Firewood customers are being urged to "buy it where they burn it" after the state Plant Board's decision to impose an emergency quarantine on the movement of all hardwood firewood after the emerald ash borer was detected in six south Arkansas counties.

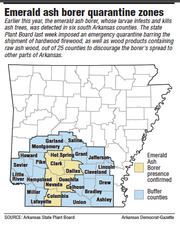

The Plant Board voted to bar hardwood shipments out of a 25-county quarantine area Thursday. Other wood products subject to the quarantine include products directly derived from ash trees including nursery stock, green lumber with the bark still attached, logs, pulpwood, stumps, roots, branches, mulch and compost.

Scott Bray, director of the Plant Board's Plant Industry Division, said the first push will be to educate those involved in the industry -- including loggers, mills, firewood suppliers and plant nurseries -- about the quarantine and the threat posed by the emerald ash borer and how it can affect wood moving both within and out of the quarantine counties.

"As far as firewood, that's going to be the difficult one," Bray said, because there are only a handful of large commercial firewood producers. "The vast, vast majority of firewood moving around the state is just off the radar, and that one is going to be very difficult to regulate. We'll just kind of be looking at it as we can."

Bray said the board plans to work with tree trimmers as well. Even if they don't cut downed trees into firewood, trimmers still must dispose of trees, tops and limbs, and much of that material can fall under the regulations as well.

With outreach as the goal, Bray said: "Let's find them. Let's talk to them. Let's educate them. Let's see what we can work out with them to let them continue business as usual."

The emerald ash borer, a half-inch-long beetle originally from Asia, was first discovered in the U.S. in Michigan in 2002. Since then, it has spread through the Midwest. Its larvae eat into ash trees just behind the bark. An infestation causes the tree to begin to wilt from the top down and can typically kill a tree within two to five years. There is no known treatment that stops infestations.

Max Braswell, executive vice president of the Arkansas Forestry Association, said it's too soon to say what the economic impact of the Plant Board's order will be on loggers.

Even though ash trees make up a small part of the state's forest products industry -- about 2 percent -- it is still a valuable commodity, Braswell said.

The association is helping devise ways to help loggers and processing mills comply with the order, which allows ash to be moved within the quarantined counties.

"The difficulty here is going to be able to identify ash in a load of logs," Braswell said.

The goal will be to minimize the impact of the quarantine on moving wood while slowing the infestation's spread.

Bray said quarantine enforcement will involve methods similar to an existing quarantine on hay shipments imposed to slow the spread of fire ants. While not all loads of hay moving north are inspected, the board does have inspectors who keep a watch out for contaminated loads.

Under the federally imposed fire ant quarantine, agricultural products such as hay, nursery stock or sod grown in more than 30 south and central Arkansas counties can't be shipped into nonquarantine areas to the north without being certified as free of fire ants.

With both the emerald ash borer and fire ant quarantines, the Plant Board has the option of issuing civil penalties of up to $1,000, Bray said. However, he said he was unaware of anyone hit with the maximum penalty for violating the fire ant quarantine.

While ash trees can be a component of hardwood sold for firewood, ash can be used in other wood products. Ash trees are also popular shade trees.

Last month, Plant Board Director Darryl Little alerted the Arkansas Agriculture Board that the borer was a problem in the state. Little said that the borer's impact likely will be more obvious in residential areas where the trees have been planted.

Ash tree losses in urban areas could be "a lot more noticeable than a few trees out in the woods," said Chris Stuhlinger, a forester with the University of Arkansas Division of Agriculture based in Monticello.

Stuhlinger, who said he's planted many ash trees as a forester, said they are popular with urban planners because the tree grows quickly and adapts to a variety of soils and, up to now, was fairly pest resistant.

He said the lack of a significant effort to educate the public about how the borer infests ash trees probably enabled it to slip under the radar into south Arkansas. It has not been detected in the northern half of the state.

"That doesn't mean the borer's not there; it's just not found there yet," he said.

While commercial loggers who work with mills are easier to track, most people who cut firewood or trim trees work independently, making them difficult to contact since there's no central registry.

"A lot of them probably cut out of their backyard or very locally and maybe only sell to a few people. I could see that there might be some cases where firewood gets transported around without it being noticed," Stuhlinger said. "Education is going to be a huge part of this so that both buyers and sellers know what to look out for."

Business on 09/16/2014