predominantly Catholic Ireland to the south.

In the 1950s, he organized vigilante patrols to defend Protestant neighborhoods against IRA attacks. Through the following decades of strife -- bombings, assassinations, clashes with British troops, and general strikes and riots he had fomented -- Paisley condemned any deal that might have opened the way to peace or power-sharing with the Catholics, who made up 44 percent of Northern Ireland's nearly 1.8 million people.

John Hume, a Catholic civil-rights leader, once said to Paisley: "Ian, if the word 'no' were to be removed from the English language, you'd be speechless, wouldn't you?"

"No, I wouldn't," Paisley shot back.

While supporters called him a passionate defender of Protestant unionism, some said Paisley's negative stances alienated allies, prolonged violence and held back progress even as prosperity spread in the Irish republic. But Paisley conceded nothing and denied culpability for any violence.

In 1998, a peace agreement was signed by David Trimble, the mainstream Northern Ireland Protestant leader, and Hume, who shared the Nobel Peace Prize that year for their efforts.

The so-called Good Friday Agreement was ratified by voters in Ireland and Northern Ireland. It provided that Ireland could be united only with the consent of Northern Ireland. But it envisioned power sharing, and Paisley opposed it.

By 2007, however, a series of hurdles had been passed: The IRA had destroyed its arsenal of weapons and dismantled its clandestine cells; Sinn Fein had endorsed a reconstituted Northern Ireland police force, which it had long considered an arm of British and Protestant repression; and Paisley had accepted a power-sharing compromise reached at St. Andrews, Scotland.

Ian Richard Kyle Paisley was born on April 6, 1926, in Armagh, Northern Ireland. His father, James, was a Baptist minister; his mother, Isobel, a Scottish evangelist.

Raised in Ballymena, County Antrim, Paisley attended local schools and worked on a farm. He decided to be a minister, studied at a South Wales evangelism school, graduated from Theological Hall of the Reformed Presbyterian Church in Belfast and was ordained in 1946.

But he soon came to believe that his church had deviated from biblical strictures, and he founded the Free Presbyterians, a relatively small fundamentalist sect. The Presbyterian Church, Northern Ireland's largest Protestant denomination, disassociated itself from his anti-Catholic rhetoric for years.

Paisley wrote many volumes of religious and political commentaries, including An Exposition of the Epistle to the Romans (1968), United Ireland -- Never! (1972), America's Debt to Ulster, (1976), No Pope Here, (1982), and The Protestant Reformation (1999).

In 1956, he married Eileen Cassells. The couple had three daughters -- Sharon, Rhonda and Cherith -- and twin sons, Kyle and Ian Jr. They all survive him, as do several grandchildren.

After giving up the seat in the British House of Commons that he had won in 1970, he was succeeded by Ian Jr., and was made a life peer in the House of Lords, known as Baron Bannside of County Antrim. In January 2012, he retired after 65 years as the pastor of Martyrs' Memorial Church in Belfast.

Information for this article was contributed by Douglas Dalby of The New York Times.

A Section on 09/13/2014