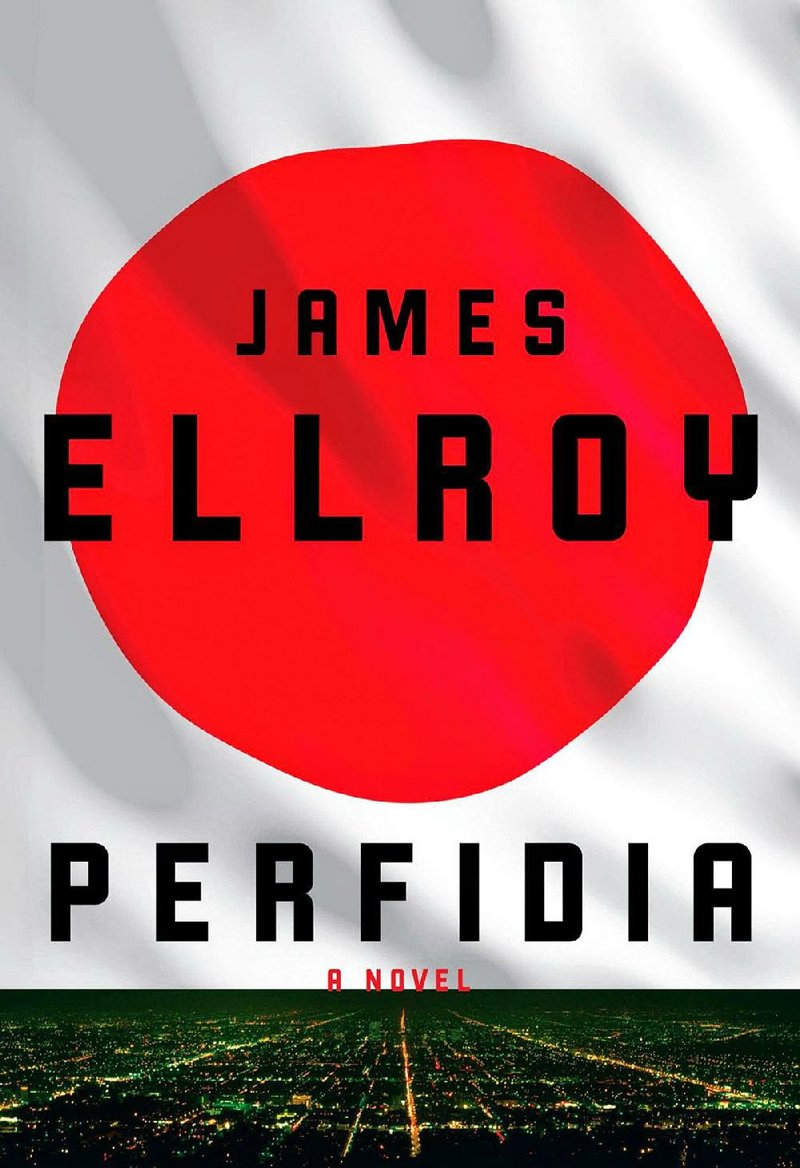

I confess I haven't quite finished reading Perfidia (Knopf, $28.95), Los Angeles-based crime novelist James Ellroy's latest novel and the first in what he says will be a new L.A. Quartet. It is a kind of prequel to the series of novels he wrote from 1987 to 1992 -- The Black Dahlia, The Big Nowhere, L.A. Confidential and White Jazz -- that were set in Los Angeles between 1946 and 1958.

I am a great fan of Ellroy, but my relationship with him is complicated. There have been times I've found his stylized public persona as a hard-boiled hipster -- a "demon dog" -- a bit tedious.

Still, it sells books.

His personal back story is freighted with tragedy. When Ellroy was 10 years old, his mother, who was raising him after she'd divorced his father, was murdered. On a Monday morning in June 1958, Ellroy got out of the cab that was returning him to the El Monte, Calif., bungalow where she lived and walked into a yard swarming with police and newspaper reporters.

"Son, your mother has been killed," a strange man told him. She had been strangled to death with one of her own stockings and dumped in a lover's lane near a local high school. A photographer led the boy into a neighbor's tool shed, handed him an awl and a block of wood. He followed the photographer's instructions -- he stood at a workbench and pretended to saw at the block. A flashbulb popped when he looked at the camera, with something like a weird composure in his dull eyes.

Ellroy has repeatedly insisted that his mother's unsolved murder was the defining event of his life. While others might think it mere self-exploitation, Ellroy has stressed the connections between his life and his art. According to his memoir, it left him with an Oedipal fascination with older women and contributed to a tortured adolescence.

Ellroy spent years scuffling out a marginal existence as a dissipated drug addict, alcoholic and petty thief, and spent a brief period as a neo-Nazi before turning his hand to fiction. He started out writing exquisitely plotted but otherwise unremarkable murder mysteries. When he turned his attention to Los Angeles and, specifically what might be thought of as the secret history of the Los Angeles Police Department from the 1940s through the 1960s, he latched onto a big subject uncontainable by any genre categorization.

Leaving aside the author's tendency for self-sensationalizing, his work is well-observed and profoundly moral. His immense literary universe is complicated, but it is not devoid of honor and spiritual redemption. While his characters are complex and wounded, and their motives ambiguous and often murky even to themselves, there are discernible heroes and villains in Ellroy's books. The good guys are invariably flawed and often the bad guys -- such as the charmingly bent police detective Dudley Smith, who haunts the L.A. Quartet like a patron saint -- are fascinating and thrillingly three-dimensional.

...

In Perfidia, Ellroy jumps back in time to December 1941 to the discovery -- on the eve of the Japanese sneak attack on Pearl Harbor -- of the murder of the Watanabes, a Japanese-American family of four. Whoever killed them arranged the scene to make it look like they committed seppuku (a ritual suicide), but a brilliant police chemist named Hideo Ashida, a Nisei (American-born to Japanese parents) who is the only Japanese-American employed by the Los Angeles Police Department, isn't fooled.

The department, in the midst of rounding up Japanese for internment camps, can use the political cover provided by a genuine investigation of the crime. So the up-and-coming William H. Parker -- one of the real-life historical figures Ellroy seasons his novels with (the real Parker was the longest-serving chief of Los Angeles' police force) -- is assigned to oversee the investigation.

Parker -- "Whiskey Bill," as he's known in the department -- has plenty of his own demons, including "the thirst." But he's also a workaholic and a clean cop, possessed of "superhuman focus and lunatic rectitude."

Parker is riding herd on a pragmatic investigative team led by the charismatic Smith, who's a detective sergeant at this point in his career. Irish-born Smith made his bones as a boy assassin with the Irish Republican Army before emigrating with the help of his mentor, Joseph P. Kennedy. While Smith is a dedicated and talented investigator, he's also a charming sociopath who sees his badge as a license to kill. (He especially enjoys summarily executing "rape-os" -- sexual assault suspects.)

And there's femme fatale Kay Lake, a 21-year-old former prostitute who was rescued by a former boxer turned cop named Lee Blanchard (who loves her, but chastely), who has installed her in an elegant West Hollywood house. Lake (who also figures prominently in The Black Dahlia) is coerced into spying on a communist cell by Parker.

Perfidia continues Ellroy's detailed explication of an alternate history for the Los Angeles police (he expanded his scope in the nationally focused Underworld U.S.A. trilogy, consisting of novels American Tabloid, The Cold Six Thousand and Blood's a Rover, which covered the years 1958 to 1972). But stylistically, Perfidia is somewhat different from his most recent books.

Gone is the telegraphic style that signaled a character's internal monologue. Ellroy has returned to complete and beautifully balanced sentences, which he wields more like a rapier than a dagger. The staccato bursts of American Tabloid have been -- for the most part -- tabled in favor of a more elegant (and to new readers, more scrutable) prose style.

Though Perfidia is unquestionably dark, it's also optimistic. There's heart in this book; we come away liking the characters more than in any of his other work. (So far, at least, I like them -- even when they do dubious things.)

These days, because of the jazzy rhythms of his work, Ellroy is more often compared to Jack Kerouac and the Beats than to genre writers like James M. Cain, Raymond Chandler or Jim Thompson. But I think he's more like Dashiell Hammett in that his cops and robbers live by a code -- they are defined by the work they do. They are all more or less expressions of the Protestant work ethic. Families are subsidiary. Those unconsumed by the gamesmanship of police work are summarily dismissed as incontrovertible squares, civilians, innocent bystanders who might be unlucky enough to catch a stray bullet but otherwise remain at the periphery of the world.

Perfidia may not be the best book Ellroy has written, but it's by far the best place for a curious reader to access his dazzling, crazy worlds. But be careful, there monsters be.

Email:

pmartin@arkansasonline.com

Style on 09/14/2014